The term "midlife crisis" was coined by psychoanalyst Elliott Jaques in 1965. The English language somehow made do without that phrase for the previous six hundred years, yet today, could we get along without it?

In 1900, the average American male life expectancy was 47. In 1965, it was 67. An additional two decades of existence: More time to ruminate about your time running out.

In this as in so many instances, art preceded (social) science: The then-nameless male midlife crisis had been explored before, through farce (1955's The Seven Year Itch), then high-brow literature (John Cheever's classic 1964 story "The Swimmer.")

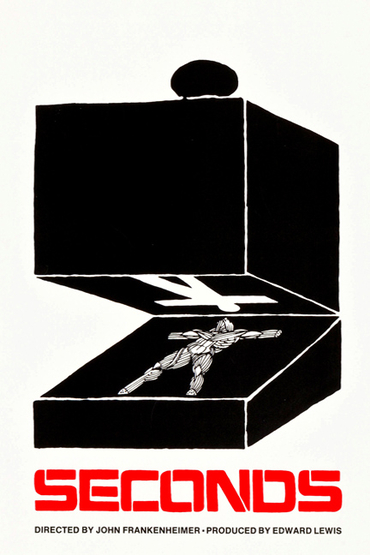

For whatever it's worth, the first movie made after Jaques' "discovery" was John Frankenheimer's Seconds (1966), starring Rock Hudson. (Eventually.)

First we meet Arthur Hamilton as played by John Randolph, an aging banker with a stereotypical mid-20th century American suburban existence: big, well-appointed house; dutiful wife; married-off daughter; a white-collar commuter job for life, until he retires with a gold watch and a pension.

Suburbia: A life and location that's been targeted by smug American satirists since the paint dried on the first tract house. Of course, it's also the kind of safe, clean, comfortable lifestyle that millions of un-smug non-Americans would give almost anything to enjoy.

Arthur Hamilton isn't enjoying it.

In most movie depictions of male middle class midlife crises, the protagonist steeps himself in daydreams: Playing Rachmaninov to the gorgeous upstairs neighbor; "swimming home" from pool to backyard pool; whatever the hell was going on in 1999's American Beauty (which, from the sounds of it, I was right to avoid.)

Seconds is the most fantastical of these tales (it's based on a science fiction novel) yet what happens to Hamilton is, within the four corners of the film's frames, presented as all too real.

Through a series of unsettling encounters, including phone calls from a "dead" friend, Hamilton is tempted by – then forced to accept – a chance to start all over again.

A shadowy entity called "The Company" will fake Hamilton's death. Then, through plastic surgery, he will be transformed into one Tony Wilson, a younger, handsome and accomplished painter living in Malibu, now played by Rock Hudson.

(Think of The Stepford Wives, except this time the husband makes himself over instead of his unknowing spouse.)

What man wouldn't want to wake up looking like Rock Hudson, living the life of a famous artist, frolicking on a California beach with a vivacious girlfriend?

Hamilton, that's who.

But by the time he realizes his exciting new life is as empty as he believed his old one to be — that wherever you go, there you are — it's too late to turn back....

I first watched Seconds on Canadian public television in the 1990s, and only because it was directed by John Frankenheimer. His The Manchurian Candidate (1962) was and is a personal favorite, and Seconds displayed a similar sensibility: jarring forced perspectives and askew camera angles; a plot revolving around a sinister, secret cabal, and splintered identity.

The film also boasts a perfect score by Jerry Goldsmith, brilliant-as-usual opening credits by Saul Bass, and mind-blowing cinematography from the all-time master of black & white, James Wong Howe. (Seconds shows up on many cinematographers' "top ten" lists).

All that added up to a film I thought was "cool" because it was "trippy" and grimly satirical, like then-trendy Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet. In those days, I also shared every aging punk's affinity for songs and movies bashing suburbia (a place I'd never lived in.)

However, my own middle age seemed a century away and anyhow, this was about a man, so I didn't register many pangs of sympathy towards Rock Hudson's Virgil-less journey through hell. That came later.

It will surprise no one who's watched even brief clips of Seconds that it bombed when it was released, to the point of being booed at Cannes:

"[T]he people who wanted to see Rock Hudson did not want to see this kind of film, while the people who wanted to see this kind of film did not want to see Rock Hudson in it."

Seconds experienced a revival of interest, and a reputation rehab, when it was released on DVD in 2002, which led to a feature-packed Criterion Blu-Ray edition in 2013.

And indeed, there is a lot to ponder:

Much has been written about the multiple subtexts of Seconds — the Hollywood "blacklist," as well as Hudson's then-secret (more or less) gay identity; the crazy "Brian Wilson connection"; the extraordinary lengths to which Wong Howe and Frankenheimer went to realize their vision: For one thing, to thin out a section of Grand Central Station to capture their opening shots, they hired a woman in a bikini to create a crowd-forming spectacle at the other side of the terminal.

And all these factors do indeed add invisible yet palpable depth to a film that is in and of itself a stunning feat of storytelling, acting and technical prowess.

Liberal fans of Seconds praise it as — you guessed it — a chilling condemnation of shallow materialistic American consumerism and conformity. Yet few of them mention that when Hamilton gets his twice in a lifetime opportunity to savor the idealized progressive lifestyle instead, he's miserable then too. Actually more so.

In fact, coming out as it did in that pivotal year between the early Sixties New Frontier/Mad Men era, and the late Sixties of Woodstock and Manson, Seconds could just as easily be read as a critique of the then-nascent youth "drop out" counterculture.

What Hamilton's old life and his new one share — besides their "top down," poorly-grafted-on nature, neither of which he consciously chose for himself — is success. Especially in his second life, success comes ready-made, as much a bought-and-paid-for accessory as his new hair and home.

Hamilton's real problem may be that he doesn't feel he deserves his success because he didn't have to struggle much to achieve it, either time.

I still find the last scene in Seconds, even after repeated viewings, utterly gut-wrenching, a richly enigmatic shot that makes we wonder if Hamilton is remembering himself as the parent, or the child, he used to be.

Or maybe he was recalling another fellow altogether: A father and a family he'd seen joyfully cavorting on some beach one apparently forgotten afternoon — the memory of which will be the last thought he ever has.

Even in his final moments, Hamilton is preoccupied with envy of a sort, and those elusive, shapeshifting desires for which there are no words.

I'm not the same person I was when I first watched Seconds, and still more ironically, I've become one of those admirers who feverishly pushes this movie upon any uninitiated individual I manage to corner.

You can thank me, or curse me out, later.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of her latest write-up in the comments. If you'd like to get in on the action, commenting is but one of many perks that comes along with Club membership. If you enjoy the camaraderie amongst fellow Steyn fans, you'll love it more at sea. The 2020 Mark Steyn Cruise – Mark's third annual voyage – is still open for bookings for those wishing to sail with Steyn and his special guests down the Mediterranean.