On February 18th 2010 Gordon Lightfoot was driving in Toronto en route to the office when he heard on the radio that he'd died. In such circumstances, I think I'd turn round and go back to bed. But Lightfoot kept on, to the office, and to new tour dates and live albums. And so here he is, nine years later, hale and hearty as he celebrates his eightieth birthday having been garlanded with every bauble in the gift of his native land - Commander of the Order of Canada, recipient of the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Medal - and honored by his peers around the world.

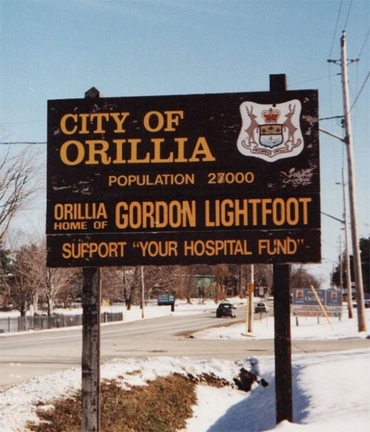

Gordon Meredith Lightfoot Jr was born on November 17th 1938 in Orillia, Ontario, which is a straight shot north of Toronto, although you'll be driving your Honda Civic through Lake Simcoe if you try it as the crow flies. Gordon Lightfoot Sr owned a large dry cleaner's, and Mrs Lightfoot thought Junior had the makings of a child star. His first public solo performance was in Grade Four, over the school's PA system for Parents' Day, singing "Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ral", an early example (1913) of a commercial pop song that everybody thinks is a ancient traditional tune, which isn't bad practice for a chap who'd eventually emerge in the "folk revival" of the early Sixties. He was a boy chorister in Orillia, and by the age of twelve singing in Toronto, at Massey Hall. At eighteen he went to Westlake College of Music in Hollywood to study jazz composition and orchestration, which I can't honestly say I hear a lot of in his music. At any rate, he missed Canada and came home, and landed a spot in the Singing Swinging Eight, the square-dance group on the CBC's "Country Hoedown".

One day a couple of years later Gord thought back to how homesick he'd felt in Los Angeles. So he set down his five-month-old baby in a crib on the other side of the room, and wrote a song about it:

In the Early Morning Rain

With a dollar in my hand

With an aching in my heart

And my pockets full of sand

I'm a long ways from home

And I miss my loved one so

In the Early Morning Rain

With no place to go...

On rainy mornings in Los Angeles, a lonely Lightfoot liked to go to the airport and watch the planes take off. If you try that now at LAX, even if you survive the tasing or shooting, you'll be on the no-fly list for thirty years. But back then it was different, and so a young songwriter wrote, in effect, a train song for the jet age. Just as Johnny Mercer heard the lonesome whistle blowing 'cross the trestle, Gordon Lightfoot heard a wistful echo in the 707s on runway nine:

Hear the mighty engines roar

See the silver wings on high

She's away and westward bound

Far above the clouds she'll fly...

Except, of course, that there's no boxcar on Pan Am or TWA:

You can't jump a jet plane

Like you can a freight train

So I best be on my way

In the Early Morning Rain.

It was on his debut album - the exclamatory Lightfoot! - in 1966, by which time Ian & Sylvia, the Canadian folk act with the arrestingly prosaic name, and the Grateful Dead, the American rock band with the prosaically arresting name, had both recorded the number. And Judy Collins, George Hamilton IV and Peter, Paul and Mary had put it, respectively, on the Billboard album, country and pop charts. "Early Morning Rain" isn't quite the first song Gordon Lightfoot wrote, but it was the first to get any notice internationally, and I do believe to this day it's the most recorded of his compositions. Jerry Lee Lewis did it, and Paul Weller from The Jam, and the Kingston Trio, Eva Cassidy, Billy Bragg... oh, and Bob Dylan, on one of his worst received albums (first line of Greil Marcus' Rolling Stone review: "What is this sh*t?"). It's a simple song, and for my tastes it can go awry in the wrong key or an insufficient travelin' accompaniment. The composer likes Elvis' version, and so do I:

We probably should mention one other take on "Early Morning Rain" - as a marching song for the US Army:

In the Early Morning Rain

With my weapon in my hand

With an aching in my heart

I will make my final stand...

I'm not sure how the author feels about the rewrite, but maybe he could do a Canadian version for the Princess Patricias.

You're probably saying, "Wait a minute. Surely 'If You Could Read My Mind' is the most recorded Gordon Lightfoot song?" Well, it was the first time he cracked the American charts with his own record of a song: The single reached Number Five on the pop chart and Number One on the easy listening chart in 1971. The latter can be more useful than the former, at least in the Seventies. It guaranteed your song an industrial-strength ubiquity on TV variety shows and the like, and meant that, when producers needed Side 2 Track 5 for everybody's album, it was the first thing that popped into their heads: You didn't need to be a mind-reader to read that "If You Could Read Your Mind" was on every A&R man's mind. So Andy Williams and Barbra Streisand and Johnny Mathis and Petula Clark and Herb Alpert and Jack Jones all dutifully recorded the number, which is impressive given that the lyric, written in the ruins of his first marriage, has flashes of rare bitterness:

...I'm just trying to understand

The feelings that you lack

- which these days, at their daughter's behest, Lightfoot sings as "the feelings that we lack". Still and all, it's an unusually vicious line to hear wafting up from the gullets of Johnny Mathis and Pet Clark and Andy Williams, and for me it really needs the writer's own splendidly lugubrious vocal to pull it off. That said, a few years back, when Jessica Martin and I did our spectacular disco version of our Christmas hit, I listened to a lot of disco versions of non-disco songs to get a handle on the feel we wanted. And so it was that I re-acquainted myself with this, from the late Viola Wills:

You can see why all the easy-listening types like it: Lightfoot may have started out among the Judy Collins and Kingston Trio types, but this song is way beyond the verse-and-hook faux-folk of the genre. The tune has three very strong principal themes that arise organically, and without the usual symmetrical lines and tumty-tumty masculine rhymes:

And you won't read that book again

Because the en-

-ding's just too hard to take...

That's what they call a trailing rhyme, Rodgers & Hart stuff. And when we get to the implied feminine rhyme - "I've got to say that I just don't get it" - and you expect it to rhyme with "let it" or "set it" or "pet it", Lightfoot instead offers instead an identity:

And I just can't get it

Back.

And he doesn't rhyme "back" until he gets to those "feelings that you lack" a zillion bars later. Cunning, but absolutely effortless and effective.

By comparison, "Sundown" has an unforgettable hook:

Sundown, you better take care

If I find you've been creepin' round my back stair...

That's memorable and intriguing: Lightfoot came up with it one night after his girlfriend had gone out around sundown, and it was getting late, and she wasn't home yet. And he started brooding on whether, in contrast to the first Mrs Lightfoot, she was so un-lacking in feelings that she was taking them out and spreading them around. And out of that passing paranoia he figured he might as well get a song. And it's a fine conceit, and a dandy tune, except that I can't get beyond the rhymes, which are not just false but tired: "dream"/"means", "pain"/"shame". And I know that doesn't bother the rocky crowd, but I can't help feeling the whole thing would have been better if he'd kept up the precision of the opening couplet:

I can see her lyin' back in her satin dress

In a room where you do what you don't confess...

A few weeks ago, our longtime correspondent in California, Dan Hollombe, to whom I generally defer in matters of boomer rock, gave me a head's up on the impending Lightfoot eightieth observances and added, song-wise, "I can think of many great suggestions, all of them from his United Artists period".

To be honest, aside from Sinatra and one or two others, I don't terribly follow who's on what record label when. And so Dan's qualification drove me to the discography: Lightfoot was on United Artists in the Sixties, and then had all his big hits (like "Sundown") in the Seventies on Reprise. I pulled out, as a great fan of train songs, his "Canadian Railroad Trilogy", written for the Centennial in 1967 but which I've never felt was musically strong enough - although, that said, it's better than anything to come out of Canada's Sesquicentennial, by the time Justin & Co had buggered the whole thing into a national guilt trip. When it comes to trains and boats and planes, Gordon Lightfoot has hymned all three, but it's the middle mode of transportation that produced the song he's proudest of:

The ship was the pride

Of the American side

Coming back from some mill in Wisconsin

As the big freighters go

It was bigger than most

With a crew and good captain well seasoned...

In November 1975 Lightfoot chanced to be reading Newsweek's account of the sinking of a Great Lakes freighter in Canadian waters. He's a slow and painstaking writer, which is one reason he's given up songwriting - because it takes too much time away from his grandkids. But that day forty-three years ago the story literally struck a chord, and he found himself scribbling away, very quickly:

The legend lives on

From the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called Gitche Gumee

The lake, it is said

Never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy...

"Gitche gumee" is Ojibwe for "great sea" - ie, Lake Superior - as you'll know if you've read your Longfellow, which I'm not sure anyone does these days. Evidently Hiawatha was on the curriculum back east across Lake Huron in young Gordy's Orillia schoolhouse. The Gitche Gumee reference may be why, when I first heard "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald", I assumed its subject had sunk long before the song was written. In fact, it sank on November 10th 1975 - just a few days before Lightfoot wrote the number. When she'd launched in 1958, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest ship on the Great Lakes, and, when she passed through the Soo Locks between Lakes Superior and Huron, her size always drew a crowd and her captain was always happy to entertain them with a running commentary over the loudspeakers about her history and many voyages. For seventeen years she ferried taconite ore from Minnesota to the iron works of Detroit, Toledo and the other Great Lakes ports ...until one November evening of severe winds and 35-feet waves:

The wind in the wires

Made a tattle-tale sound

And a wave broke over the railin'

And every man knew

As the captain did too

'Twas the witch of November come stealin'...

And about seventeen miles from Whitefish Bay the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, with the loss of all 29 lives. It remains the largest ship ever wrecked on the Great Lakes, launched in 1958 to take advantage of the new St Lawrence Seaway (to be opened by the Queen and President Eisenhower on an inaugural voyage by the Royal Yacht Britannia the following year) and specifically constructed to be only a foot less than the maximum length permitted. Edmund Fitzgerald was the then chairman of Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance of Milwaukee, and, as far as I'm aware, the only insurance company executive to be immortalized in a song title. Fifteen thousand people showed up for the ship's launch at River Rouge, Michigan. It took Mrs Fitzgerald three attempts to shatter the champers against the bow, and then there was a further half-hour's delay as the shipyard workers tried to loosen the keel blocks. After which the ship flopped into the water, crashed against a pier, and sent up a huge wave to douse the crowd. One spectator promptly had a heart attack and died.

And then came seventeen happy years. Even in the twenty-first century, there is something especially awful and sobering about death at sea: it is in a certain sense a reminder of the fragility of security and modernity. Whenever I'm in, for example, St Pierre et Miquelon, the last remaining territory of French North America, I stop by the monument aux marins disparus, sculpted in 1964 and to which many names have been added in the years since - because a ship put out, and somewhere on the horizon the great primal forces rose up from the depths and snapped it in two like a matchstick.

That said, human tragedy alone does not make for singable material. The last contact from the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was with another ship, the SS Arthur M Anderson. Yet "The Wreck of the Arthur M Anderson" would have been a far less evocative title. Arthur Marvin Anderson was on the board of US Steel, as Edmund Fitzgerald was on the board of Northwestern Mutual. But there is something pleasingly archaic about the latter name: in fact, as I think of it, I believe the last Edmund I met was one of Gordon Lightfoot's fellow Canadian singers - the late operetta baritone Edmund Hockridge. Pair "Edmund" to "Fitzgerald", and you have something redolent of Sir Walter Scott or Robert Louis Stevenson, of shipwrecks off Cornwall or the Hebrides. Perhaps that's why "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" either sounds like an old Scots-Irish folk tune or, alternatively, actually is one. For any IRA members reading this, Bobby Sands, the hunger striker who starved himself to death in a British gaol, wrote in his cell a song called "Back Home in Derry", about Irish prison deportees en route to Australia and set to a tune remarkably like "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald", which it seems unlikely he ever heard.

I see some musicologists claim the tune is in Dorian mode, although it sounds Mixolydian to me (like "The Wexford Carol"). Whichever it is, there is a perfect union between the emphatic melody, the crash of the waves, the antediluvian moniker of Northwestern Mutual's chairman, and even the obvious filler phrases, so typical of ancient folk songs:

The lake, it is said

Never gives up her dead

- which returns far more effectively in the final verse:

Superior, they said

Never gives up her dead

- as if Gitchee Gumee is some vast ravening beast. Go back to Orillia, to Fourth Grade in 1947, and the parents listening to Mr and Mrs Lightfoot's little boy sing "Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ral" as if a bit of synthetic shamrock from an old Tin Pan Alleyman were a genuine Irish lullaby from the mists of Emerald Isle antiquity. That's the genius of "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald": It was born sounding as if it's a hundred years old. And its agelessness is all the more amazing when you consider that it's essentially an act of journalism, an adaptation of a news report about something that happened a few days earlier - just the facts, ma'am, with minimal artistic license:

In a musty old hall

In Detroit they prayed

In the maritime sailors' cathedral...

"Maritime sailors" is surely a redundancy, and it's not a cathedral but the "Mariners' Church", which doesn't quite go the distance syllable-wise. And a parishioner wrote to Lightfoot to say the church isn't in the least bit "musty", so these days he finds alternative adjectives.

But that's all details. The power of the song lies in its storytelling. It immortalized the fate of the freighter not just for the families of the dead, "the wives and the sons and the daughters", but for everyone, and it made the Edmund Fitzgerald the Titanic of the Great Lakes - except that the Titanic never inspired any song like this. The mournful toll of the lakes in the penultimate stanza is Gordon Lightfoot at his very best:

Lake Huron rolls

Superior sings

In the rooms of her ice-water mansion

Old Michigan steams

Like a young man's dreams

The islands and bays are for sportsmen

And farther below

Lake Ontario

Takes in what Lake Erie can send her

And the iron boats go

As the mariners all know

With the gales of November remembered...

The gales of November howl and the waves rise up and devour the ship. And then the gales subside and the placid surface betrays no trace of twenty-nine men, taken deep into the rooms of an ice-water mansion and never to be found. And Superior sings:

~Mark tells the story of many beloved songs - from "Auld Lang Syne" to "White Christmas" via "My Funny Valentine", "Easter Parade" and "Autumn Leaves"- in his book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing.

Speaking of the Steyn Club, Mark will be back later this evening with Part Ten of our current audio adventure, The Scarlet Pimpernel.

The Mark Steyn Club is now into its second year. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of it, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.