I'm Gonna Miss You on Valentine's Day

When I see all the young lovers together

I'm Gonna Miss You on Washington's Birthday

'Cause I told a lie and I lost you

I'm gonna feel like an April Fool

When April first is due...

I don't suppose one in a gazillion folks knows the above song. Mel Tormé wrote it, and you get the gist pretty quickly: he's gonna miss you on Valentine's Day, Groundhog Day, Ramadan, Take Your Daughter To Work Day, you name it. The relationship of February 14th to romance is obvious, Washington's Birthday less so, but the dearth of April Fool's songs is more of a puzzler. There are plenty of April songs – "I'll Remember April", "April Love", "April Showers", "April In Paris", "April In Portugal", and a goofy little number from the young Frank Sinatra's days with the Tommy Dorsey band called "April Played The Fiddle"... Yet, in the midst of all this April inventiveness, there's no standard song built around the obvious premise: The word that most easily follows "April" is not "love" or "showers" or "snow" but "fool". And the omission is even more perplexing given that the notion of folly is pretty much built in to the concept of romantic love. As Johnny Mercer put it:

Rube Bloom composed it for ballad tempo, but then Ricky Nelson came and did it somewhat more urgently for the rock'n'roll era - and that's She & Him doing a stripped-down version of the Nelson arrangement that tries for the best of both worlds:

Fools Rush In

Where wise men never go

But wise men never fall in love

So how are they to know?

Very true. Confronted with the sentiments of romantic song, the speech pathologist Wendell Johnson blamed them for what he called the spread of "IFD disease": I for "Idealization (the making of impossible and ideal demands)" leading to F for "Frustration (as the results of the demands not being met)" leading to D for "Demoralization" and a descent "into a symbolic world... The psychiatric profession classifies this retreat as schizophrenia." Expanding on the theme in the 1950s, the semanticist S I Hayakawa attacked love songs for their promotion of "an enormous amount of unrealistic idealization - the creation in one's mind, as the object of love's search, of a dream girl (or dream boy) the fleshly counterpart of which never existed on Earth." Professor Hayakawa deplored the way these irresponsible songwriters give no indication "that, having found the dream-girl or dream-man, one's problems are just beginning." "Disenchantment" and "self-pity" are bound to set in. In the case study he cites, the boy winds up on Skid Row and the girl in a mental institution, all because they believed the love songs they heard on the radio. And yet on the fools rush...

Where wise men never go

But wise men never fall in love

So how are they to know?

It was always interesting to me how often Sinatra would cite that song as the key to what he did. "Take 'Fools Rush In'," he'd say, by way of example. "The story of the song is in the first four lines: 'Fools rush in where wise men never go, but wise men never fall in love, so how are they know?' But most fellows chop it up: 'Fools rush in (breath) where wise men never go (breath) but wise men never fall in love (breath) so how are they to know?' But, if you do it that way, nobody follows the story."

And, whatever the plot, a fool and his love are usually the heart of the narrative. Cole Porter distilled it all into a single question that sums up the entire American songbook:

What Is This Thing Called Love?

- which Musicians' Union wags used to re-punctuate into a honeymoon gag: "What is this thing called, luv?" But Porter meant it for real:

It's a question every songwriter has to answer anew each time he sits down to try and figure out the umpteenth way of saying "I love you". And to his opening question Porter added a couple of follow-ups:

Just who can solve its mystery?

Why should it make a fool of me?

But you can never solve its mystery. As to why it should it make a fool of you, well, why should you be the exception? As Porter observed on another occasion:

Don't you know, little fool?

You never can win...

Porter followed that blunt assessment with one of those unnatural triple rhymes to which he was partial: "Use your mentality/Wake up to reality". "Mentality" ought to sound strained and artificial, but set to Porter's notes (and especially in Nelson Riddle's arrangement for Sinatra) it's the apotheosis of giddy romantic intoxication. The little fool may never win but what a way to go. Who'd want to wake up to reality?

Alas, sometimes you have to. If you want the entire history of popular music on one single - the tug between its highest aspirations and its basest instincts - Sinatra wrapped it up in 1951: On the A side was "Mama Will Bark", a canine love duet that is (as the lyric puts it) "the doggone-est thing you ever heard", performed by Frank and the big-breasted faux-Swede "actress" Dagmar. The early Fifties, don't forget, were the heyday of the dog song, and rare was the pop star who managed to avoid having one inflicted on him: Frank didn't take it well. The Singing Dogs, who barked their way through "Oh, Susanna" and other favorites, were more relaxed about it, but then, of course, they were dogs. By the standards of the era, "How Much Is That Doggie In The Window?" was pretty much Best in Show.

Novelty songs, they used to call them. But, in the early Fifties, novelties weren't so much a novelty as terrifyingly ubiquitous. Mitch Miller, top dog at Columbia Records, insisted Sinatra do "Mama Will Bark". Frank wound up leaving Columbia, but he never forgave his old boss. Years later, they happened to be crossing a Vegas lobby from opposite ends. Miller extended his hand in friendship; Sinatra snarled, "F**k you! Keep walking!"

But Mitch didn't care what went on the B side of the record. So, to accompany "Mama Will Bark", Frank sang one of the bleakest, most harrowing, most exposed ballads he ever recorded:

I'm A Fool To Want You

I'm A Fool To Want You

To want a love that can't be true

A love that's there for others too...

The composer was Joel Herron, who back in 1951 was working on a radio show called "The MGM Theatre Of The Air", a series of weekly audio adaptations of current MGM movies. When it came time to adapt the Katherine Hepburn picture Undercurrent, there was a licensing problem in getting permission to use the film song for the radio version, and so Herron wound up having to rewrite his original movie theme sideways - complete with a point in the tune at which (for plot purposes) a piano lid could be slammed down on somebody's fingers. The rewrite turned out to be superior to the original, especially with Jack Wolf's words:

I'm a fool to hold you

Such a fool to hold you

To seek a kiss not mine alone...

Herron and Wolf took it to Sinatra, then in the midst of his crack-up with Ava Gardner. And Frank got so into the ballad he wound up rewriting enough of the lyric to match his mood that Herron and Wolf cut him in on the royalties. Today, it remains the most widely covered of any song co-written by Sinatra, recorded by everyone from, just to cite the distaff side, Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington to Carly Simon and Linda Ronstadt. Not bad for the B-side to "Mama Will Bark". In the end, "Mama" was the dog that didn't bark, while the flip side has real bite. So here's singer/songwriter Bob Dylan singing a song by singer/songwriter Frank Sinatra:

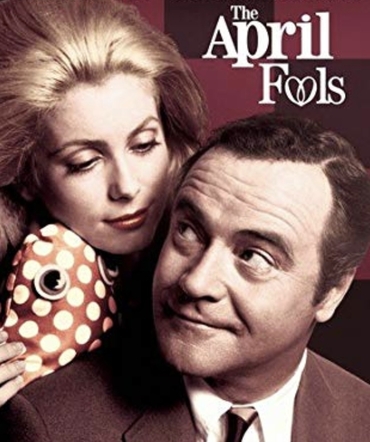

Any of the fools in the above songs – "I'm A Fool To Want You", "Fools Rush In" - could be transferred with little difficulty to an April 1st setting. Yet it doesn't seem to happen. Of the heavyweight songwriters, only three teams (to my knowledge) have had a go at the topic. In 1969, Burt Bacharach and Hal David were asked to do the title song for a movie starring Jack Lemmon, Catherine Deneuve and Peter Lawford. The film was called The April Fools, and thus so was the song:

Are we just April Fools

Who can't see all the danger around us?

If we're just April Fools

I don't care, true love has found us...

It sounds a bit generic movie-theme-y insert-name-of-film-here. Had you interrupted Bacharach and David and said, "Last-minute title change, boys. It's now The Texas Chainsaw Massacre", you get the feeling they'd have replied, "Okay, no problem. Give us ten minutes."

Forty-four years earlier, the young Rodgers and Hart offered their own, singular take on the theme: "April Fool." What a lovely title that would have made for the team in the late Thirties, when Lorenz Hart was meditating on love's illusions in "Spring Is Here" and "Falling In Love With Love". But "April Fool" came at the very dawn of Rodgers and Hart's careers, in 1925, before the landmark hit "Manhattan" had made their reputation. The occasion was The Garrick Gaieties, a revue of topical songs and satirical sketches by a gaggle of young up-and-comers collected together under the banner of "the Theatre Guild Junior Players". "April Fool", an entirely forgotten number, has the distinction of being the first Rodgers and Hart love song in their breakthrough score. It was sung by Romney Brent and Betty Starbuck and took an insouciant view of romantic folly. First, Mr Brent:

My poor heart goes

Anyway the wind blows...

I am burdened with a fondness

For girlish blondness...

Well, there are worse handicaps to labor under. And, so saying, he gets to the nub of the situation:

I must believe in someone

I'm just an April Fool

Doubting may overcome one

Though I'm a dumb one

I'm not a glum one...

That's early Larry Hart for you: a quadruple feminine rhyme – "someone"/"overcome one"/"dumb one"/"glum one". He'd yet to make his reputation as a rhymester. A decade on, he wouldn't have felt the need to be that exhibitionist. Anyway, after Mr Brent, young Betty Starbuck owns up to the same condition:

I like sofas

Full of handsome loafers

Then we play catch-as-catch-can

So my April occupation

Is osculation...

And back to the chorus:

It may rain in April

But I cannot keep cool

And my affection I pour on

Some pretty moron

I'm just an April Fool...

It's lightly-worn romantic folly, but at the Garrick Theatre in 1925 it made a big impression. Conducting the 11-piece orchestra, Richard Rodgers could sense the impact of the song. "Though I couldn't see the people sitting in the dark behind me, I could actually feel the warmth and enthusiasm on the back of my neck," he recalled. "Our show was creating that rare kind of chemistry that produces sparks on both sides of the footlights. What the people were responding to was an irresistible combination of innocence and smartness, two qualities I'm sure helped make 'April Fool' one of the best-received pieces so far." Forty minutes later, Sterling Holloway and June Cochrane introduced "Manhattan", the showstopper that made Rodgers and Hart's names – but "April Fool" laid a lot of the groundwork.

Even so, in this most specialized of sub-genres, I'd have to say my favorite April Fool song is the third of the trio, an obscure ballad by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields:

Once April Fooled Me

With an afternoon so gold, so warm, so beguiling

That I thought the drowsy earth would wake up smiling

But April Fooled Me then

The night was cold...

Where did it come from? Jerome Kern began writing with Dorothy Fields at RKO Pictures in the early Thirties – "Pick Yourself Up", "I Won't Dance", "A Fine Romance". In the teens, Kern had written the prototype American musical comedy songs with P G Wodehouse, and in the Twenties, with Oscar Hammerstein, the great epic of the Broadway stage, Show Boat. But today it's the songs he wrote with Miss Fields that are the most performed tunes in his catalogue, and just about the first thing any recovering rock star does when he decides to make an album of standards is record "The Way You Look Tonight".

Dorothy Fields loved writing with Kern, and in 1945 she talked him back from Hollywood to New York to work on a new musical about Annie Oakley. He and his wife arrived in town on November 2nd and put up at the St Regis.

On Monday morning, November 5th, after leaving a note written in soap on the bathroom mirror reminding Eva Kern of her lunch date with Miss Fields, Jerry decided to spend a few hours shopping for antiques. Waiting for the light at the corner of Park and 57th, he collapsed on the sidewalk. An NYPD officer, Joseph Cribben, called an ambulance and the composer was taken to the City Hospital on Welfare Island. He had no identification other than his membership card in Ascap, the songwriters' and publishers' society. Ascap called Oscar Hammerstein's office, and Hammerstein dashed round to find his old friend in a corridor next to a ward for derelicts. He had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. After moving him to Doctors' Hospital back in Manhattan, Hammerstein, Miss Fields, Eva Kern and their daughter Betty (Mrs Artie Shaw) took rooms nearby and waited. Kern lapsed into a coma, and on November 11th, seated at his bedside, Oscar Hammerstein remembered his old partner's love of their song "I've Told Every Little Star" and lifted the oxygen tent flap and began to sing in his friend's ear. There was, at least by some accounts, a flicker of recognition. It was the last song Jerome Kern ever heard.

Irving Berlin was brought in to replace Kern on the Annie Oakley musical, and Annie Get Your Gun was a blockbuster. But Dorothy Fields was devastated by the loss of her friend. "After he died," she recalled, "his wife Eva sent me a melody - one of his treasures - and I simply had to write a lyric to it." And so Miss Fields provided a posthumous footnote to Jerome Kern's glorious career:

Once someone fooled me

With a kiss that touched my heart beyond all believing

But like April that sweet moment was deceiving...

The tune, like the lyric says, is beguiling, but it's not warm – it's bittersweet, and you can hear in it a regret for what might have been. Dorothy Fields liked it enough to include it in her and-then-I-wrote act but she never really pushed the song much further. And so, if it is one of Kern's "treasures", it remains a private one, to all intents and purposes still hidden from view. But it is a unique song that yokes explicitly the deceptiveness of love and of the first day of April:

It was not really spring nor really love

You were alike, you two

Restless April Fooled Me

Darling, so did you.

Here's to all the romantic fools, on April 1st and every day.

~Mark's book A Song For The Season contains the stories behind many beloved songs from "Auld Lang Syne" to "White Christmas" - and don't forget, when you order through the SteynOnline bookstore, Mark will be happy to autograph it to your loved one. Also: if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, remember to enter your promotional code at checkout to receive special member pricing on that book and over forty other Steyn Store products.

Don't be an April fool and leave it till May to book for the second annual Mark Steyn Club Cruise. We'll be sailing from Vancouver through Alaska's beautiful Inside Passage to Ketchikan and Glacier Bay this September, and, among the attractions, we can promise you a special live-music edition of our Song of the Week. But cabins are going amazingly fast, and, as with most travel plans, the price is more favorable and the accommodations more congenial the earlier you book.

The above-mentioned Mark Steyn Club is now approaching its second birthday. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of it, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.