Peter Fonda died a few weeks ago, during this column's summer hiatus. He was an actor, son of the eternally iconic Henry, brother of the enduringly notorious Jane, father of the briefly famous Bridget - although, if you knew him only from his bonkers Twitter feed of recent years, you'd have assumed he was just another depraved anti-social social-media goon unable to get off the hamster wheel of Tourette's insta-commentary. This was marginally less tedious than the ever more cloying sense of his own goodness that his dad radiated in old age. As to the Fonda of earlier years, you may be interested in my old pals Bananarama's comments to me about encountering him on their first visit to America, back when we were young and he was merely in the early middle-age of his celebrity.

If a variable artist is lucky, death restores him in public consciousness to his peak - and Fonda certainly had his moments. I'm thinking not so much of Easy Rider, but of a film from three decades later. Ulee's Gold (1997) indirectly reunited Rider's star, co-writer and producer with Jack Nicholson, if only in that year's Oscar nominations, in which Fonda also found himself up against Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall and Matt Damon. Nicholson won, of course - for his obsessive-compulsive turn in As Good As It Gets. In his acceptance speech, Jack Nicholson, with a wicked smile, saluted his "my old biker pal Fonda". But it was no contest: Fonda's is the kind of performance that gets you a nomination; Nicholson's the kind that gets you the statuette. Starry but stricken wins every time.

Fonda had never been that kind of player. Even with Nicholson in Easy Rider half-a-century earlier, he was content just to be. While Jack and Dennis Hopper roared off down the highway, Fonda seemed to be left there in the dust: long, lean, laconic, and looking — even in the middle of a supposed "counterculture" movie — as if he were modelling for a Madam Tussaud's effigy of his father. Père et fils shared a distinctive saggy-shouldered celebrity, both men perambulating as if their centers of gravity were located in their knee ligaments: I would have liked to see either do the "Broadway Rhythm" number in Singin' in the Rain.

Thirty years on, Ulee's Gold was Peter's premature B-movie of Henry's On Golden Pond. Actually, make that a bee movie. Peter plays Ulee Jackson, a beekeeper, and the camera lingers as lovingly over his beloved bees in the northern Florida swamps as it did over the loons of New Hampshire in Golden Pond. Victor Nuñez isn't so much an American director as a Floridian one: he's made four films there and in each case the story, such as it is, seems little more than a pretext to examine some aspect of life in his backyard. In this case, it's beekeeping and honey — not that cheapjack Chinese stuff you get in too many supermarkets these days, but the high-quality "tupelo honey" that Ulee and his bees painstakingly draw from the swamps (Van Morrison sings his song of the same name over the credits). That's the gold of Ulee's Gold, and you get the feeling Nuñez would have been happy to leave it there, quietly lapping up the lazy lushness of the landscape and the hum of the bees.

But this is a drama not a documentary, so he's had to come up with a plot and thus, as things transpire, out there in the bayou in an old cooler jammed under the seat of a rusting pick-up is quite a different kind of gold. Ulee learned beekeeping from his father, who learned it from his. But times change: Ulee's son is in the state penitentiary, his daughter-in-law's a junkie, his sullen teen granddaughter seems headed the same way, and, at the height of the tupelo season, his boy's two thug accomplices show up from Orlando in search of the loot.

In On Golden Pond the principals were dysfunctional in their intra-family relationships; in Ulee's Gold they can't function in any sense and, like too many families in the backwaters of America, they're downwardly mobile, mired in a psycho-swamp of their own. If the problem with the plot is that we've seen it a zillion times before, it's rarely the story and almost always the storytelling. So there's something engaging merely in slowing down the familiar outlines of a cookie-cutter crime thriller to Nuñez's ruminative (at times comatose) pace and putting them in a bright particular setting. As for the eponymous character, Fonda said he "found a lot of Ulee in my father. He kept a couple of hives and I can see him hop-footing it across the lawn, thinking he had a bee up his pant leg. As I began to develop Ulee, I used a lot of the way my father was to us as kids, the way he was to us as a family and the way he was to himself." It's easy to believe in Fonda as a beekeeper, less easy to believe that he has any biological connection with this family of misfits from the darker corners of the Sunshine State. "There's all kinds of runnin', Ulee," the drug-zonked daughter-in-law tells him. "Your body might have stuck around ...but your heart took off a long time ago." There are all kinds of families like that, aren't there? Inhabiting the same space but long separated. But, with Ulee, it's his body that seems so at odds with the rest of his household. While son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter all look serviceably scuzzy, Fonda, an actor of limited expressiveness, nevertheless can't help but project a sort of earnest nobility. Maybe Ulee should have got a blood test.

Ulee stands for Ulysses, though you wouldn't know it. Instead, Ulee stands for anything: the worst humiliation provokes only the same weary, weathered stare. Peter's always had the flat-footed gait of his dad, but here he's eased into the wire-rimmed specs, too. It's the classic Henry Fonda role: the soft-spoken loner whose unperturbability is mistaken for weakness. As his other granddaughter, seven-year-old Penny, puts it, in her explanation of beekeeping: "You've got to keep calm and don't panic when they sting 'cause they don't mean nothin' by it." Ulee's family sting him continuously, but he keeps calm and he doesn't panic. This metaphor is all Nuñez does to connect up the two halves of his film — the honey and the money — but, crude and bald as it is, it somehow suffices.

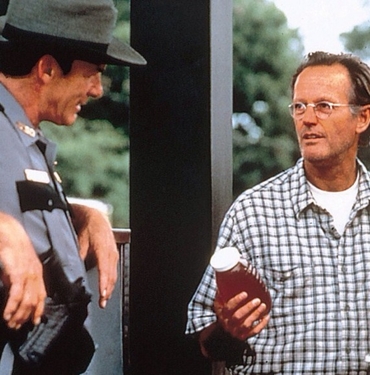

Like other sensory cinema, from Meet Me in St Louis to Jean de Florette, Ulee's Gold functions as a luxuriant soak. Once you settle into the story, Fonda and the beekeeping and Nuñez's direction gradually achieve a kind of harmonic convergence. You forgive the director-writer the neon signposting of his dialogue: "Look, you can't stay cut off forever," the sheriff tells Ulee two minutes into the picture, for those who like their story themes spelled out in capitals. You forgive him, too, the patness of his plot mechanics — the conveniently situated nurse next door, pleasantly played by America's favourite sitcom mom of the era, Patricia Richardson from "Home Improvement". None of these matter because of the casting: after years of floundering, Fonda finally found a milieu and a director even stiller and more measured than he was. Three decades after Easy Rider, he was at last back in the saddle.

~As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before in its sixteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time; it's also an audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle (the latest aired last week). We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have many other benefits, and an upcoming cruise. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership that makes a great birthday present. More details here.