But if you've got these symptoms, you won't last a year:

First, if the pain is kind of heavy. Second, if you can't stop burping unpleasantly.

And your tongue's always dry. You can't get enough water and tea.

And then there's the diarrhea. And, if it isn't diarrhea, well, then you're constipated. Your bowel movements go black.

And then, that meat you used to love so, you can hardly touch it anymore. And whatever you eat, you vomit half an hour later.

And when stuff you ate last week comes up when you vomit, well, then you're done for.

You've hardly got three months...

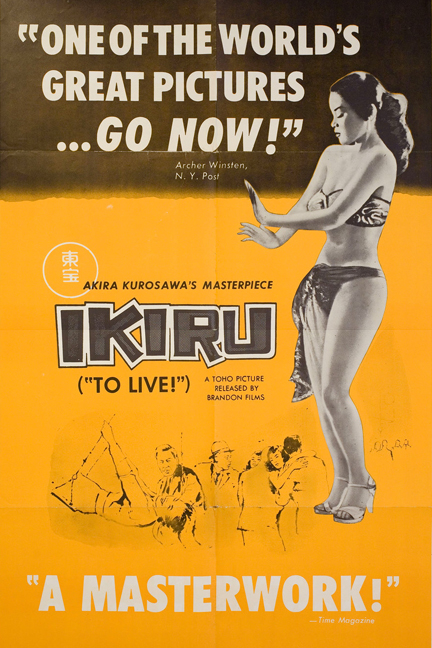

The first shot in Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru (1952) is a blurry x-ray.

A narrator steps up:

This stomach belongs to the protagonist of our story. At this point, our protagonist has no idea he has this cancer.

(Turn on subtitles)

Cinematic narrators often signalling laziness, a lack of confidence —or talent — on the filmmaker's part: Show, don't tell, remember?

But in Ikiru, narration is required: our main character, Mr. Watanabe — the stooped, blank faced public affairs section chief at Tokyo City Hall — is so hollow, he needs some introduction.

Ironically, his hollowness has been reduced somewhat by these growing fatal tumors, the only "lively" new things to come into his life in decades.

The narrator continues:

In fact, this man has been dead for more than 20 years now. He's been worn down completely by the minutia of the bureaucratic machine and the meaningless busyness it breeds.

As Watanabe sits in a doctor's waiting room, he's cornered by a chatty know-it-all who we sense spends a lot of time in these antechambers. He points out another denizen to Watanabe:

That man over there... His doctor told him he's got an ulcer, but trust me, it's stomach cancer. And stomach cancer is practically a death sentence.

The doc usually says it's just a mild ulcer, and that there's no real need to operate. And that you can eat whatever you want as long as it's easy to digest. If that's what he tells you, you've got a year, at most.

Watanabe's doctor gives him that very diagnosis. He's crushed, in shock. His life is over, but also realizes that it really has been "over" for a long time, at least since the death of his wife when his only son was just small. The now grown son and his wife share Watanabe's house, but they are otherwise estranged from the old man. He doesn't tell them what he's learned.

Breaking with his rigid routine, Watanabe goes out drinking and tells a stranger about his condition instead. This rakish writer appoints himself Watanabe's guide through the Tokyo underground of Western style bars and clubs, aiming to teach him how to live for once. But this shabby night on the town leaves Watanabe feeling just as defeated. Their amusements create a vacuum rather than fill it. He can't even enjoy the expensive sake he's splurged on; his stomach can no longer take it.

Watanabe does decide to skip work for the first time in his career, though, pretending to go to the office while aimlessly wandering the city. He bumps into the only bright spark among his fellow office mates, a simple, lively young woman named Toyo who needs his station chief stamp on her resignation papers. Unaware of his condition, she explains that she doesn't want to waste another day at her pointless job. Watanabe becomes obsessed with her, but his interest is hardly romantic: He's mesmerized by her energy and humor, admires her spirit, and wants her "secret" to rub off on him.

This happens, but in an unexpected, roundabout way: Days later, Toyo tells him she loves her new job at the toy factory. Pulling a mechanical bunny out of her purse and setting it hopping across the table, she asks him, "Why don't you try making something too?"

From the start of the film, local mothers have been unsuccessfully campaigning City Hall to have a fetid cesspool turned into a playground. We watch them get directed to different departments, including Watanabe's, being rebuffed at each one.

He has wasted his life at work, but play proved no more meaningful. What if Watanabe can use his work to create play, but for others? He dedicates his final weeks of life to cutting through the bureaucratic clog, clearing the cesspool and putting swings and slides in its place.

None of this happens on screen, though. In a harsh cut, we see Watanabe's photograph on a shrine. "Five months later," our narrator comes back to say, "our protagonist is dead."

We're now at his wake, where incrementally, as drink displaces decorum, family and colleagues try to make sense of Watanabe's curious legacy. What possessed him to single-handedly steer — or more accurately, bully — this little project to completion, at one point even staring down the crime gang that wanted to put up a red light district on the site? It was so unlike him.

One by one, his coworkers remember (or misremember, this isn't clear) his determination, even as his body was failing, to serve the local people for once, his supposed vocation all along.

The sake kicks in. "Let us never forget the spirit of Watanabe," shouts one man. "Let us never forget how we feel at this moment!" All vow to return to City Hall the next day and devote their lives to imitating their late friend's generosity of spirit.

But this is a Kurosawa film, not a Hallmark movie. These men don't realize that it was only because Watanabe was suffering that he was inspired to do what he did, and their morning-after hangovers don't rate. Another's good example will only carry any of us so far. Unless and until they suffer as their friend did, their hearts will probably never change.

Roger Ebert echoes many others when he says that Ikiru "is one of the few movies that might actually be able to inspire someone to lead their life a little differently." But for the reasons above, I can't agree, as much as I'd like to.

That completely contradicts the filmmaker's explicit message at the conclusion, for one thing. For another, it flies in the face of human nature itself, and Kurosawa was a clear-eyed humanist. Like the Russian novelists who so inspired him, he knew that life has no cure.

Let Kathy know what you think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Commenting privileges are among myriad perks reserved exclusively for members of The Mark Steyn Club, alongside exclusive invitations to Steyn events and access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Michele Bachmann, Tal Bachman, Conrad Black and Douglas Murray among Mark's special guests.