Exactly sixty years ago - in January 1959 - the Platters had the Number One record in America. And exactly 85 years ago - Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra had the Number One record in America. And oddly enough they both did it with the same song:

They asked me how I knew

My true love was true...

Or as the Platters sang it:

The-e-e-ey asked me how I knew...

But never mind how many syllables encrust to a one-syllable word over the decades. In more than one hundred years of American pop charts, "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" is the only song ever to be Number One in the same week in different quarter-centuries. Who knows? If only Lionel Richie or Deniece Williams had thought to cover it in 1984, we might have had a hat trick.

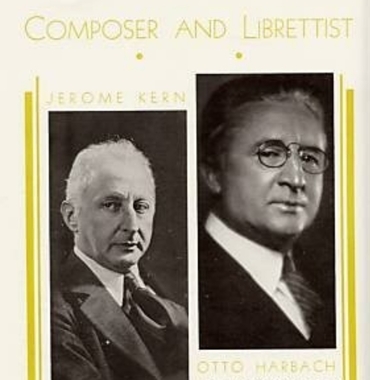

As to which of those two cover versions its composer would have preferred, we'll never know. As detailed in our Song of the Week #93, Jerome Kern died in 1945. So, although he knew the Paul Whiteman record, he never heard the Platters' version. His widow Eva did hear it, however, and loathed it. She felt her husband wouldn't have wanted his songs used for absurdly melodramatic, overwrought rock'n'roll ballads, and so she had her lawyer call the great Max Dreyfus, Kern's publisher at Chappell's, to see about taking out an injunction against the Platters. Mr Dreyfus regretfully had to inform Mrs Kern that, alas, he'd been the one to suggest to Buck Ram, the group's manager (and co-writer of one of the songs on The Mark Steyn Christmas Show, "I'll Be Home For Christmas"), that "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" would be just perfect for them. And unfortunately it looked like the single was on course to sell over a million copies. Mrs Kern decided to forego the injunction:

It was an odd song for 1959. But then it was an odd song for 1934. "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" isn't one of those "timeless" ballads, like "It Had To Be You" or "My Funny Valentine". It sounded old even when it was new. Even 80 years ago, it didn't talk the way pop songs were meant to talk. Consider:

They said someday you'll find

All who love are blind

When your heart's on fire

You must realize

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes

So I chaffed

Them and I gaily laughed...

Whoa, hold up a moment. "Chaffed"? What the hell's that about? Well, chaff, verb transitive: to tease in a good-humored way, from the noun chaff - light jesting talk, banter. Which is probably from chaff, as in the coverings and so forth separated from the seed in threshing grain - ie, surface froth, conversationally speaking, not the real stuff to chew over. Circa 1820s. And it's safe to say pretty much dead a century later.

Yet Otto Harbach sat down in 1933, and put it in a lyric. And, whether or not the Platters had any idea what they were singing about, it remains the only song with any "chaffing" going on in it. Yet it doesn't seem to have been any obstacle to the song's success, and, by the time they got their royalty checks, the Platters were no doubt (as they say in Britain) chuffed to be chaffed.

Incidentally, one of the things I treasure most about SteynOnline are letters like the following. Over a decade ago, writing about the whimsies of Otto Harbach, I mentioned "chaffed" and received this note from AJ Snyders in South Africa, who wrote that "chaff" - pronounced with a long "a" to rhyme with "scarf" - remains part of the language in the small towns to the east and west of Johannesburg:

To 'chaaf the girls' is to flirt with them; 'this is just chaaf-chaaf' means we are just pretending, as in: 'is that just chaaf-chaaf or are you really going to live in Botswana?' The most common use is probably 'I was just chaafing you, man' to mean 'I was just kidding around'. I have no idea where it comes from but the meaning of our 'chaaf' is so close to the one you cite that I doubt they are unrelated.

The person most likely to have used chaff/chaaf in a song is David Kramer, who has sung about moments and events in small-town suburban life.

Hmm. I chaafed a girl and I liked it, as Katy Perry would say.

"Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" has its origins in Kern's masterpiece, his 1927 score for Show Boat. He wrote so much great music for that - not just "Ol' Man River" and "Make Believe" and "Can't Help Lovin' That Man O' Mine", but so many other things that in anybody else's score would have been the highlight. A lot of it fell by the wayside, cut in rehearsal, or during out-of-town tryout. There was simply too much music. "I don't care how good it is," Oscar Hammerstein's son James once told me. "At a certain point, you've had enough and you want to go home." And among the minor casualties was a bit of uptempo fluff he wrote for a tap dance to be performed "in one" - in front of the curtain while they're changing the scenery.

Five years later - 1932 - NBC commissioned Kern to write a weekly series of musicals for radio. He looked over the compensation, said sure, and decided to write a theme tune for the show to get himself in the mood. Well, not exactly "write". Instead, he rummaged around in his trunk, found the discarded scene-change tap dance from Show Boat and retooled it as a march - just the thing for a bigtime radio theme.

But the NBC series never happened, and a year later the composer and his longtime collaborator Otto Harbach found themselves adapting a novel by Alice Duer Miller called Gowns By Roberta. In the teens, Kern had more or less invented American musical comedy in the Princess shows with Guy Bolton and P G Wodehouse. In the Twenties, he'd written the great Broadway epic in Show Boat. In the early Thirties, he was having a tougher time of it, and it's hard to figure what he and his collaborator ever saw in Roberta. The novel begins:

When a man is six feet two, handsome as a god, captain of his college football team, and universal choice for All-American halfback, he cannot burst into tears because a girl is cruel.

Harbach dutifully turned in a tale in which the aforementioned all-American college football god inherits a dress shop in Paris and goes over to run it. He is, inevitably, smitten by the young sales assistant, who is revealed in the finale to be a princess. This is usually good news, as it means she's just been slumming as a shop girl and they can now retire to a palace in Mitteleuropa. Unfortunately, in this variation of the old operetta standby, she turns out to be a Romanov princess, which is no good for anybody, since she's not going to be returning to Russia any time soon, and, if the Commies got wind of her whereabouts, even the dress business might attract more attention than a genial football jock might be game for. But never mind the idiot plot: They had Ray Middleton as the lead, supported by a bunch of up-and-comers: the pre-NBC Bob Hope, the pre-Hollywood Sydney Greenstreet and Fred MacMurray, and the pre-US Senate George Murphy. For the role of the aunt the producer Max Gordon lured out of retirement the great turn-of-the-century Broadway star Fay Templeton. Three decades earlier, as his friend Alan Jay Lerner (author of My Fair Lady) told it to me, Otto Harbach had been taking a street car uptown, passed a giant billboard advertising Miss Templeton in some forthcoming attraction and thought: "I wonder what it would be like to write a musical show." That Fay Templeton poster had prompted Otto to abandon a teaching career and go into showbusiness, and now here they were half a lifetime later working together on a brand new show.

Miss Templeton had just one song, the wonderfully sensuous "Yesterdays", in a score that also included "The Touch Of Your Hand" and "You're Devastating". But one day, as Harbach liked to recount, he happened to be round at Kern's place, and saw an old tune lying on the piano. He asked Jerry to play it, and the composer obliged. The notes that had taken Otto's fancy were short, fast notes: Pom! Pompompompompom - the kind of machine-gun notes you can tap-dance to. Jerry told him the tempo was all wrong for a show like Roberta, but Otto said no, let me hear the short, fast notes again, but this time play them long and slow. And, when he did, the tune emerged as the great ballad that had been there all along, buried in a discarded scene-change instrumental from Show Boat and an unused radio theme for NBC. Harbach went home and wrote to that pom-pompompompompom:

They asked me how I knew...

And followed it with:

...My true love was true

I of course replied

Something here inside

Cannot be denied...

The musicologist Alec Wilder never cared much for the song and sniffed that "it's always on the edge of artiness". Unlike the narrow range of "Yesterdays", "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" ascends an octave in its first few bars as if Kern's itching to get back to operetta and doesn't care who knows it. The melody can easily seem too stiff and formal ever to really flow - at least until you get to the harmonically bold release, which seems less like a middle section and more like a kind of organic growth from the main theme. (The enharmonic change was a device Kern became fond of, and used even more effectively in "All The Things You Are".) As for Harbach, he seems to have responded to the tune's stateliness. Either that, or, at the age of 56, he'd decided to quit pretending he was into the jive talk and just wallow in archaisms. In "Yesterdays", he rhymes the title with "sweet sequestered days" and even throws in a "forsooth". It's as if he's saying, hell, this is the voice I'm writing in, and everyone'll just have to get used to it. Thus the release of "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes":

So I chaffed

Them and I gaily laughed

To think they could doubt my love

Yet today

My love has flown away

I am without my love...

That triple rhyme - "doubt my love/without my love" - is wonderful. And just to emphasize it, in the Platters' version, Tony Williams' backing vocalists immediately bellow:

Without my luuuuuuuuuuuuuuuv!

And then back to Otto's Harbachisms:

Now laughing friends deride

Tears I cannot hide...

Don't you just hate it when laughing friends deride tears you cannot hide? Years ago, at the end of one very late night, a friend and I wandered into the tail end of a revue in which some guy was singing "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" and the rest of the wags were acting out the lyric very literally, and, when they got to the laughing and deriding and started clutching sides and pointing fingers, they brought the house down - and successfully reduced the song to a heap of rubble. On the other hand, over the years I've become rather fond of the emotional floridness. It's a long way from the American pop vernacular, off somewhere in a world of its own, but, if you accept it on its own terms, it can be very sincere and affecting.

For his part, Kern seems to have resented Harbach's claim to have unlocked the song - to have liberated the great ballad trapped in an undistinguished up-tempo instrumental. And throughout the rehearsals for Roberta the composer remained uncertain as to whether the song belonged in the show. For the role of Stephanie, the shop girl cum Russian princess, Max Gordon had found a beautiful Ukrainian called Tamara. The writers insisted that at her audition she perform "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes". So she did. At the end, neither composer nor lyricist said a word to her. After a long pause, she asked nervously if she'd sung it wrong. "Oh, you were all right," said Kern. "We were just wondering about the song."

On November 18th 1933, Roberta opened at the New Amsterdam on Broadway. "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" was the first solo of Act Two, and billed in the program as a "proverb". That's to say, Tamara, as Princess Shop Girl, introduces the song as an old Russian proverb - "When your heart's on fire, smoke gets in your eyes."

Bob Hope ad-libbed a response: "We have a proverb in America: Love is like hash. You have to have confidence in it to enjoy it."

It got a big laugh, but Harbach didn't care for it: He didn't want yuks at that moment; he wanted to set up the song. Tamara sang it very simply, accompanying herself on the guitar. And, when she'd finished, you either got it or you didn't. Among those sitting in the stalls were the conductor Andre Kostelanetz and the critic Robert Simon, and they both agreed that the song was "terrible. It has no future." But outside the show it took off instantly. Paul Whiteman's version, with a vocal by Bob Lawrence, was the Number One, but Emil Coleman and his Riviera Orchestra made Number Four and Ruth Etting Number 15. And chasing Whiteman into the Top Three was Tamara's own recording with Leo Reisman's orchestra. Here's "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" sung by the lady who introduced it, albeit not quite as it was in the show:

The song saved the show. On January 21st 1934, The New York Herald Tribune identified Roberta as the latest example of a Broadway production "profiting immeasurably by a sudden outburst of public whistling, humming and crooning of its score." "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes", the paper reported, "has swept the dance floors, radio studios and glee clubs of the country." Never mind the Platters or Blue Haze or Engelbert, quavery old Bryan Ferry, Gauloise-in-your-eyes Serge Gainsbourg, Zoot from "The Muppet Show", JD Souther in the film Always or any of the later versions, its composer was so picky he couldn't stand any of that first flush of 1930s dance arrangements, and, were it not for the fact that he'd yet to recover from the 1929 crash, he'd have yanked the song from public distribution.

Instead, it became one of his biggest hits, and a kind of farewell to Broadway for both Kern and Harbach. The composer preferred life on the West Coast, and spent the next few years writing movie songs with Dorothy Fields - "The Way You Look Tonight", "Pick Yourself Up", "I Won't Dance". For Harbach, Roberta was the end of a grand run that had begun 25 years earlier with our Song of the Week #100, "Cuddle Up A Little Closer". He was an underrated craftsman: "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" is, after all, a marvelous image, especially in an age when cigarettes bore a lipstick's traces. It was still a potent image for Britons watching TV in the post-Platters era, for whom the song is indelibly linked with Esso Blue, the home-heating paraffin of choice. As the jingle put it:

They asked me how I knew

It was Esso Blue

I of course replied

With lower grades one buys

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes...

I don't suppose Kern would have cared for that, either. But a SteynOnline reader from the Shetland Islands, Chris Smith, had the old flexidisc in which Joe the Esso Blue Man travels round the world accompanied by multilingual versions of the song, and he thought Kern would rather have enjoyed the French version:

Comment est-ce que j'ai su

Que c'était Esso Blue?

Mais au nom de Dieu!

Avec les inférieurs,

Les fumes vont dans vos yeux...

Eight months after getting to Number One, the four male members of the Platters were arrested on August 10th 1959 in a Cincinnatti motel room. The smoke getting in their eyes was from illegal narcotics, and there was evidently so much of it in the air they failed to notice the room had filled up with several prostitutes. It was a catastrophic humiliation, as the public saw the laughing cops deride drugs they could not hide.

Otto Harbach lived until 1963. All but blind, confined to a wheelchair, pushing 90, he told his son Bill right at the end that he'd had a sleepless night because he'd suddenly realized what was wrong with the lyric of "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes".

The fact that the rest of the world had decided thirty years earlier that what was wrong with "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" was precisely nothing didn't matter. Harbach was a perfectionist, a man who sweated over his lyrics to separate the wheat from the chaff, and then figured out a way to work in the chaff. Laughing friends can deride all they want, but, almost a century on, this strange semi-art-song contribution to the American Songbook is here to stay:

So I smile and say

When a lovely flame dies

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes.

~Mark tells the story of many beloved songs - from "Auld Lang Syne" to "White Christmas" via "My Funny Valentine", "Easter Parade" and "Autumn Leaves"- in his book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn store. If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing. And there's many more great songs in our annual Twelfth Night live-music special with Mark and his guests.

If you're in the mood for laughing friends deriding - or deriding friends laughing - come check out Steyn with Dennis Miller together on stage for the first time. They'll be starting their tour next month in Reading, Pennsylvania and Syracuse, New York. And remember that with VIP tickets you not only have the best seats but you also get to meet Dennis and Mark after the show..