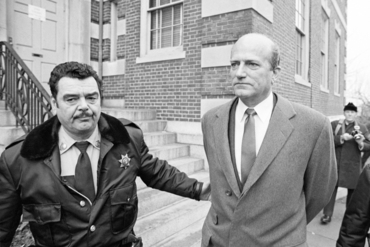

One of the great pleasures of writing for The Spectator (the oldest continuously-published magazine in the English language) is that one never knew by whom one would be upbraided - usually via handwritten notecards forwarded from the Doughty Street office. I think I've mentioned before Sir Alec Guinness' correction of my review of Jane Austen, and John Cleese's likewise about an arcane point concerning the American rights to Fawlty Towers. Still, they're both in showbusiness. It was somewhat stranger to find that among those reading my film reviews was Claus von Bülow, whose only connection to the entertainment world was that he was put on trial for the attempted murder of his wife Sunny (scroll down for Gary Alexander's colleague's joke about "When Sunny Gets Blue"), and afterwards they made a movie about it. My late friend (post-9/11) Ron Silver took the role of von Bülow's lawyer Alan Dershowitz, whereas poor old Claus had the misfortune to be played by Jeremy Irons, and Irons took the easy way out and played him chillingly cold. In fact, as he was wont to complain after the release of Reversal of Fortune, you could say a lot of things about von Bülow, but he wasn't cold. Very gregarious, indeed.

I blame some of his Jeremy Irons problem on his name. He was born in Copenhagen as Claus Borberg, but in Denmark after the war his dad came to be regarded as a Nazi collaborator, so young Claus decided to use his mother's name and became Claus von Bülow, which sounds less like a Nazi collaborator and more like a full-bore Nazi - like a sadistic commandant at Colditz or some such. And, as fate would have it, it's also the perfect name for a guy charged with trying to kill his wife.

Still, he didn't deserve Jeremy Irons.

I had no idea, however, that Herr von Bülow (as I erroneously thought of him) had any interest in motion pictures beyond Reversal of Fortune until I began to receive letters from him nitpicking about various aspects of my film reviews. Here he is from the Speccie's letters page on a film that one would not have thought of any conceivable interest to a Danish socialite living in South Kensington:

From Claus von Bülow

Sir: In his review of Maria Full of Grace (Arts, 26 March) Mark Steyn mentions Colombia and its capital Bogota six times and yet he makes the mistake of saying that the film is about heroin-smuggling. Colombia has no opium harvest and therefore no heroin, but it is the world's largest producer and illegal exporter of cocaine. This is an important factor in US foreign policy and should be of interest to Mr Steyn in his other role as a political columnist.

Claus von Bülow

London SW7

I defer to my correspondent's expertise in matters of narcotics, a subject I find almost as boring as its users.

Claus von Bülow died a few days ago. So, to mark his passing, here's that review of mine of the 2004 film Maria Full of Grace. If this goes down well with readers, we may pick out a few other movies that attracted his gimlet eye over the years:

The publicity poster for Maria Full of Grace shows the face of the eponymous Maria looking up at a hand that's proffering her mouth a vaguely Communion-like pellet. The sacramental imagery, plus the movie title, plus the character's name, plus the fact that she's carrying an unborn baby, and that she works at a rose plantation removing thorns, may lead the casual moviegoer to assume he's in for a religious allegory.

This Maria, from some nowhere town up country in Colombia, is pregnant by her no-account loser boyfriend and the sacramental pellet she's about to receive is, in fact, a baggie of heroin. She's set to swallow 70 of them and get on a plane to New York: she's a courier, or "mule", as they're known in the trade. Hail Mary, full of drugs.

Maria Alvarez is played by Catalina Sandino Moreno, the sort of bright-eyed natural teen beauty every gritty indie slice-of-life needs. You're portraying grinding poverty with dodgy fast-tracks to seedy underworlds — the more typical Colombian country gal in the midst of all that might start off with a more pronounced moustache and wind up quickly with the dead-eyed, pock-marked, hardened-beyond-her-years look of so many bit-players in the drug business. So, if you're trying to communicate the idea of beatific goodness at the heart of a sordid world, the luminous Miss Moreno is just perfect. She made quite a splash at all the hip film festivals, and she deserves the career bump she got, because she's about 85 per cent of the movie.

Joshua Marston, a first-time film-maker, American but directing in Spanish, introduces us to Maria shinning up to the roof of some shack in her village and calling down to the boyfriend to join her. He can't be bothered. He quite fancies a shag, but not if it involves the effort of climbing up the wall: it's that kind of relationship. When she reveals she's carrying their baby, he responds, "You're not f**king with me, are you?" He dutifully if sullenly offers to marry her. "I'm not going anywhere," he says, meaning it in the loyally supportive sense but also pithily summing up his prospects. They bicker in a desultory fashion about whether she'll move into his parents' small house — there's a dozen in the family, and he shares a room with his brother — or whether he'll move into her mother's — which would cast aspersions on his machismo. But neither means it. There's no pretense by either that this child was conceived in love.

Maria wants a better life, better than poverty wages at the rose plantation all day and back to her slack-jawed yokel at night. At a local dance, she meets a fellow from Bogota with the glamorous Yanquified name of Franklin. He knows of a high-paying position that's just opened up. "It's a really cool job," he says. And, with little or no thought, she agrees to become a drugs mule. Seeing her squatting in the bathtub of a New Jersey motel room, attempting to defecate her stomach's valuable cargo for the impatient dealers in the bedroom, I can't say it looked that cool a job. But, for a Colombian 17-year-old, it's certainly lucrative — and in Marston's morally detached presentation we're invited to see it as a rational choice for someone seeking a way out of a life of exploitation for peanuts.

Maria and her friends make it past US Customs at Newark. But, as is the way in the narcotics trade, things go awry, and with violent results. And at this point Maria gets to show what she's made of. Presented with a set of tough challenges, she does the right thing, more or less. But that doesn't exactly justify the title and the film could more plausibly have been called Maria, Full of Spunk: She's a feisty, determined, likable kid, but the religious allegory thing never quite lifts off. The Sixties auteurs who started the mini-genre of finding sacred metaphors among the contemporary world's scuzzy and downtrodden were for the most part conventionally raised Catholics working off the burthens of their childhoods. Marston, by contrast, appears to have no real feeling for the transcendent, but is just seeking a little high-toned gloss for a sweet fable.

Indeed, disinclined to raise Maria's eyes to the Lord or to any saintly vision, the film seeks salvation, intentionally or not, in the American dream: it's New York with all its possibilities that gives the young girl the opportunity to escape both dead-end rural life and the drug cartel. I must be the most stridently pro-Yank film critic in the British press, but for once I found myself slightly irked by the way the film cheers America as the land of plenty without troubling to ponder the fact that it's also the major consumer of the grisly products peddled by Maria and her compatriots.

Oh, well. She's got a lovely face. And the film has some unusual touches, like getting the role of the New York Colombian immigrants' help-center guy played by a real-life Colombian immigrants' help-center guy, Orlando Tobin. And Marston's portrayal of the heroin smugglers as bored schlubs is a lot more plausible than most drug movies.

~As our anniversary observances of The Mark Steyn Club draw to a close, we would like to thank all those First Month Founding Members who've decided to re-re-up for another year - and we hope our second-month members will feel inclined to do likewise as June busts out. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before in its sixteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time (the latest was last Wednesday); it's also an audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have many other benefits, and not one but two upcoming cruises. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we do have a special Gift Membership that makes a great birthday present. More details here.