Welcome to the final installment of our current Tale for Our Time - published in 1903, Erskine Childers' classic The Riddle of the Sands. Thank you so much for your various reactions to this latest radio serialization. Sol, a very convivial shipmate on last year's maiden voyage of the Mark Steyn cruise, has provided a running commentary most evenings, collectively arguing that Childers' own tragic biography is the key to understanding this tale:

The history and background of Childers is crucial for this story. Thank you for including it in the always-superb introduction. This is quite a reveal from the author a few chapters back:

'...for Davies broke down the last barriers of reserve and let me see his whole mind. He loved this girl and he loved his country, two simple passions which for the time absorbed his whole moral capacity. There was no room left for casuistry. To weigh one passion against the other, with the discordant voices of honour and expediency dinning in his ears, had too long involved him in fruitless torture. Both were right; neither could be surrendered. If the facts showed them irreconcilable, tant pis pour les faits. A way must be found to satisfy both or neither.'

Like eschatology and the kind of debate Christopher Hitchens excelled at, there is shockingly low participation in ethical dilemmas. The lately neglected "honour" the narrator speaks of is featured in The Prisoner of Zenda. Childers' life and death takes it beyond that, into the fog.

Honor is a big part of our tales here, Sol - and of effective storytelling in general, which is why the loss of the concept has been fatal for so many of the arts. Childers himself is a fog, unknowable even to those who knew him well at different phases of his life. It is a terrible thing to lose faith in the assumptions one has been raised in: Some people simply shrug off old beliefs; for others, disillusion curdles into a fierce loathing for all that one had just as fiercely loved. In a certain sense, Ireland's old Protestant Ascendancy was a kind of hyper-Englishness, so in Childers' case it was succeeded by an equally hyper anti-Englishness. On the other hand, there were periods in his life in which his beliefs were more nuanced: He wrote The Riddle of the Sands, for example, just after military service in South Africa, where he had been shocked - for the first time - by some of the things done in the name of King and Empire. Boer republicanism was, in fact, quite an influence on Irish Catholic republicanism - although for obvious reasons the Irish tend to downplay that these days, Afrikaners being even more unfashionable to western liberal opinion than Ulster Orangemen.

Be that as it may, Sol is quite right to draw your attention to The Prisoner of Zenda. For The Mark Steyn Club's second birthday we relaunched our Tales of Our Time home page in a redesigned Netflix-style tile format that makes it easier to pick out whatever tickles your fancy - including Zenda and other tales of honor. So far our Timely-Talers seem to like it.

Meanwhile, on to The Riddle of the Sands. As the concluding episode begins, Carruthers and Davies find Dollman is disinclined to come quietly:

'You fools,' he said, 'you confounded meddlesome young idiots; I thought I had done with you. Promise me immunity? Give me till five? By God, I'll give you five minutes to be off to England and be damned to you, or else to be locked up for spies! What the devil do you take me for?'

'A traitor in German service,' said Davies, none too firmly. We were both taken aback by this slashing attack.

'A tr——? You pig-headed young marplots!

Marplot? Now there's a word you don't hear too much these days. Let us go back three hundred years to when the works of Susanna Centlivre, the most successful lady playwright of the eighteenth century, were packing them in at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. Her most popular comedy opened in May 1709 - The Busie Body (or, if you prefer, The Busy Bodie), in which the eponymous busie bodie is a chap who keeps sticking his nose into the amorous affairs of his chums - and, despite only the best intentions, invariably ends up scuttling them. The character's name is Marplot - because he mars the plot for the would-be wooer.

No marring of plots here at Tales for Our Time. Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear me read the conclusion of The Riddle of the Sands simply by clicking here and logging-in. Earlier episodes can be found here.

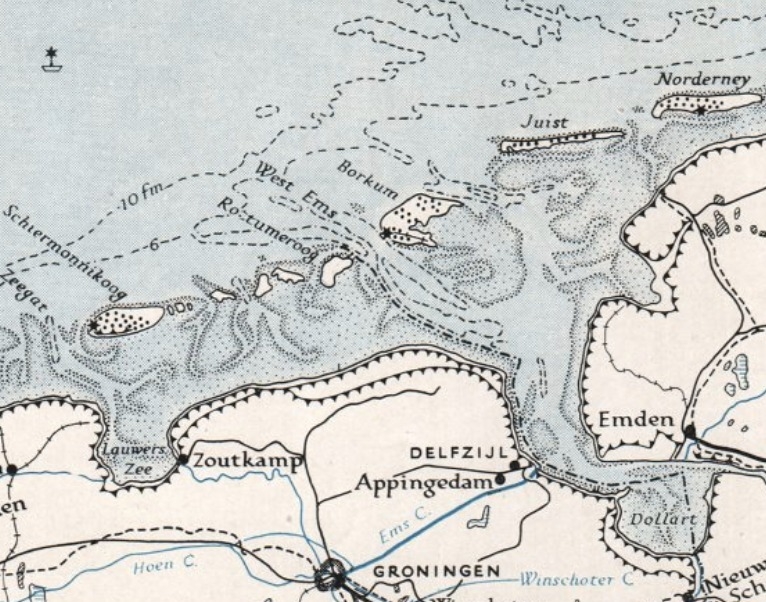

And one final map, showing the Dulcibella's last port of call in this adventure. From Norderney, she heads west to the Dutch Frisian Islands and a "hamlet" so small it's not even marked on most maps - Oostmahorn. It's on the western shore of the Lauwers Zee shown below:

If you enjoyed The Riddle of the Sands, I hope you'll join me later this month for a brand new and very different Tale for Our Time. And, if you've yet to hear any of our Tales, you can enjoy the first two-plus years' worth of audio adventures - by Conan Doyle, Kafka, Conrad, Gogol, Dickens, Baroness Orczy, Jack London, Louisa May Alcott, Robert Louis Stevenson and more - by joining The Mark Steyn Club. For details on membership, see here - and, if you're seeking the perfect present for a fellow fan of classic fiction, don't forget our Steyn Club Gift Membership. Alternatively, if you'd like a book in old-fashioned book form, over at the SteynOnline bookstore there are bargains galore among our Steynamite Special offers.