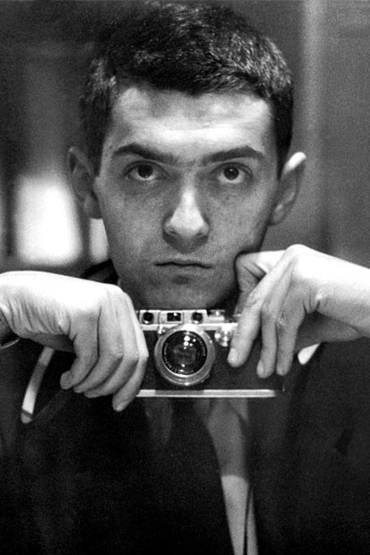

What did the picture editor of Look see in the Bronx teenager's photograph? A weeping city news vendor surrounded by front pages announcing the death of President Roosevelt — and the small, tenderly caught moment that humanizes great events. It got its sixteen-year-old snapper, Stanley Kubrick, a staff job at the magazine, and he never did anything like it again — unless you count the scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in which the computer HAL, the picture's only really human character, gets dismantled in what's easily the most moving death scene in the director's oeuvre.

Stanley Kubrick died two decades ago - March 7th 1999 - with near perfect timing, six days after screening the final cut of Eyes Wide Shut to its stars and his family. Kubrick is an important film maker because he helped establish the definition of the job. In 1950, when he quit Look to sell his first documentary to RKO, a good movie director made as many movies as a bad movie director, it's just that some were better: in 1951 and 1952, for example, Raoul Walsh made eight pictures, which is as many as Kubrick made in his last 37 years. But in those days moviegoing was still a habit: we went to the pictures with little more thought than we now go to the supermarket; if you liked westerns, you saw not just the great ones but the crummy ones, and, if there was no western that week, you saw a thriller. When TV put an end to the routine of weekly flickers, the theory was that the audience would be pickier, choosier, more discriminating. And few directors were better at anticipating the kind of films that a discriminating audience would discriminate in favor of than Stanley Kubrick. Towards the end — which is to say, his last three decades — he nailed the process to a T, advertising the project's importance in the years of preparation, the hundreds of retakes and the groaning weight of its theme, all of which effortlessly flattered the audience's sense of itself. One tiny example: the Peter Sellers gay pick-up scene with the motel clerk, in Kubrick's 1962 Lolita. What's it doing there? It's not in the book, it's nothing to do with the plot, and it doesn't even obliquely contribute to the story's broader environment, its mood and style. Given that Kubrick misses so much of the novel, you can't but wonder how this scene ever wound up in the picture. With hindsight, it's one of the earliest extant cinematic examples of gay chic — and in that, as in so much else, he was way ahead of the game.

One doesn't wish to imply that this is anything so crass as virtue-signaling. To make Lolita, Kubrick had temporarily moved to England - and then hardly ever left. He bought a pad ten minutes from the Elstree studio complex, on Barnets Lane in Borehamwood, where the suburban sprawl of Metroland yields to the occasional quilt patch of green field. I've been to Borehamwood and it's perfectly pleasant, but I don't know whether I'd want to be there to the exclusion of all else. Yet, other than upgrading to an eighteenth-century manor house ten miles north where he produced his films in the converted stables, Kubrick barely went anywhere ever again. He was, in that sense, a compleat film-maker: He lived in his own cinematic imagination, to the exclusion of almost everything else.

He has Peter Sellers to thank for that. After the gay cameo in Lolita, Kubrick wanted Sellers to star in his next film, Dr Strangelove. But Sellers had commitments in the UK, so Kubrick said fine, we'll make it here. He loathed Hollywood and found the crime and violence in New York unsettling, so a Bronx Jew became an English country squire and made films for the world.

Dr Strangelove (1963) planted two phrases in the language — the title and the sub-title, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The quaintly dated Sixties paranoia notwithstanding (from a time when the clouds haunting leftie nightmares were nuclear rather than bovine flatulence), I can testify to their enduring potency: on the very day he died in 1999 The New York Times coincidentally reprinted excerpts of a National Post column of mine in a piece headlined "How Canadians Stopped Worrying and Laughed at a Journalistic Bomb" - complete with an intro referring to "Dr Strangelove scenarios". The film had nothing very useful to say about our nuclear future but it eerily foretold our cinematic one: think of its signature scene — the Armaggedonouttahere mushroom cloud, accompanied on the soundtrack by Vera Lynn singing "We'll Meet Again". Such irony was newish in 1964, although Carl Foreman's dark deployment of "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" in The Victors just predates it. But it quickly established itself - Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange, bawling "Singin' In The Rain" while battering the crap out of his hapless victim - and then became tediously compulsory, with Quentin Tarantino using anodyne Seventies pop to accompany the ear-severing in Reservoir Dogs, and dwindling down from there.

Still, Kubrick appreciated the importance of those moments better than any one: even as his once-a-decade pictures stood loftily above the fray, they were among the first to foretell pop culture's descent into circular self-reference. Think of Jack Nicholson in The Shining (1978), the mad axeman leering Ed McMahon's "Tonight Show" intro - "Heeeeeeeeeeere's Johnny!" For 2001's score, Kubrick was turned down by Carl Orff (bad idea), then went to Alex North (better idea: he did that superb score for Streetcar Named Desire), but ultimately turned to the Strauss boys, Richard and Johann. The director was never one for rock'n'roll and his sex'n'drugs'n'classix approach is, in fact, far more effective: 2001, hailed as the all-time great "head" movie, does indeed approximate the sensation of an LSD or amphetamines experience — a woozy whole but punctuated by just enough moments of piercing intensity that you think, "Wow, man. What a mind-blowing trip." Its most famous sequences, indeed, have a kind of bravura contempt for naturalism: What are we supposed to make of a docking sequence in outer space accompanied not by unobtrusive, dramatically supportive, previously unheard incidental music but by "The Blue Danube"? Pressing into service one of the biggest hits on earth when we're in outer space upturns movie reality: It's not about the "suspension of disbelief" but about the glorious celebration of disbelief. Across a converted stable in the English Home Counties, the horizons roll even unto distant galaxies.

With Clockwork Orange (1971), Kubrick outfoxed himself, accidentally prefiguring new trends not just in cinema but in broader societal nihilism, although the film has to be accounted a poor second to Anthony Burgess's brilliant novel. The talents on display in the heist thriller The Killing (1956) and Kirk Douglas's Spartacus (1960) had by then all but vanished, to the point where these films are barely thought of as Kubrick's at all. The first 45 minutes of Full Metal Jacket (1987) are impressive, even if their remorseless account of the supposed dehumanization of military training could as easily be a metaphor for the director's own working methods. At one point during filming, he asked his cast which of them would like to die early on in the picture: practically every one volunteered.

Many others would go this route, collapsing under the burden of their four-and-a- half-hour director's cuts. But Kubrick was a professional maverick: he rarely lost it. Barry Lyndon (1975), with Ryan O'Neal and various other Seventies period pieces, was a Thackeray adaptation that looked like the manorial life beyond his French windows. But Warner Brothers forgave him and humbly declared themselves honored to pony up the spectacular costs of whatever (if anything) took his fancy. His last film, Eyes Wide Shut, was rumored to be a Wagnerian-scale examination of unprecedentedly explicit scenes of psychoerotica, but it came in under two hours and scraped past the American censors with a commercially viable "R" certificate. According to which reports you credit, Stanley Kubrick either died in his sleep or expired after reading a fax from the brothers Warner congratulating him on a successful screening. As a parting gift, the director tied down Tom Cruise in London for months of shoots and reshoots and re-reshoots, and, if only for keeping the muscular midget off the screen for two years, discriminating moviegoers should all be grateful.

~We can't promise we'll be docking in Glacier Bay to the strains of "The Blue Danube" but we do have the Second Annual Mark Steyn Club Cruise, sailing up the Alaska coast in early September. More details here.