Fifty years ago this weekend - on July 21st 1969 - man walked on the moon. More particularly, they were American men, in middle age and of the mid-twentieth century. And so they took a cassette machine with what we would now call a "mix tape" - Peggy Lee's version of "Spinning Wheel", Glen Campbell's "Galveston", Streisand's "People", and Buzz Aldrin's particular favorite: "Fly Me to the Moon", as recorded by Frank Sinatra with the Count Basie band. And, as Nasa reported, the last became the first (human) music to be played on the moon.

Buzz Aldrin was perhaps more spaced out by space than any other of that golden generation who got to play among the stars: On his return to earth he fell into depression and alcoholism and family troubles. His own mother - maiden name of Moon, as it happens - had taken her own life a year before her son's historic mission because she thought it would end in disaster, and, even though it didn't, Aldrin came to find its success almost as big a pain. He hated the way, every time he entered a restaurant or a nightclub, the band would strike up "Fly Me to the Moon", and in later years would protest that he was sick of the song and had never liked it and would occasionally deny that he'd ever played it up there.

But contemporary accounts suggest he did, in a characteristically American and very human commemoration of one of the most significant events in the life of the planet. In 1961 President Kennedy had challenged America to put a man on the moon within the decade. Putting an American song on the moon took a little longer - a decade and a half - and the man who wrote it would be as unlikely a contender for such a breakthrough as one can imagine. The story of "Fly Me to the Moon" begins with a line from Johnny Mercer:

Writing music takes more talent, but writing lyrics takes more courage.

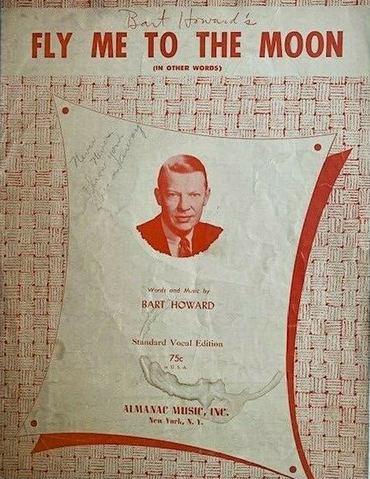

What he meant was that a tune can be beguiling and melancholy and intoxicating and a lot of other vagaries, but there comes a moment when you have to sit down and get specific, and put the other half of the equation on top of those notes. A songwriter spends his life chasing the umpteenth variation of "I love you", and that takes courage because there's usually a good reason why no one's used your variation before: the thought's too precious, or clunky, or contrived. So in 1953 a man called Bart Howard sat down to write a love song. He had been writing music and lyrics for twenty years, without anything to show for it. But, for once, as he put it, "it just fell out of me". In twenty minutes, he had a number that was full of all the usual stuff – moon, stars – and yet not so much topical as prescient. It's the only hit he ever wrote, and he didn't need another. He called it "In Other Words".

Never heard of it? That's because Howard didn't know what he was sitting on. What hits you aren't the "other words", but the first five:

Fly me to the moon...

You might know it by any one of a thousand versions - by Peggy Lee, or Tony Bennett, Astrud Gilberto or Marvin Gaye, Agnetha (the blonde from Abba) or Amy Winehouse... You might know it from the opening of Oliver Stone's valentine to the "decade of greed", Wall Street: the city at dawn, the trains and ferries and buses feeding the workers into the city, thousands of strap-hanging stick figures, pouring up from the subway tunnels and on to the teeming sidewalks of Lower Manhattan. And above the skyscrapers Basie plays and Sinatra sings:

Fly Me To The Moon

Let me play among the stars

Let me see what spring is like

On Jupiter and Mars...

The song makes the scene. Without it, it's nothing: for what is drearier and more earthbound, more literally everyday than commuting? But not when it's accompanied by Basie and Sinatra and a Quincy Jones arrangement that starts low-key with bass and tweeting flutes and surges into blaring brass rocketing into the skies. It's what Nelson Riddle meant when he called his preferred 4/4 swing for Sinatra the "tempo of the heartbeat". It's what Bono had in mind when he said "Frank walks like America. Cocksure." And, of course, it's what Gordon Gekko renders more crudely in his "greed is good" speech: all the possibilities of the day ahead, all the dreams and ambitions of the anonymous figures down in the tunnels articulated in music and, like the buildings, reaching for the stars.

And none of this is anything Bart Howard had in mind for his song. "I didn't know what I'd written," he told me a few years ago. Upon his death in 2004, NPR's Michelle Norris announced that they'd be paying tribute to "the man who wanted to see what spring is like on Jupiter and Mars". But that's exactly what Howard didn't mean. He couldn't have been less interested in what spring is like on Jupiter and Mars. His little-heard verse sets up the premise:

Poets often use many words

To say a simple thing

It takes thought and time and rhyme

To make a poem sing

With music and words

I've been playing

For you I have written a song

To be sure that you know what I'm saying

I'll translate as I go along...Fly Me To The Moon

And let me play among the stars

Let me see what spring is like

On Jupiter and Mars

In Other Words

Hold my hand

In other words

Darling, kiss me...

In other words, Howard wasn't reaching for the stars, but trying to bring the airy, high-flown sentiments of romance back down to earth. He called the song "In Other Words" because that's what it was about – what we're really saying underneath all the moonlight-becomes-you starry-eyed hooey. He wrote it for Mabel Mercer, whose accompanist he was in the post-war years, at Tony's on 52nd Street. In its first decade, "In Other Words" was picked up by all Manhattan's cabaret darlings – Kaye Ballard, Portia Nelson, Felicia Sanders:

They sang it as it was written, in rather stately waltz time. Among those early versions, I always find Mabel Wayne's one of the more expressive interpretations, especially once the second chorus kicks in with that 4/4 pulse:

But, whether in three-quarter time or slow ballad tempo, there's nothing Bono would find "cocksure" in there. Instead of that supreme Sinatra confidence, it sounds wistful and tentative.

Pretty much all Howard's compositions did in those days. His other great flying line comes in another cabaret song called "Walk-Up", a recollection of the urgency of love in a cheap flat up the stairs on the fourth floor:

There was a time when that walk-up of ours

Was just a hop, skip and jump to the stars..

Ev'ry night we flew each flight of stairs.

It's an intimate, rueful lyric, but a little too special, too particular for mass appeal:

Bart Howard's cabaret songs from the Fifties seem so specific to that world, and a little exclusive of everybody else's. He wasn't wealthy and nor were his friends, but even a fourth-floor walk-up had a kind of glamour to a boy from Burlington, Iowa. "He was the epitome of a certain kind of New York elegance that people that came to New York aspired to," said Jim Gavin, author of Intimate Nights: The Golden Age Of New York Cabaret. Howard was homosexual, and that was easier in the city, too.

He started out at sixteen, playing piano in a dance band through the Depression. Like Bob Hope, he worked with the Siamese twins Violet and Daisy Hilton, accompanying them at the piano through their lively three-legged tap routines. Howard moved on to play for the drag act Ray Bourbon, and eventually to New York, the Rainbow Room, and the life he'd wanted all along. It's a small, in-the-know world, and "In Other Words" is tailored for it, at least in its suggestion that big, bellowed professions of love are not what really matters.

In 1953, he finished up "In Other Words", and took it to his publisher, who'd been urging him to cut the clever stuff and write something more "commercial". The guy loved everything about the new song except that first line of the chorus. "Fly me to the moon"? Nobody said "fly me"; it didn't sound right. How about switching it to "Take me to the moon"? Howard resisted, which was just as well. There were over a hundred recordings in the next few years, and "In Other Words" never did take flight. As Peggy Lee grasped, you really need the verse - all that stuff about "translating as I go along" - for the title phrase even to be comprehensible:

Peggy Lee recorded "In Other Words" at the very beginning of a new decade: February 1960. And shortly afterwards, being a skilled and shrewd songwriter in her own right, she suggested re-naming it "Fly Me To The Moon" - because that's the obvious hit title "In Other Words" was never going to be. The space race was underway, and a chi-chi ballad for the cognoscenti suddenly seemed in tune with the times. There were new rhythms in the air, too. Peg's musical director at the time was Joe Harnell, and in 1962 he was injured in a bad car crash, and unable to conduct or, inter alia, play the piano on the Dinah Shore TV show. So while he was laid up the record company asked him to knock off a bunch of pop tunes in the then new hot genre of bossa nova. Harnell decided to bossa up Bart Howard, and it got to Number Fourteen on the Billboard Hot 100:

And so began the grand enlarging of "In Other Words", opening it up for the world beyond 52nd Street. Two years later, Sinatra and Basie found themselves in the studio making their second album, It Might as Well Be Swing, and with Bart Howard on the set list.

Frank knew what he wanted that day. Quincy Jones' arrangement didn't build: It started with the band at full strength, and there they stayed. "I dunno," said the singer, after the run-through. "Up there at the beginning, it sounds a little dense, Q." So Jones told most of the guys to sit out the first bars and leave it to Frank and the rhythm*. Sonny Payne's brushes set the tempo, Basie provides a couple of plinks an octave apart, and there's Sinatra:

Fly Me to the Moon...

And suddenly Bart Howard's sideways cabaret ballad is head on and literal: it flies to the moon, a love song for the space age, a wild ride with a well-stocked bar. Three decades later, in the Nineties, Sinatra did a couple of faux "duet" CDs, in which he recorded his songs solo and Phil Ramone then scrambled around to find supposedly young, supposedly hot acts who could be pasted in to the tracks. For "Fly Me To The Moon", they asked the country singer George Strait, and the strained hipster patter of the intro – George's banter with an absent silent Frank, a Frank who left the studio months earlier, a Frank who's never even heard of George Strait – sums up, in a desperate wannabe-cool kind of way, the transformation of Bart Howard's little cabaret ballad into ultimate lounge:

Hey, Francis, I don't know 'bout you but I could use a break... Maybe a trip or somethin'...

Fly Me To The Moon...

By this time "Fly Me To The Moon" was such a Vegas über-swinger, the overwrought cabaret songstresses defiantly reclaimed the song, putting it back in three-quarter time or crawl tempo. The critic Will Friedwald says the fast and slow versions are really two separate numbers, respectively "Fly Me To The Moon" and "In Other Words". So Bart Howard achieved a rare distinction: the only one-hit songwriter to get two standards out of his one hit.

It was enough. After the Sinatra recording, Howard retired on the song, and dabbled in interior decorating for most of the rest of his life: a modest, dapper man who'd written a tune about not flying to the moon that somehow wound up there. "The first music played on the moon," said Quincy Jones. "I freaked." Sinatra, a favorite of the astronauts, was part of the song's literal lunarization from the beginning: When the astronauts returned to earth, Nasa invited Frank to serve as master of ceremonies for the welcome-home barbecue in Houston in August 1969, with "Fly Me to the Moon" as the surefire showstopper. Here he is on TV just after that moon landing:

In later years, Buzz Aldrin proposed a follow-up song, "Get Your Ass to Mars", which doesn't sound quite Bart Howard's style. But who knows? Had any other nation beaten Nasa to it, they'd have marked the occasion with the "Ode To Joy" or Also Sprach Zarathustra, something grand and formal. But there's something very American about Buzz Aldrin standing on the surface of the moon with his cassette machine: Sinatra "cocksure" in 4/4, with Count Basie and Quincy Jones. The sound of the American century as it broke the bounds of the planet: a Bart Howard song finally playing among the stars.

(*I get asked a lot of questions about our opening theme for The Mark Steyn Show. In fact, for the orchestration of the first few bars, I just did what Frank did. I said to Kevin Amos, "Let's start with brushes, bass, flute - like the Basie band on 'Fly Me to the Moon'." You can't go wrong.)

~The above essay includes material from Mark's obituary of Bart Howard from Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, which can be yours in personally autographed print format direct from SteynOnline (and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing), or in the new expanded eBook edition, which you can be reading within minutes in Kindle, Nook or Kobo - from Barnes & Noble in the US, from Indigo-Chapters in Canada, and from Amazon outlets worldwide.

The Mark Steyn Club is now in its third year. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that thanks to the Steyn Club this site now offers more free content than ever before in our sixteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club - our latest yarn starts this coming week - and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits including not one but two upcoming cruises - not as far as the moon, alas. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.