Re-watching Terms of Endearment (1983) while having cancer may have been one of the dumber things I've done recently. (Or not. I can't decide.)

(One of the smartest, on the other hand, was resuming too-long-deferred funeral planning just in case, and getting my marble tombstone engraved GET OFF MY LAWN.)

I hadn't watched Terms of Endearment since I saw it in a theater during its first run, along with what seemed like every third person in North America: It eventually grossed over $100 million, an impressive sum for a movie without androids or AH-nold.

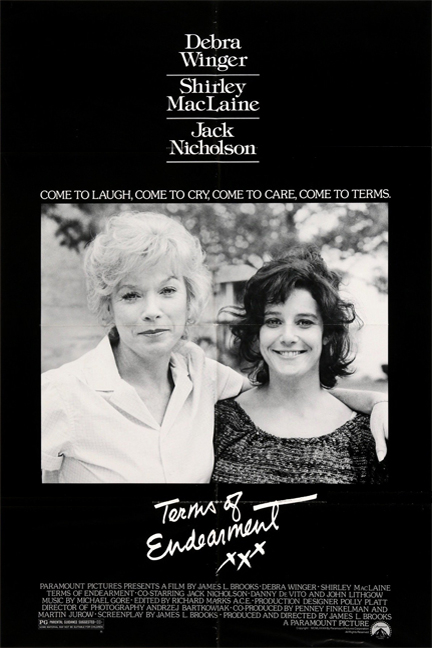

For those who missed it, the story (adapted from Larry McMurtry's 1975 novel) centers around blousy, neurotic Houston widow Aurora Greenway (Shirley MacLaine, who looks like she barely survived a freak explosion in a Laura Ashley warehouse), her erratic romance with lizard-like next door neighbour, retired astronaut Garrett Breedlove (Jack Nicholson) and her efforts to lord over the life of her perfect-opposite daughter Emma (gangly, earthy Debra Winger, never better.)

Reviews were generally positive, with critic Gene Siskel correctly predicting the film would get the Best Picture Oscar — a win that still rankles some folks after all these years.

The contrarian consensus is that The Right Stuff should have received the prize instead. I can't help but notice that most (but not all) of these writers are male. (Even Siskel eventually joined their number.)

Team Right Stuff appeals to that movie's considerable cinematic achievements, but these essays are also barely disguised paeans to the space program itself, which these writers consider self-evidently more worthy of attention than the chaotic lives of two women (and one decidedly non-heroic astronaut) here on Earth.

My hostility to NASA and all its works and pomps is longstanding and unshakable. The space program was a shameful waste of extorted tax dollars, all to fly to a rock in the sky that doesn't even have any cool animals.

Defenders retort that the space program has spun off a host of indispensable inventions, but such wonders, if truly crucial, would have been developed anyhow — perhaps even faster, and more cheaply, had the government left trillions in stolen cash in the hands of private enterprise.

In fact, a fictional "space program" has arguably inspired as many innovations as the real one, and as its sets — dressed with papier mâché boulders and (probably) Christmas lights behind cardboard — can attest, was far more cost-efficient.

Particularly bizarre are these critics' complaints that Emma's death from cancer was a deus ex radiation machina — a "lazy," "manipulative" way for writer and first-time director James L. Brooks to wrap up his episodic, multi-toned movie with a tearjerker conclusion.

Never mind that that very plot point was in McMurtry's novel.

Might I remind these critics that, while going to the moon is a rare event, dying of cancer is not. Who knows how many men and women do it every day. Sorry to harsh your geeky mellow and all, but Emma's job as a wife and mother looks just as hard as Gene Krantz's. Most of us live and die without accomplishing anything especially historic.

Don't we deserve movies too? Particularly movies as finely crafted as Terms of Endearment?

(Alchemy isn't science because its results can't be replicated, even with the same ingredients: A 1996 sequel, The Evening Star, isn't so much forgotten as unknown, and touted remakes have come to nothing.)

Not that some of Terms of Endearment's most ardent fans don't rankle a bit, too. And these are, tellingly, mostly women with cancer themselves, who give the impression that they never write about anything else.

This one calls it "my favorite movie of all time." (Since my tumors didn't strike my brain, I'll stick with Psycho, thanks. Hell, it isn't even my favorite cancer movie; give me Dark Victory any day.)

She interprets Emma's exasperated admonition — "It's OK to talk about the cancer!" — as a campaign slogan, as if, almost 40 years later, cancer isn't all anybody talks about. (I call it "Big Boob," a subsidiary of the Bourgeois Disease Complex.)

What these women often leave out are Emma's lines just before that one:

"I want you to tell them it ain't so tragic! People do get better."

Her cracking voice (and nervous, gawky gestures) are that of someone trying to convince herself of this, not so much her uncomprehending friend. Emma knows very well that some people don't.

I can't prove that Michael Gore's poignant, tinkly, oh-so-Eighties piano score for the movie was created in a lab, for the express purpose of forcing you to cry — but can anyone prove it wasn't? Regardless, Emma's death scene, and that darn music, pushed me over the edge.

Of course I cried — I cry during bits of Galaxy Quest.

My husband was in the other room and I called to him.

"I wahjj'd da sad moobee!" I blubbered at him through a Kleenex.

I got the hug I wanted, then some advice.

"Watch more funny movies from now on," he ordered. "It's science!"

But Terms of Endearment is funny and sad. Like life, and death — at least on our planet.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one. To meet many of your fellow club members in person, join Mark along with Conrad Black, Michele Bachmann and several others aboard our upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise down the Mediterranean.