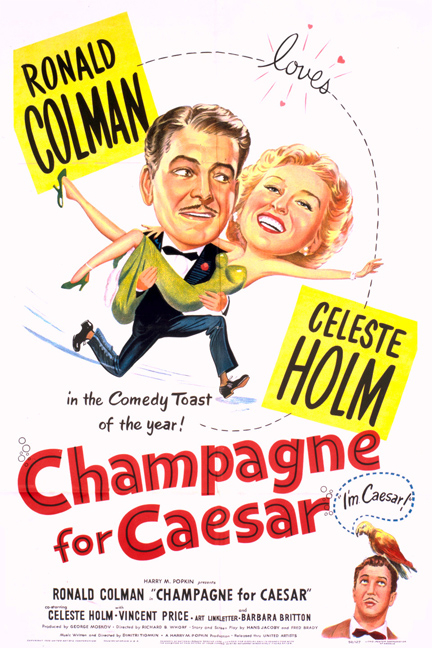

As a teen, I read an old movie review by Pauline Kael, in which she complained that some contemporaneous satirical film was inferior to a similar one made back in 1950, called Champagne for Caesar.

That weird title lodged in my brain; I never stopped scanning TV Guide listings for Champagne for Caesar, and it wasn't until a couple of years ago that I finally saw it.

Which is odd.

Because six years before those infamous quiz show scandals rocked America, Champagne for Caesar not only satirized those popular programs, but used a then-unthinkable "fix" as a cute, plot-resolving punchline (a la Joe E. Lewis' immortal "Well, nobody's perfect" at the end of Some Like It Hot a decade later.)

Not even the success of Robert Redford's Quiz Show in 1994 revived interest in Champagne for Caesar, despite one critic's eloquent effort.

More recently, the Great Glenn Beck Moral Panic (remember that?) produced no end of tedious, tendentious "think pieces" claiming that Beck's rise had been foreshadowed by Network in 1976 (and, once they'd drained that particular metaphorical motherlode, 1957's A Face in the Crowd.)

But despite being the "D-Day crossword" of moviedom's snotty spoofs of the (rival) television industry, Champagne for Caesar was never so much as name-checked.

Barely a handful of us care. And this prescient yet unpretentious little comedy deserves better:

Child prodigy turned middle-aged polymath Beauregard Bottomley (Ronald Colman) is chronically unemployed in spite (or perhaps because) of his pair of PhDs. As he tells the employment office clerk (with whom he's on a first-name basis), "If you know everything, you're not wanted around for long."

That sounds like some Aspergian autodidact's alibi, but besides being a self-described know-it-all, Bottomley is also witty, charming and outgoing; well-mannered and -dressed. (See, "Colman, Robert," above.) This is decidedly not the clumsy, stuttering "intellectual" we're accustomed to seeing in older and more renowned screwball comedies like Bringing Up Baby and Ball of Fire.

So we're left wondering why Bottomley's not an academic or otherwise gainfully occupied: That single unsatisfactory line is all we get — surely somebody could have shoehorned a half-assed "overqualified" into this script — but whatever:

As my late mother always "explained," "But then there'd be no story..."

Bottomley's job hunt takes him to the head office of Milady Soap (which seems to have been decorated by Man Ray in collaboration with Liberace.) He's this close to getting hired, but rubs the neurotic, mercurial company president Burnbridge Waters (Vincent Price, having a marvelous time) the wrong way.

That evening, Bottomley catches a few moments of a silly quiz show called Masquerade for Money, sponsored by... Milady Soap. Bottomley plots his revenge:

As a contestant, he'll easily answer the show's insipid questions, and keep doubling his prize money each week until he racks up $40 million, the precise amount he's calculated he'll need to bankrupt — then take over — Milady Soap...

As produced, written and directed by some guys you've never heard of, Champagne for Caesar is more Frank Tashlin than Preston Sturges, with all that implies in terms of tone, not to mention artisanal precision.

Example: In pretty much every movie starring Bette Davis or Joan Crawford, at least one cast member is obligated to observe that these women (I mean, their characters, their characters!) are devastatingly beautiful. Now, I adore both actresses enough to be accustomed to, and frankly touched by, this insistent screenplay tic. However, something identical yet even less believable mars Champagne for Caesar, except this time the irresistible specimen repeatedly presented for our tacit appreciation is... Art Linkletter.

Now, casting an actual quiz show host as a make-believe quiz show host was, I suppose, a cute, pre-post-modern wink of verisimilitude (think of Richard Dawson's memorable turn in The Running Man decades later), but why insist on presenting potato-faced Linkletter, of all people, as a "dreamboat" forever set-upon by swooning bobby-soxers?

And "What is the Japanese word for 'goodbye'?" couldn't have possibly been considered a "not very easy" quiz question a mere five years after Hiroshima...

Also? The movie's title IS stupid.

So yes, a more talented and ambitious team could have sharpened the satire by smoothing over such speed bumps, but perhaps it's just as well:

I yield to no one in my admiration for Billy Wilder's Ace in the Hole, another satire of mass media mania released just one year later — but the creators of Champagne for Caesar were evidentially uninterested in or incapable of being as "take-no-prisoners" cynical as Wilder, or A Face in the Crowd's Kazan. Hell, the 1955 Gene Kelly musical nothing It's Always Fair Weather takes sharper jabs at the "boob tube" (as it was then-fashionable to describe the cathode ray cancer said to be metastasizing across the nation.)

Refreshingly, Masquerade for Money's viewers aren't moronic grasping suckers; they adore, rather than resent, the brainy Bottomley. (The word "egghead," which we've been lead to believe was a commonplace insult of the era, never appears in this script.)

Furthermore, the likes of J. D. Salinger's tragic "quiz kids" are blessedly absent. (Perhaps, in some pleasant alternative parallel universe, they've been kidnapped and buried alive.)

Nor is it revealed that, oh, I dunno know, Milady Soap is rendered from some noxious "secret" ingredient.

No, Champagne for Caesar is more confectionary than cynical – it's one of the few black and white movies I've ever seen that would have been improved had it been shot in color instead.

Champagne for Caesar is worth seeking out, although not for the reasons its few latter-day fans insist:

This movie isn't really a "look back at a more innocent time" — its double and triple crosses, craven executives and assorted connivers are hardly evidence of a more wholesome era (even if the players are, to our blighted 21st century eyes and ears, impeccably dressed, uniformly slim and disinclined to swearing.)

Many satires aim to not just send up the present, but predict the future. Few succeed as well as Champagne for Caesar, with the added bonus that it's a treat — and not an "eat-your-spinach" chore — to watch. If you can ever find it.