Happy Independence Day to all our American listeners, whether in the original thirteen colonies, across the fruited plain, or scattered around the world. It may be the Glorious Fourth and a federal holiday, but here at Tales for Our Time the lights stay on. So, if you're in the mood for a break from parades and fireworks, welcome to Part Twenty-One of our latest audio entertainment: The Riddle of the Sands, Erskine Childers' pioneer spy novel set against the long road to the Great War.

That name Childers rang a bell with New South Wales Steyn Club member Rob Mort:

Mark, some useless trivia. Had a few hours in the tractor today, so started listening to The Riddle.

Childers! That piqued my interest. There's a town in Queensland by the name of Childers! It came to notoriety some years ago after the old pub caught fire and several young backpackers who pick fruit in the area, were tragically killed... The town was established in 1885, reportedly named after Hugh Childers, British statesman, who was the Auditor-General of Victoria in the 1850s.

That's right, Rob. As I mentioned in my introduction to Riddle, Hugh Childers was Erskine's cousin: Hugh's father, the Reverend Eardley Childers, and Erskine's father, Robert Caesar Childers (private secretary to the Governor of Ceylon and a distinguished orientalist), were brothers. In 1853 Hugh helped found the University of Melbourne and served as its first vice-chancellor; he was Victoria's Collector of Customs and was elected to the first Legislative Assembly in the state, as the member for Portland. He then returned to England, was elected as the member for Pontefract (in Yorkshire) and held high office in the ministries of Lord Palmerston and Mr Gladstone - Secretary of War, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary - and, which is most relevant to the theme of Riddle of the Sands, a reforming First Lord of the Admiralty.

Hugh Childers was older than his cousin, but even so you could hardly find a man of more different temperament. H C E Childers was a Liberal, and thus supported the party's policy of home rule for Ireland. Erskine liked his famous cousin, but, as a Cambridge undergraduate raised in the Anglo-Irish Protestant ascendancy, he vigorously denounced home rule in many varsity debates. By the early years of the twentieth century, he'd come round to the policy and was actively seeking to follow Hugh and sit in the House of Commons as a Liberal member. Another half-decade on, and he'd quit the Liberals because Irish home rule was no longer sufficient: he was a hardcore Sinn Féin republican revolutionary. Who knows where he'd be had he lived another twenty or thirty years. Hugh Childers is a useful fixed point by which to measure the pendulum swings of his cousin.

One final bit of what Rob calls "useless trivia": H C E Childers put on a lot of weight in later life, and became known as "Here Comes Everybody", which James Joyce used as a character's name in Finnegans Wake - "Here Comes Everybody" or Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, just to tie all this Aussie-Anglo-Irish "useless trivia" together. Tell you what, let's make it Aussie-Anglo-Irish-Canadian trivia: The original illustrations to Finnegans Wake were by my Aunt Stella, who became friends with Joyce in Paris. So I'm the great-nephew of the illustrator of a fictional character based on the nickname of a man commemorated by a town in Queensland. Thanks, Rob! You win today's round of Six Degrees of Erskine Childers.

And on to tonight's episode, which finds Carruthers and Davies battling against time and tide to reach a remote outpost of German intrigue at Memmert:

For an hour we were at the extreme strain, I of physical exertion, he of mental. I could not get into a steady swing, for little checks were constant. My right scull was for ever skidding on mud or weeds, and the backward suck of shoal water clogged our progress. Once we were both of us out in the slime tugging at the dinghy's sides; then in again, blundering on. I found the fog bemusing, lost all idea of time and space, and felt like a senseless marionette kicking and jerking to a mad music without tune or time. The misty form of Davies as he sat with his right arm swinging rhythmically forward and back, was a clockwork figure as mad as myself, but didactic and gibbering in his madness. Then the boathook he wielded with a circular sweep began to take grotesque shapes in my heated fancy; now it was the antenna of a groping insect, now the crank of a cripple's self-propelled perambulator, now the alpenstock of a lunatic mountaineer, who sits in his chair and climbs and climbs to some phantom 'watershed'. At the back of such mind as was left me lodged two insistent thoughts: 'we must hurry on,' 'we are going wrong.' As to the latter, take a link-boy through a London fog and you will experience the same thing: he always goes the way you think is wrong. 'We're rowing back!' I remember shouting to Davies once, having become aware that it was now my left scull which splashed against obstructions. 'Rubbish,' said Davies.

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear Part Twenty-One of our tale simply by clicking here and logging-in. Earlier episodes can be found here.

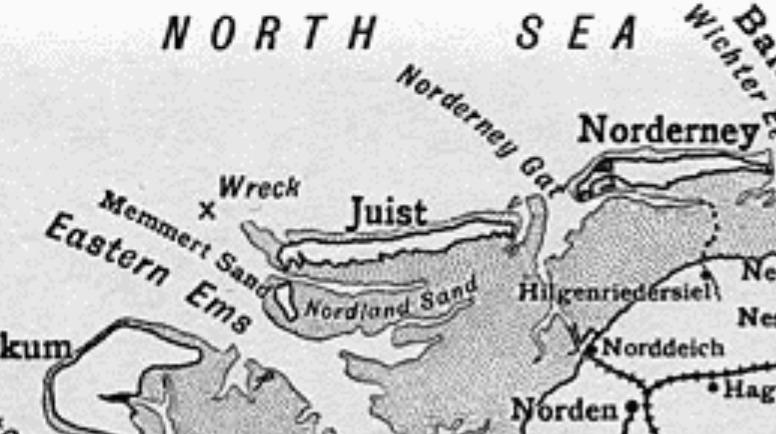

Here's the route of Carruthers and Davies' frenzied race, from Nordeney west to Memmert:

We'll be right back here on Post-Independence Day, Friday evening, with Part Twenty-Two of The Riddle of the Sands. If you're minded to join us in The Mark Steyn Club, you're more than welcome. You can find more information here. And, if you have a chum you think might enjoy Tales for Our Time (so far, we've covered Conan Doyle, H G Wells, Dickens, Conrad, Kipling, Kafka, Gogol, Jack London, Baroness Orczy, Victor Hugo, O Henry, John Buchan, Scott Fitzgerald and more), we have a special Gift Membership.