I'd never heard of Kenosha, Wisconsin until it turned into an inferno late last month. The city's wholesome, all-American name sounds more like the setting for a mid-century Broadway musical than real-life riots.

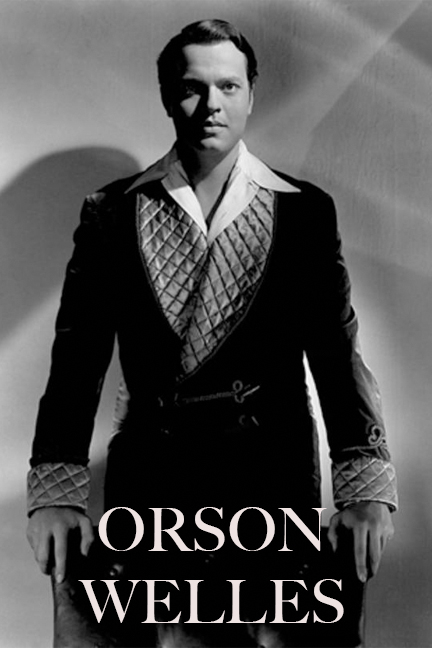

And only last week, I found out it was Orson Welles' hometown. What an incongruous birthplace for such a colossus.

I learned that while watching The Eyes of Orson Welles, an ambitious, if too-earnest, 2018 documentary by film historian Mark Cousins.

"This is Kenosha, where you were born," Cousins 'tells' Welles, whom he's been addressing throughout the film — badgering, really, like a barroom bore (and Cousin's Irish accent adds accidental comedy to that image), poor "Orson" (as he insists upon addressing him) being too dead to tell him to shut up.

We're shown an all too typical American downtown, grey and moss green, its empty streets and stores.

"Now, parts of it look like a deserted Hollywood backlot, or images from the 1930s," the same decade in which his subject rose to precocious fame. Cousins wonders if another Welles will, or even could, somehow emerge from such environs.

Fortunately, this movie was made two years ago and not yesterday, so we're spared any further philosophizing, if one can even call it that. Cousins is probably kicking himself right now, too, because throughout the documentary, he enthuses about Welles' old fashioned (and now extinct) species of "wokeness": Mounting an all-black Macbeth in Harlem in 1936 and such.

So in a version of The Eyes of Orson Welles that blessedly doesn't exist, we'd be forced to hear Cousins ask Welles, "And what did you think, Orson, of the shooting of Jacob Blake in the city in which you were born?"

This is certain because one portion of the film spotlights Welles' now-forgotten efforts to help a black man assaulted by police achieve justice.

In 1946, Welles focused five episodes of his 15-minute radio program Commentaries on what happened to Isaac Woodard:

Having been discharged from active duty in the Pacific that year, this U.S. Army Sergeant was on a Greyhound bus, heading home to South Carolina. Woodard asked the bus to stop for bathroom break. The driver refused. Words were exchanged and, at the next stop, he was removed from the bus by police, including local Chief Lynwood Shull. Still in uniform, Woodard was beaten so severely that he was blinded for life.

Woody Guthrie wrote an even more appalling than usual "ballad" about Isaac Woodard — the lyrics make William McGonagall sound like Philip Larkin — but fortunately he doesn't get to take credit for what happened next: the NAACP said it was Welles' series of broadcasts that catalyzed a Justice Department investigation into the atrocity.

Not surprisingly, an all-white jury acquitted Chief Shull, but it is widely thought that President Truman was so troubled by the case that it helped inspire his decision to desegregate the U.S. military two years later.

Were the Isaac Woodard case still widely remembered, we'd be hearing it compared to Blake's ad nauseum. Because "progressives" live in the past, they persistently insist that each week's latest victim-hero is the reincarnation of Rosa Parks or Emmett Till. In this instance, as in most others, such an analogy would not withstand a moment's sane scrutiny:

Having dutifully and thanklessly served his country, a serviceman barely sets foot on his home soil before becoming another victim of Jim Crow "justice." Contrast that to a compulsive loser in the very same nation — but one that has experienced six decades of progress — getting shot by police after a lifetime of criminal activity.

Yet there is still a case to be made for relevant comparisons to events in our own time.

Nine years after those radio broadcasts, Welles looked back at the case on his BBC Four Sketchbook TV show, and this is the clip Cousins includes in his film. Interestingly, Welles devoted only the first minute or so of this episode to the Woodard outrage, using it as a prompt to talk about policing in general.

Regular visitors to this site, with its "Brit Wanker Copper of the Week" feature, or anyone exposed to the goings on in Australia and Canada, may find Welles' meditations bracing.

An excerpt:

I'm willing to admit that the policeman has a difficult job, a very hard job, but it's the essence of our society that the policeman's job should be hard. He's there to protect, protect the free citizen, not to chase criminals, that's an incidental part of his job. The free citizen is always more of a nuisance to the policeman that the criminal. He knows what to do about the criminal.

I know it's very nice to look out of the window in our comfortable home and see the policeman there protecting our home. We should be grateful for the policeman, but I think we should be grateful, too, for the laws which protect us against the policeman. And there are those laws, you know, and they're quite different from the police regulations. But the regulations do pile up. (...)

We're told that we should cooperate with the authorities. I'm not an anarchist, I don't want to overthrow the rule of law; on the contrary, I want to bring the policeman to law.

While Orson Welles merely starred in The Third Man (1949), he's credited with contributing the screenplay's most famous lines, which also happen to concern law and order.

I'd be lying if I claimed that I didn't find this little speech stirring. We artists tend to be ruthless types, who scaffold our pseudo-sophistication with suchlike sweeping statements praising creative destruction; William Falkner was simply more candid than most: "The 'Ode to a Grecian Urn' is worth any number of little old ladies."

Note, however:

The Swiss never made cuckoo clocks; in the time of the Borgias, Switzerland possessed "the most powerful and feared military force in Europe." And Welles' character, Harry Lime, is the film's glib, heartless villain, selling precious medicine meant for refugee children on the black market to the highest bidder.

So there's all that.

While watching COPS over the years, I was never able to settle on whom to side with: the criminals, or the police. Neither made it easy to choose.

"These aren't my pants" is a catchphrase around our house because not once but three times on that program, we've heard suspects explain away the presence of drugs and weapons on their person with that dubious claim; meanwhile, the police onscreen robotically rattle off, "What I'm gonna need for you to do for me right now sir is to go ahead and" carry out a rapid-fire series of contradictory physical movements at Taser point.

Now we aren't allowed to watch the show at all, of course.

I invite everyone to make of all this what they will, perhaps joining me in wondering if anything good will come out of Kenosha.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with Kathy and your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Michele Bachmann among Mark's special guests.