On the rare occasions when movies — that most kinetic of artforms — dare to present men simply waiting around, still and silent, it's typically just a trick to ratchet up the tension before a gun fight, a la High Noon or Rio Bravo. Viewers are well aware that, soon enough, these motionless men will revert to all-out action mode, as characters with agency.

Women in film, on the other hand, usually wait around — often locked up or hiding — as a prelude to victimhood.

Think of the night-before-the-execution sequence in the 1958 Susan Hayward vehicle I Want to Live! as she (and we) wonder if the governor will phone in a stay. Those 12 or so minutes really do feel more like 12 or so tense and tedious hours, an impressive technical and artistic accomplishment.

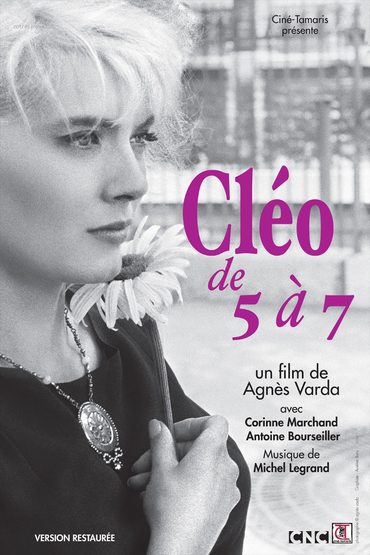

Likewise, Agnes Varda's Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) chronicles the titular heroine's two hour, pseudo-"real time" wait for the results of a cancer biopsy. (Turn on English subtitles):

Anyone who's spent time in the land of the sick quickly becomes all too familiar with waiting: To be seen by a doctor in the emergency room; for test results; for a drug to start working (or not); and, once convalescence begins, the humiliating wait between what have become the "highlights" of one's day: the next meal, the next bowel movement, the next episode of that old sitcom at three in the afternoon. Waiting is a nagging, suffocating side effect for which there is no treatment. Just to hammer the point home, it is no coincidence that Cléo... takes place on June 21, the longest (and therefore, slowest) day of the year.

What makes Cléo... revolutionary is that the main character — a flighty, vivacious twenty-something pop star of some small renown — does her waiting in impatient perpetual motion. She stuffs the first 45 minutes of the film with frivolous diversions like buying a silly hat, the better to distract herself from her possible fate.

She looks in every mirror (and there are lots of mirrors) as if to assure herself from one second to the next that she is still alive, and lovely: "Ugliness is a kind of death," Cléo tells herself, although we're not quite convinced she believes this, or much of anything at all. "As long as I'm beautiful, I'm more alive than others." There are also lots of clocks, arrayed like mute rebukes — Cléo can try to ignore her date with destiny, but Time will out.

At the 45-minute mark, however, Cléo's attitude changes abruptly. As her exasperated entourage tells her to stop worrying her pretty little neurotic head about what's sure to be nothing (and here the then-pervasive opinion that cancer should never be discussed is subtly introduced), Cléo rebels. She pulls off her wig, changes from a frou-frou white marabou get-up into a sleek black dress, and storms out to wander the streets of Paris, alone, for the last half of the film – and, we sense, for the first time in her life.

The prospect of dying has forced self-centred, juvenile Cléo to take the first steps into true maturity, and she's predictably shaky on her feet at first. But we watch her undergo a profound but believable personality change:

For instance, when we met her, she was chronically, childishly superstitious; later, when the mirror of her compact shatters, this isn't so much an omen of death as a symbol of liberation.

"I always think everyone's looking at me, but I only look at myself," she soon realizes — and something more. As Roger Ebert observed:

"When you fear your death is near, you become aware of other people in a new way. Yes, you think of the others, you think your life is going on its merry way, but think of me — I have to die. Cléo's awareness of that deepens a film that is otherwise about mostly trivial events."

In-depth conversations with others — a frank female friend who models nude for sculptors, a kindly, enigmatic stranger about to ship off to the French-Algerian War — broaden Cléo's perspective on her place in the world, as one human being among millions, all of whom have their own hopes, burdens and fears.

In fact, Cléo is so caught up chatting with her new soldier friend that she almost misses her doctor's appointment. When she finally receives her diagnosis, she displays a new-found serenity; she seems to have aged ten years, but in a good, long-overdue way.

Cléo from 5 to 7 is very much a Left Bank, nouvelle vague film, right down to a horribly dated and pretentious "silent movie" interlude. If the average Hollywood movie is an ice cream sundae, Varda's film is more like an olive, or sushi, or caviar. As an unapologetic fan of classic American "comfort food" cinema, I couldn't help but fantasize about how, say, Douglas Sirk would have handled the same material: Sending Sandra Dee traipsing through New York in a variety of fabulous candy-coloured outfits, accompanied by heart tugging music cues. The result would have been... cozier than Cléo. More sentimental, less austere. I would have "liked" it much more.

On the other hand, Cléo from 5 to 7's very un-Hollywood style is as bracing and "grown up" in its way as Cléo's own journey. And if you find yourself unmoved by her plight, you can at least savour a travelogue of a Paris that no longer exists.

But if you've ever been trapped in limbo, to learn what fate has in store for you, and not quite sure you're ready to deal with it, this is the very rare film that portrays that universal yet highly personal experience.

Cléo from 5 to 7 streams via iTunes, Netflix's DVD.com and the Criterion Channel.

~If you'd care to weigh in on Kathy's column, Mark Steyn Club members can chime in in the comment. If you aren't yet a member but want to get in on the fun, you can sign up or get a loved one a gift membership here. To meet your fellow Club members in person, consider joining our third annual Mark Steyn Cruise next October, featuring Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and fan favorite Michele Bachmann, among other distinguished special guests.