Three quarters of a century ago - September 1944 - this week's song was in the midst of a nine-week run at Number One on the Billboard pop chart. It's stuck around through all the decades since - which is unusual because it's not a timeless love ballad, but rather a cautionary tale for slacker schoolkids set among the grubbier habitués of the barnyard. It was introduced earlier that year in the film Going My Way, in which Bing Crosby played an unconventional Catholic priest and Barry Fitzgerald tagged along heavy on the blarney. The movie was a smash, cementing Bing as the Number One box-office star and cleaning up at the Oscars with a haul that included Best Picture and, for its leading man, Best Actor.

The plot hinged on the crippling mortgage with which St Dominic's Church was burdened. Bing's Father O'Malley had written a ditty that exemplified his personal if somewhat doctrinally dubious philosophy, "Going My Way", and the priest and his operatic ex-girlfriend, Risë Stevens, cook up a plan to rent the Metropolitan Opera for the day and sing the number with a full choir and orchestra to impress a bigshot music publisher into snaffling up the song and alleviating St Dominic's financial woes. Yeah, I know it sounds ridiculous when you type it out like that in cold print, but, if it's any consolation, it sounds ridiculous up on the big screen, too, even in a musical, even in the mid-Forties.

The fatal flaw in the scheme, which might have been foreseen, is that, having heard the song, the music biz exec decides to pass on the song because he thinks it's a big blah that won't sell. In a desperate attempt to save the day, Father O'Malley, his ex-, the choir and the orchestra launch into a second number - and this time the publisher likes it.

Life imitates art. "Going My Way" was, indeed, a big blah - making the charts for just one week, at Number Fifteen, which, for a guy who was king of the hit parade through the Forties and warbling the title song of the year's biggest picture, was something of a humiliation. But that second tune from the ill-starred Met-for-a-day gig was the real deal - and, after "San Fernando Valley" and "I'll Be Seeing You", gave Crosby his third Number One of 1944:

That's Bing with a workmanlike arrangement by his trusty musical director John Scott Trotter and backing vocals by the Williams Brothers - Bob, Don, Dick and the baby of the quartet, Andy. It was the first hit record on which the siblings sang, and it led to tour deals, nightclub acts, and for young Andy Williams a stellar two-thirds of a century.

The authors of the song were a team called Burke & Van Heusen. Johnny Burke wrote the words, Jimmy Van Heusen the music, and Bing was the de facto third member of the duo: They were his in-house songwriters, and he was their out-of-the-house drinking buddy. Van Heusen played a big part in the celebrification of Palm Springs: He was one of the earliest Hollywood guys to take a pad in the California desert, liked the life, and tempted first Crosby and then Sinatra to join him. And the two preeminent interpreters of America's standard repertoire liked to have Jimmy close at hand for whatever was needed: thirty-two bars of music, eighteen holes of golf, a round apiece at eighteen bars or thirty-two watering holes... In my Sammy Cahn centenary podcast, I reprised a line Sammy used on me many years ago:

Every man in the world wants to be Frank Sinatra. Except Frank Sinatra. He wants to be Jimmy Van Heusen.

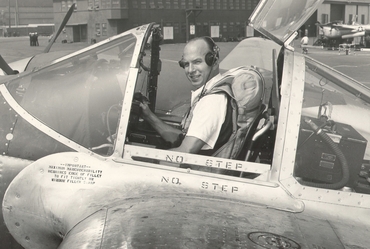

Sammy says on the show that Jimmy had "a lust for life" - and not just for the things successful showbiz types usually lust over. Thus, Van Heusen isn't merely the guy who composed "Come Fly With Me", he flew fighter jets as a test pilot for Lockheed Martin; if you were so minded, you could come fly with him. On the podcast, you'll hear Sammy tell me:

When people said to me 'Who's the most fascinating man you ever met?', that's easy: Jimmy Van Heusen.

'Jimmy Van Heusen? What about Sinatra?'

Sinatra thinks he's Van Heusen but he can't pass the physical.

I laughed, and Sammy said, "And that's not a joke."

Frank and Jimmy, hard-living, hard-working, hard-playing and hard-drinking, stuck together till the end - and beyond: Van Heusen is one of only two non-Sinatras to be buried in the Sinatra family plot (the other being Frank's pally, restaurateur and sometime bodyguard Jilly Rizzo). Just as Ol' Blue Eyes snaffled Van Heusen away from Bing and Johnny Burke and paired him with Sammy Cahn, so a generation earlier Bing and Burke had snapped up Van Heusen to supplant an earlier member of the team.

Johnny Burke was dubbed by his fellow lyricists "the Poet" and by Cahn as "the Irish Poet", and like many Irish poets he enjoyed a tipple. It ended his career, and eventually his life, a couple of decades ahead of his principal collaborators and equally prodigious drinkers, Crosby and Van Heusen. But in the twenty or so years he was at his peak, Burke produced a catalogue of songs that puts him in the very top tier of lyric-writers. He was born in 1908 in Antioch, California, and he hit his stride around his thirtieth birthday, writing classic ballads, rhythm numbers, comedy novelties ...and what Sammy Cahn acknowledged to me over lunch one day as "the all-time greatest animal song":

But if you don't care a feather or a fig

You may grow up to be a pig.

Burke dealt in a lot of conventional Tin Pan Alley imagery - the stars, the moon, the heavens - but the celestial stuff was lightly worn:

Would you like to swing on a star?

Carry moonbeams home in a jar?

Come again? Carry moonbeams home in a jar? That's one of those potentially perilous images that few writers could pull off. Years ago, I wrote a little comedy sketch featuring a fey hippie chick called Carrie Moonbeams (and revived her, briefly, here), and the actress playing her said, "Wow, what a great name! Where'd you come up with that?" "Oh, you'll figure it out," I said. It's one of those goofily memorable phrases (like "reindeer games" in "Rudolph") that only a popular song can embed in the language. Burke's words swung among the stars but rarely lost their footing. Take "Moonlight Becomes You":

You're all dressed up to go dreaming

Don't tell me I'm wrong

And what a night to go dreaming

Mind if I tag along?

After trembling on the brink of over-ripe grandiosity with "all dressed up to go dreaming", the casual conversational throwaway - "Mind if I tag along?" - is just lovely set against the lush flow of the melody.

Burke grew up in Chicago, played piano in the orchestra at college, and then joined the Irving Berlin Company as a song plugger. He was teamed with an up-and-coming composer called Harold Spina and in the early Thirties they wrote, among other things, some wonderful novelty songs for Fats Waller - "You're Not The Only Oyster In The Stew" and "My Very Good Friend, The Milkman". Then Hollywood called, and Burke hooked up with a composer called James V Monaco - "Ragtime Jimmie", whose hits, as the sobriquet suggests, went way back, to "Row Row Row (Way up the river)" and "You Made Me Love You (I didn't wanna do it)" before the Great War. Monaco & Burke wrote songs for Crosby pictures: "Pocketful Of Dreams", "An Apple For The Teacher", and a number whose title is the very definition of Bing's deceptively careless ease, "That Sly Old Gentleman From Featherbed Lane". There is an actual Featherbed Lane I pass from time to time, and its street sign never fails to evoke Burke's title phrase and Crosby's warm baritone.

Burke & Monaco's songs served Paramount's plots, just about, and did okay-ish on the hit parade, but, considering they were being introduced by the biggest pop star on the planet, Burke felt they should have been doing better. In 1940 Bing teamed with Bob Hope for a film called Road to Singapore: Everybody understood they had the makings of what we would now call a blockbuster "franchise" on their hands - and, indeed, the Road films would become the most successful film series in history until James Bond came along.

But if only the songs had had a little more oomph...

One day Johnny Burke went over to Warner Bros and strolled into the office of an up-and-coming composer. "Got any tunes?" he asked.

Jimmy Van Heusen was surprised by the question, but anxious to please. "Sure," he said.

And so Burke & Monaco were succeeded by Burke & Van Heusen, and both men were embarked on what would prove the most important partnership of their careers. Jimmy Van Heusen had started out in life as Chester Babcock and as a teenager got a job at his hometown radio station - WSYR in Syracuse, New York, which now, alas, is reduced to carrying my guest-hosting stints on America's Number One show and whose morning man Dave Allen was kind enough to introduce me on stage when I was in town earlier this year. Almost nine decades before I showed up, young Chester Babcock was told by the station manager that he needed a better name on air, and was ordered to find one pronto. Chester looked out the window to see a shirt manufacturer's truck parked outside, with a classy name emblazoned thereon. So "James Van Heusen" became a Hollywood composer, and "Chester Babcock" was affectionately retained as the name of Bob Hope's character in the later Road pictures. It didn't really matter what either Van Heusen or Burke was called: Once they formed their partnership, they were a two-headed creature called Burke-&-Van-Heusen that wrote as one and drank enough for ten.

"There was a little feeling about Burke & Van Heusen," said David Butler, director of Road to Morocco, "because Jimmie Monaco and Burke were partners, and Burke pulled away from Monaco and got Van Heusen. Jimmie Monaco felt very bad about it. But he came up with 'Six Lessons from Madame La Zonga' right after that, and it was a big hit. He was a great guy."

Crosby thought so too. So, in honor of a great guy, he named one of his many racehorses Madame La Zonga. But song-wise he understood that with Van Heusen he was definitely trading up.

Jimmy liked booze and broads, and, if the latter interfered with the former, he moved on. Yet a composer who apparently never needed any enduring love of his own wrote some of the most enduring love songs for everybody else, with beautifully relaxed, moonily meandering tunes of long sinewy phrases - "Like Someone in Love", "Here's That Rainy Day" - to which Burke put lyrics that are modest and rueful and touching, and whose understatement makes the melody perfectly bewitching.

"Swinging on a Star" is not one of those songs.

For Going My Way, the director Leo McCarey told Burke and Van Heusen that he wanted sermon-like songs - songs that Father Bing could warble to teach Biblical lessons in music. And McCarey sang them an approximation of the sort of thing he had in mind, called "Rhythm in the Catechism".

The two writers were not enthused by that. For years, Burke had taken the view that he was Bing's house lyricist, and therefore the best way to write words that Crosby would sing was to pay attention to the words that Crosby spoke. So he would "either take my phrases directly from him or pattern some after his way of putting phrases together". One day Burke and Van Heusen were round at Bing's place, and found their host bawling out his oldest boy Gary. The nine-year-old pushed back, until his dad brought the argument to a close with "Fine. You wanna be a mule, be a mule."

And the songwriters had their song:

Would you like to swing on a star?

Carry moonbeams home in a jar?

And be better off than you are?

Or would you rather be a mule?A mule is an animal with long funny ears

He kicks up at anything he hears

His back is brawny but his brain is weak

He's just plain stupid with a stubborn streak

And by the way if you hate to go to school

You may grow up to be a mule...

Burke & Van Heusen called the song "The Mule", and in fact it's referred to as such in Going My Way. But that's not really a hit title (at least not without "Train" stuck at the end), and a far better one was staring them in the face. Indeed, when Sinatra got around to recording the number twenty years later, it certainly wasn't because he was looking for a song about a mule: It's pretty clear, when you listen to him riding Nelson Riddle's chart, that he likes "Swingin' on a Star" because he's a star who digs swingin'.

Aside from anything else, the form of the song - the eight-bar "carry moonbeams" chorus followed by twelve-bar verses - demands a whole menagerie, far beyond a solitary mule. So enter a pig and a fish and, by way of the tag, monkeys. And suddenly the authors of "But Beautiful" and "It Could Happen to You" and "Polka Dots and Moonbeams" had a monster hit with a kiddie song. A couple of years later, Little Lulu, a popular children's character from The Saturday Evening Post, made an animated short of the song:

And that's where it might have remained - as a children's novelty. Certainly, Bing sang it in those early years, but he tended to view it as a piece of special material. Here's his second big-screen performance of the song, from 1945, in Duffy's Tavern, a film version of the hit radio sitcom. "Duffy's Tavern" was co-created by Abe Burrows, whose son James went on to co-create a 1980s TV variant on the theme, "Cheers". On radio "Duffy's Tavern" was wont to feature celebrities playing themselves, and for the silver screen they had a barrelful. Here's Bing with Sonny Tufts, Cass Daley, Diana Lynn, Billy De Wolfe, Betty Hutton, Dorothy Lamour and more, using "Swinging on a Star" as a kind of parodic masterclass in acting:

If you object to that rewrite of Johnny Burke's lyric, well, it's by a guy called Johnny Burke.

Burke would provide twenty-five film scores for Crosby and give him six number ones. "Comes Love," as he wrote, "nothing can be done." But comes booze, even less could be done, and when Bing and Jimmy Van Heusen reckon you're drinking too much, that's the gold medal in the Bibulous Olympics. As the Fifties proceeded, Burke faded to a blur - he grew "Misty", as his last hit put it - even as his old catalogue blazed ever brighter. Here's Rosie kicking loose with "The Mule", even as she's still pretending it's a kiddie class:

"Swingin' on a Star" swings, but it doesn't have to. It was still young when rock'n'roll and doowop and rhythm'n'blues blew away old-school Tin Pan Alley, but, amidst all the raucous guys, there were a lot of vocal groups around in need of material. Here's Dick Clark, delivering a long introduction alongside a noticeably unenthused sock-hopper, with Dion and the Belmonts, who'd had a big hit wondering "Why must I be/A Teenager in Love?" One way to stop all that teenybopper solipsism is to sing a grown-up song, so they had an even bigger hit with Rodgers & Hart's "Where or When" and then went prowling the rest of the standard repertoire:

Dion, as he would prove with "The Wanderer" and "Runaround Sue", could rock it up with the best, but that's a comparatively genteel "Swingin' on a Star". The definitive rockerization came along a few years later and hit Number Seven in the UK Top Ten in 1964:

That's Big Dee Irwin doing Johnny Burke's lyric, with Little Eva in the fill ("I don't wanna grow up to be a mule") transforming a solo into a passable duet. And so for a generation of rockers the arrangement became the song, and for a while everyone did "Swingin'" that way - for example, the Tremeloes record faithfully duplicates all Little Eva's asides ("One moonbeam, two moonbeams...").

There are worse things to inflict on a song, though. My late friend Dick Vosburgh, with whom I used to do a terrible BBC Light Entertainment show (the fault was mostly mine, not his), had an idea for a series called "Singers Are Stupid", which Radio 2 eventually let him host under a less brusque title. As Exhibit A for the proposition that "singers are stupid", Dick liked to cite Burl Ives' record of "Swingin' on a Star". The actual song goes like this:

A fish won't do anything, but swim in a brook

He can't write his name or read a book

To fool the people is his only thought

And though he's slippery he still gets caught

But then if that sort of life is what you wish

You may grow up to be a fish...

Burl sings it:

But then if that sort of life is what you want

You may grow up to be a fish...

Dick could never understand how a guy could sing "school" and "mule", "fig" and "pig", and then "want" and "fish" without either the vocalist or anybody else in the room figuring that something didn't feel right. On the other hand, having pointed out a flaw in a record, I'll note what I always feel is a minor blemish in the song - from Burke & Van Heusen's tag, to wrap up the number and its moral instruction:

And all the monkeys aren't in the zoo

Every day you meet quite a few

So you see it's all up to you

You can be better than you are

You could be Swingin' on a Star.

The ear hears "and all the monkeys aren't in the zoo" as "all the monkeys are in the zoo". Burke could as easily have written "not all the monkeys are in the zoo" or "not ev'ry monkey lives in the zoo" or any other more singable variation. But he didn't - because "the Poet" was an assignment writer, up against a hard deadline, and there wasn't always time for buffing and polishing. And, even if you're minded to change it, by then everyone loves the song as is.

Likewise, having noted Burl Ives' crazy record, here's a Psycho one, by Anthony Perkins. Perkins was a star who swung a little too promiscuously (Tab Hunter, Rudolf Nureyev, Stephen Sondheim, Victoria Principal) and died too young of Aids. (His widow Berry died aboard American Airlines Flight 11 when Mohammed Atta flew it into the World Trade Center.) But he loved songs, and, on the only occasion I met him, we spent a merry ten-minutes swapping obscure lyrics. Tony Perkins would never have rhymed "want" with "fish":

In his book The House That George Built, the late Wilfrid Sheed writes that Kathryn Crosby mentions a letter Frank Sinatra wrote to Bing shortly before the latter's death in 1977, expressing concern over Jimmy Van Heusen's drinking. "I know," she said with a smile, "I know..." As Sheed puts it, "Any one of them could have written the note about any of the others."

But by then the fourth hard-drinking musketeer, Johnny Burke, was a long time in his grave, having expired at the age of 55 in February 1964, even as "Swingin' on a Star" was back in the charts.

As for Kathryn Crosby, her step-sons handled booze and (reflected) celebrity even less well. After inspiring "Swingin' on a Star", young Gary Crosby joined Bing for a duet on "Sam's Song" and "Play a Simple Melody" that became the first double-A-side gold record in history. Thirty years later, his career on the skids, he was reduced to publishing Going My Own Way, a memoir excoriating his father as an alcoholic and abuser. He died of lung cancer in 1995. By then two of his brothers were also gone: Lindsay shot himself in 1989, and Dennis did likewise two years later. The Crosby kids' lives make a bleak contrast with the Sinatras'.

But all that is too much weight to place on a swingin' barnyard caper. To be sure, the choice presented in "Swingin' on a Star" is a false one, between carrying moonbeams home in a jar, and being a pig. Most of us fall somewhere in between. But the title of the song exemplifies the Johnny Burke style, for all his over-indulged appetites: To modify Oscar Wilde, a lot of drunks are lying in the gutter, but few of them are swingin' on a star.

~Don't forget, some of Mark's most popular Song of the Week essays are collected in his book A Song For The Season. You can order your personally autographed copy exclusively from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing.

The Mark Steyn Club is now in its third year. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that thanks to the Steyn Club this site now offers more free content than ever before in our sixteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits - and the Third Annual Mark Steyn Cruise, on which we always do a live-performance edition of our Song of the Week. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.