I was in elementary school when the edict came down:

Everyone Must Learn French NOW Or Canada Will Fall Apart!

From what I could make out, if the Rest of Canada didn't become bilingual immediately, the province of Quebec would keep kidnapping people and blowing up mailboxes. Or, apparently worse, "separate."

Even back then, I resented being ordered around by the government.

So I refused to learn French, which was obviously a stupid language anyway since (judging from the fine print on my cereal boxes) it took twice as many words to say the same stuff. Same with the other new thing: metric, which is (not coincidentally I'm sure) also French. I only passed years of mandatory French classes by a nose, and to this day refuse to use Celsius and kilometers.

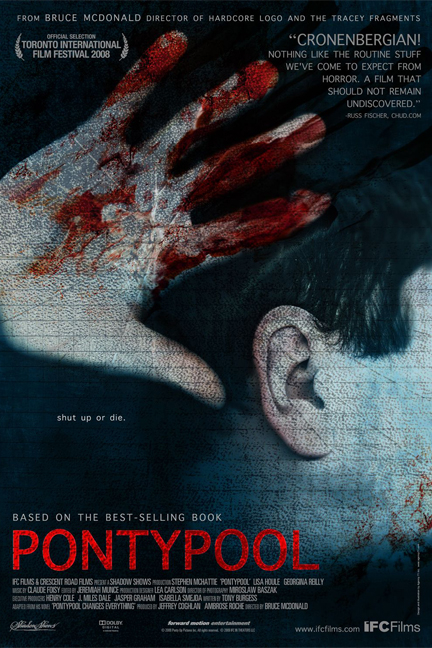

Pontypool is a Canadian film directed by Bruce McDonald and based on Tony Burgess' novel Pontypool Changes Everything. It's a zombie film, but with a cerebral twist. Whereas other movies in this sub-genre regurgitate the canonic creature-killing mantra, "Aim for their brains," Pontypool aims at yours.

Aging shock jock Grant Mazzy (played by Stephen McHattie, whose face and voice perform half of the film's heavy lifting) has recently been reduced to hosting a morning show in the movie's titular Ontario town, broadcasting from a three-person station in a drab church basement.

It's a dark, cold, snowy Valentine's Day, and Grant — who bears what I presume is an intentional resemblance to Don Imus — is bristling at having to drone into the mic about school closings and a missing cat named Honey.

Mazzy dutifully checks in with Ken Loney up in the station's "Sunshine Chopper," but instead of giving his usual boring traffic rundown, Loney reports that a mob has surrounded a local doctor's office. As he watches –– and Mazzy and his crew listen –– the scene descends into mayhem; townsfolk, Loney reports, are assaulting the building, and each other, while making bizarre sounds.

When his producer reveals to Mazzy that the "Sunshine Chopper" doesn't exist — that it's really just Ken in his old car, perched on a hill overlooking the town's few roads — he (and we) start to wonder what else is (and isn't) real. Mazzy's determined to find out, by staying on the air and taking calls from an increasingly chaotic outside world.

So far, so normal, at least in terms of zombie movie tropes:

A cadre of characters trapped in a confined space, surrounded by marauders infected by a "virus," trying to make sense of what's happening and working out what they can do about it.

If that also sounds a lot like your life under quarantine, well, I've noticed a lot of zombie-themed movies (including Pontypool) being broadcast on TV lately (while, hilariously, production of my only "appointment viewing" TV program, The Walking Dead, was halted earlier this year because of... COVID-19.)

It's occurred to me recently — how could it not? — that many more movies are about viruses than I'd imagined, and not all of them in the horror or sci-fi genres. Just today, without even trying, I stumbled upon this synopsis of the 1968 "hip replacement" offering, What's So Bad About Feeling Good?

"...a highly contagious virus (...) quickly spreads across New York City making the normal irritable and rude locals extremely happy, polite and filled with euphoria. In other words, by NYC standards, they have become 'sick.'"

But the Pontypool virus is even more original.

It's spread, not by bites and bacteria, but by words. Specifically, the English language, and, even more specifically, terms of endearment.

Now, lashon hara, the Jewish notion of corrosive "evil speech," such as gossip and rumours, is an ancient one, and not unexplored in movies like A Letter To Three Wives (1949.) And we've all heard altogether too much about the alleged real-life menace of "hate speech."

But in Pontypool, "love speech" is the vector.

The idea that "language is a virus" was popularized by William S. Burroughs almost half a century ago, but actually dates back further.

Plagues, and the "word of mouth" misinformation that inevitably spreads along with them, have a fascinating pedigree in English literature; a copy of Neal Stephenson's language-as-virus cult sci-fi novel Snow Crash is a visual Easter egg in the Pontypool radio station. And didn't Van Jones just assert that all white people had a racist "virus in his or her brain that can be activated at an instant"?

(Astonishingly, as I was writing that sentence, a friend emailed me this news story:

"French speakers should say 'vous' to each other rather than 'tu' and avoid colourful French insults, to avoid spraying out spit droplets that could contain the Covid-19 virus, linguists say."

So there's a lot to think about if one is, like me, so inclined. Fittingly for a film about language, people who like talking about Pontypool really, really like talking about Pontypool. Threads like this one abound, and here's one popular theory:

"The virus evolved from the dialogue Mazzy gave over the radio, as heard in the opening credits of the movie, and as shown visually as 'typo' becomes 'Pontypool.' Mazzy is the source and the vector – who spread it over the radio to the local community."

Some viewers, pointing to Pontypool's Valentine's Day setting, suggest that expressions of love have become so cheapened — we name cats "Honey," and say "I love my fridge" — that the film's virus is a cosmic warning to stop using such words so promiscuously.

But why English?

I feel safe in presuming that the filmmakers' politics lean left; perhaps making the English language the invisible villain is a murky metaphor for British and American "imperialism" (as if the French weren't colonizers too.) Frankly, given the movie's Canadian setting, a far more coherent plot would have seen the French language spreading uncontrollably and destructively across the nation.

As allegory, Pontypool's French/English conceit makes as little sense as the highly vaunted District 9's: Guys, the "alien invaders" in South African history were the whites, not the blacks.

Sadly, Pontypool doesn't develop its promising satirical premise — that empty jargon, and a media ecosystem that's at turns tedious and toxic, are driving humans to destroy each other — to its full potential.

Pontypool feels like it either has one scene too few, or one too many. (And if that sounds pompous and presumptuous coming from non-filmmaker me, let me double down and say that I feel the same way about The Godfather.)

Anyhow: When the doctor whose office was destroyed by that morning mob squeezes through the radio station window to "explain" the language virus — in the manner of white-coated scientists in 1950s creature features — he doesn't explain it very well. (Although given the movie's theme, that may be part of the point.) McDonald could have replaced that bit with additional scenes of our trapped trio groping to puzzle it out by themselves, a la John Carpenter's The Thing or The Fog, two films from which Pontypool clearly takes some inspiration.

So is Pontypool just another "Worthwhile Canadian Initiative"? With a tweak here and there, it could have been a classic; its core ideas are ingenious, the performances are great, and I admit to being haunted by the movie days after watching it, even the second time around.

And yet...

While I'm normally nauseated by the very thought of remakes, I'd love to see an American director give Pontypool a spin. Maybe repair the pacing problems and ramp up the tension even more.

Of course, they'd have to throw out all the French stuff, but hey, that's what I've been dreaming of my whole life anyhow.

Let Kathy know what think of this review in the comments. If you want to join in on the conversation, consider joining the Mark Steyn Club. From access to exclusive Club events to discounts to SteynStore products to commenting privileges, there are perks for all in the Mark Steyn Club.