After 2018's Mark Steyn Cruise docked at its final stop, Arnie and I stayed a few extra days in Boston.

We took a Freedom Trail walking tour, guided by an actor costumed as a real life 18th century local. (When I got home, I sent a thank you note to our exceptional guide, Gabriel Graetz, via Facebook — a note that was even more enthusiastic after I read a few of his posts and realized he was a man of the VERY far left. Yet not once did he express his political views during the tour, which I appreciated. Thanks again, Gabriel!)

Before we began the tour, we introduced ourselves. Arnie and I were the only Canadians. Occasionally, Gabriel would gently quiz us on early American history. I'd look around, pause a second or two, then answer. Correctly.

"How do YOU know that?" an American in our group finally asked.

Well, it helped that I was 12 years old during the bicentennial, when TV was wall to wall red, white and blue history. (Raise your hand if you remember The Adams Chronicles.) I can still sing all these songs.

But otherwise, like most Canadians, I was steeped in reflexive anti-Americanism. Only after 9/11 did I go out of my way to learn that many of the horrible things I'd been told all my life about the United States of America (from liberal US sources, not just the CBC) simply weren't true.

I read books about the American Revolution, entranced by that almost Biblical saga – especially compared to pokey Canadian history. Attempts to make ours more exciting have birthed mortifying, forced-march efforts like "Heritage Minutes," which prod us to thrill to the tales of Some Girl Who Ran Through the Forest, The Airplane That Fell In the Water, and — take THAT, America: We half-invented Superman!

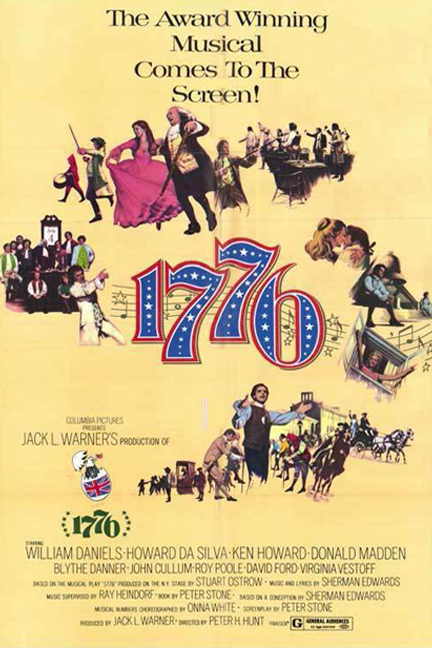

When we finally got TCM up here, I got to participate in the annual American tradition of watching 1776 on July 4.

A musical about the Continental Congress trying to pass the Declaration of Independence was considered doomed to fail when it made it to Broadway in 1969 — wasn't Hair playing right down the street? Surely America wasn't in the mood for a traditional production about the dead white guys in foppish outfits who'd midwifed the very nation that many of its own citizens were currently burning down and blowing up.

Sherman Edwards had been told that, or something like it, for as long as he'd labored over his passion project. We often hear that 1776 was "written by a history teacher," conjuring images of an unknown loner (maybe a bit of a crank, who lived in the middle of nowhere) who somehow managed to get a play produced on the Great White Way.

I could never quite wrap my head around that either until I learned that Edwards had also been a Brill Building composer. He co-wrote the lovely "See You In September" and that catchy feminist bête noire, "Johnny Get Angry":

Johnny get mad

Give me the biggest lecture I ever had

I want a brave man, I want a cave man

Don't blame him for those lyrics, though, ladies — they're Hal David's. But the lyrics, as well as the music, for 1776 is all Edwards, because, after working on the music for six years, he still couldn't find a willing librettist.

Oscar-winning screenwriter Peter Stone (Charade, Father Goose) wrote the book, but didn't want to at first. Like everybody else, Stone thought "1776 sounded like maybe the worst idea that had ever been proposed for a musical."

Then he met up with Edwards, who:

... made a beeline for the piano. "[In] a rotten singing voice," Stone recalled, Sherman "sang 'Sit Down, John.' And the minute I heard that, I knew I wanted to do it. Because in that song is the entire fabric and level of the show: You are involved with people whom we'd never dealt with before, except as cardboard figures. This room had flies, it was hot, and these men were not perfect. There's more information about the Continental Congress in that opening song than I learned in all my years at school."

That's William Daniels reprising his (almost Tony-winning) Broadway role as John Adams. Ken Howard plays Thomas Jefferson, and Howard Da Silva almost steals the movie as Benjamin Franklin. My favorite performance, though, is Ralston Hall's, also reprising his Broadway role as Secretary of the Continental Congress, Charles Thomson, who reads aloud General Washington's increasingly depressing letters from the field.

Peter Hunt ended up directing the 1972 film adaptation. It wasn't a pleasant experience. Irascible, obtuse and philistine studio head Jack Warner had purchased the movie rights, but no one could figure out why.

He didn't like what he perceived to be the show's politics, and argued for changes to this line or that one. Hunt usually won these battles, or so he thought: When he saw the finished film, he realized that Warner had cut the lines anyway behind his back.

And not just lines, either. According to some reports, President Richard Nixon (who'd earlier had the musical staged at the White House, itself a tale that's the stuff of legend: "The last time Da Silva had received an invitation from Nixon, it was to testify before 1947's House Committee on Un-American Activities...") persuaded Warner to excise the song "Cool, Cool Considerate Men." Fortunately, the song was restored on the 1992 laserdisc, and in every subsequent DVD version.

That wasn't Hunt and Warner's only battle:

Hunt wanted to preview 1776 in San Francisco, but Warner objected, saying the town had "too many Jews and too many gentiles." This didn't make much sense, either, until Hunt realized that what Warner wanted to avoid were experts on the subject who might throw too much light on the film's factual errors.

And it's true that, particularly on the topic of who did or didn't support slavery at the time, 1776 takes, er, liberties: Franklin is presented as the founder of an abolitionist society, which he was, but not at that time.

However, the musical is true to the spirit of history, and much of the dialogue comes from the Founders' own words.

Why am I writing about this movie now, a week after Independence Day? Because another award-winning musical about the Founding Fathers is in the news:

"Hamilton getting cancelled after being the nexus of 2015-2016 in-group liberal culture will be utterly hilarious," tweeted Noam Blum on July 4, to which someone replied:

"You're forgetting the best part. Right as it becomes accessible to people who aren't rich and in an ivory tower."

With great fanfare, Disney+ started airing a TV production of Lin-Manuel Miranda's widely acclaimed hip-hop musical Hamilton last week.

How could that go wrong?

Well, the usual human toothaches rose to denounce the same musical they'd all hailed as revolutionary and "woke" a mere five years ago. Now, they say, Hamilton is "problematic," a "text" that must be "interrogated" for its "unconscious racism" and "valorization of the patriarchy."

#CancelHamilton trended on Twitter.

And not for the first and last time in this century, we were treated to the spectacle of conservatives rushing to defend something that liberals had loudly championed within living memory.

That most conservatives turned up their noses at Miranda's inter-racial rap show when it debuted — because "Obama" or whatever — is something that, as the kids say these days, I'll just leave right here.

Interestingly, and inevitably, when Hamilton was still The Greatest Thing In the History of Ever, Miranda was asked what he thought about 1776.

He praised the book as "one of the best, if not the best, ever written for musical theatre."

1776 "paved the way for Hamilton, he said, by presenting the Founding Fathers are flawed, flesh and blood individuals:

"I think it makes them accessible to us in a very real way. To begin an opening number with everyone telling another guy to shut up—what better way to pull these people that we see on statues and on our currency off of the pedestal?"

Ah, yes.

Telling a guy to shut up.

Statues and pedestals.

It all rings a bell.

And Liberty has nothing to do with it.

While we had to postpone this year's cruise to next year, it's sure to be a great time on the Mediterranean with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Michele Bachmann among Mark's special guests. Book yourself a stateroom here. To join in on the collegiality year round, consider joining The Mark Steyn Club, a global community of Mark Steyn readers and listeners.