On this centenary of the Armistice that ended the bloodiest conflict in history, I have some thoughts on the war that made the world we live in, and the only Sunday Poem we could have chosen for this weekend. But "the war to end all wars" was also a bonanza for Tin Pan Alley. More war songs were written for the First World War than for any other war before or since, and many of them resonate to this day – "Over There", "How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down On The Farm After They've Seen Paree?", "Mademoiselle From Armentières (Hinky-Dinky Parly-Voo)", etc.

The Great War began as the usual kind of war, and so for a while songwriters wrote the usual kind of war songs. About a year after the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo in August 1914, a competition was held in Britain to find "the most morale-boosting song", and two brothers decided to enter. Felix Powell wrote the music, and his brother George (writing under the name "George Asaf") supplied the words. Their song wound up winning, and pretty soon the whole country was singing along:

Pack Up Your Troubles In Your Old Kit Bag,

And smile, smile, smile

While you've a lucifer to light your fag

Smile, boys, that's the style

What's the use of worrying?

It never was worthwhile

So Pack Up Your Troubles In Your Old Kit Bag

And smile, smile, smile!

Not what I'd want to hear as I was marching off to the hell of trench warfare and poison gas on the western front, but chacun à son goût. It was hailed as "the most optimistic song ever written", though by the end of his life its composer found it hard to live up to its hearty injunction. Two decades after "the war to end all wars", Felix Powell found himself serving in its sequel, World War Two, as an old soldier in the Peacehaven Home Guard in Sussex. (For non-UK readers, the home guard were local reserve militias staffed by those too old or infirm to be sent overseas.) In 1942, he put on his uniform, loaded his rifle, and committed suicide.

His fate and that of many others who marched off singing his brother's words gives an unintended poignancy to a lyric that's little more than a cheery title interrupted by what, to American ears, may be a startling image: "A lucifer to light your fag." A "lucifer" was a popular brand of match, and a "fag" remains British slang for "cigarette". Which only doubles the song's sins: It's not just pro-war, it's pro-smoking. But it was a blockbuster worldwide hit in 1915.

Yet it's not the chin-up songs but the ballads I think of – the catchpenny songs of love enlarged by the canvas they're played against. So we have two for you today, starting with the British Tommies' favorite in the hell of 1916, the year of the Somme: "If You Were the Only Girl in the World."

Nat D Ayer was a two-hit wonder, with an ocean between them: "If You Were The Only Girl" was his British hit; his American hit from five years earlier was known to generations of Looney Tunes viewers for most of the next century - "Oh, You Beautiful Doll". This Song of the Week podcast was first broadcast in 2011 to mark the hundredth birthday of "Beautiful Doll" in 2011, with a bit of help not only from Mel Tormé and Al Jolson but also Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Sylvester and Tweety. But after that I talk to Nat Ayer's son, Nat Ayer Jr, about "If You Were The Only Girl In The World", a beloved song of the First World War, and indelibly linked with that conflict through the memories of a generation of soldiers. To listen to this SteynOnline audio special, simply click above.

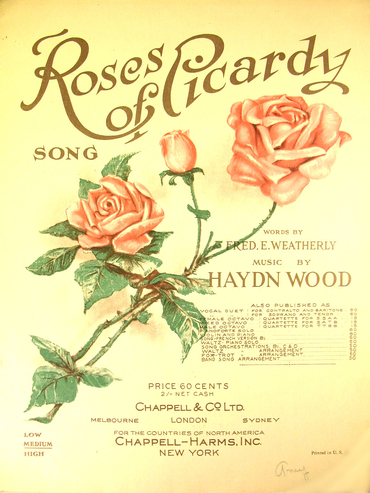

But my very favorite song from the Great War is one I wrote about in my book A Song For The Season, and sang on record in a fairly epic bilingual arrangement with my friend Monique Fauteux. I do believe it's the loveliest song to emerge from the hell of that war:

Roses are shining in Picardy

In the hush of the silver dew

Roses are flow'ring in Picardy

But there's never a rose like you...

It's almost an art song rather than a pop song, yet it's utterly without the stiffness and pretension of so much of the English pseudo-lieder. It's an ethereally perfect union of words and music (with one exception, which we'll come to later), and yet it's muscular enough to work in other ways, too: in the Fifties, Vegas cats like Buddy Greco started doing it as an up-tempo über-swinger with hepped-up whoops interpolated throughout, and, nutty as it sounds, it worked, all the way to the end:

It's the rose that I keep (whoop!)

I see it in my sleep (eek!)

It's the rose that I keep

Locked up in my crazy swingin' knocked-out groovy heart!

You don't get the feeling that Buddy Greco or Bobby Darin are over-exercised by the poignant evocations of the Great War. But, putting such liberty-takers aside, even Count John McCormack, the Irish tenor who had the original hit record on it in 1916, understood implicitly that it was something bigger and more profound than almost all the fragrant Edwardiana to which it harks back.

The authors are Fred Weatherly and Haydn Wood. Weatherly was a successful barrister, a King's Counsel, on the Western Circuit of England's courts, but he dabbled in songwriting, and very successfully. His best-known song is the famous lyric to "The Londonderry Air":

Oh, Danny Boy

The pipes, the pipes are callin'...

The "Air" is one of those traditional tunes that had been around a good half-century before Weatherly got to it and had had many other sets of words appended to it – among them "Emer's Farewell" and "Erin's Apple Blossom", to name but two lyrics by the same guy, Alfred Percival Graves. When "Danny Boy" was published in 1912, Graves, an old friend of Weatherly's, flew into a huff at Fred's impertinence in fixing words to a tune he'd already commandeered. In his splendid autobiography of his musico-barristerial life, Piano and Gown, the lyricist justifies "Danny Boy" this way:

Beautiful as Graves's words are, they do not to my fancy suit the Londonderry air. They seem to have none of the human interest which the melody demands. I am afraid my old friend Graves did not take my explanation in the spirit which I hoped...

Still, Weatherly was right. That's one reason why Piano And Gown, an ancient memoir by a forgotten figure, is worth digging out. Styles of songs may have changed – and had already changed by the time the author wrote his book – but that's still excellent songwriting advice. Any words can be fixed more or less competently to "The Londonderry Air", but "Danny Boy" taps into the essence of the music and articulates it. Even more remarkably, the words weren't written to the tune. Weatherly had never heard "The Londonderry Air" until his sister-in-law sent it to him, and he realized it would make an excellent melody for a poem he happened to have written. A syllable here, a syllable there, and Weatherly had completed the words that now seem so organically tied to that melody, to the point where today it's all but impossible to hear the music of "Londonderry Air" without also conjuring Danny Boy, the pipes, the glens, the sunshine and shadow and all the other marvelous imagery. In a songwriting profession whose British branch was notable for its hacks, the moonlighting KC was a rare talent.

Fred Weatherly was a man in late middle-age when he wrote his two biggest hits – 62 at the time of "Danny Boy", 68 for "Roses Of Picardy". That's unusual, too. Most writers have youthful bursts of energy, a creative peak, and by the time they're in their sixties are either gracefully declining or sputtering very erratically. But, secure in his day job as a lawyer, Weatherly wrote for pleasure and never stopped enjoying it. A former tutor to the King of Siam (Rodgers & Hammerstein could well have written The King And Fred), a friend of Dickens and Gladstone, he serenaded the Queen-Empress herself on Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897. And, although his lasting songs post-date ragtime and early Irving Berlin, they like him have the whiff of the 19th century about them. "Roses Of Picardy" is in some ways the last great Victorian parlor ballad.

When war came in August 1914, his first song, "Bravo, Bristol!", was conventional enough:

It's a rough, rough road we're going

It's a tough, tough job to do

But sure as the wind is blowing

We mean to see it through

Who cares how the guns may thunder

Who recks of the sword and flame

We fight for the sake of England

And the honor of Bristol's name...

It was stirring, but in a somewhat generic sense. "Picardy" came two years in, after the the mud and the slaughter and the knowledge that this would be slogged out a lot longer than Tommy ever thought in 1914. "Picardy" was born as "Danny Boy" was – as words never intended for that tune. In this case, Weatherly had written them to music by Herbert Brewer, a composer and later organist of Gloucester Cathedral. But the publisher rejected the song, and so Weatherly banked the lyric and, a while later, tried again – this time to a tune by Haydn Wood.

There is a story in circulation that Weatherly wrote this after being stationed in France and having an affair with a war widow. Untrue. He was married and in England at the time. But perhaps that testifies to the author's gift for "human interest". After all, the verse sets up a very vivid scenario:

She is watching by the poplars

Colinette with the sea-blue eyes

She is watching and longing and waiting

Where the long white roadway lies

And a song stirs in the silence

As the wind in the boughs above

She listens and starts and trembles

'Tis the first little song of love...

It's not an ostentatious verse but look at the specifics – the poplars, the eyes, the color of the roadway. And over the years I've come to have more respect for its music, too – for the way Haydn Wood sets the first half of the verse on the low notes, freighting the narrative with ambiguity, and the second half on the high notes, as "a song stirs in the silence". The interval on which he puts "si-lence" is eerie and beautiful. There are two verses, and not all singers bother with even one of them. But Sinatra does on his Great Songs From Great Britain album in a ravishing arrangement by Robert Farnon, Canada's all-time greatest orchestrator of popular music. Frank's voice was tired from concerts and Farnon deserved better than the rough timbre on that London session, but boy, is he into the song. You get to the penultimate line of the verse and you, too, listen and start and tremble. What's he going to do with that last bit? Sinatra could easily have rendered "'tis" as "it's". But he doesn't. He sticks with the lyrics as written, and makes the ghostly archaisms of Weatherly's Victorian English very real and true. And then the chorus:

Roses are shining in Picardy

In the hush of the silver dew...

That's one of two spots where the song betrays its age. Haydn Wood set Weatherly's word "silver" on three notes – "si-ilver" – and the melisma intrudes on the scene: its artificiality reminds you that this is a guy singing a song. Most singers of recent decades (though not Sinatra) find a syllable to fill the third note and render it as "in the hush of the silvery dew".

Haydn Wood does it again in the second half of the chorus:

And the roses will die with the summertime,

And our roads may be far apart

- which Wood sets as "fa-ar apart", and which most contemporary singers fill out as "our roads may be so far apart". But these are small easily corrected blemishes on a remarkable song. "Roses Of Picardy" is a First World War "I'll Be Seeing You", a ballad for lovers parted by circumstances beyond their control. It seems like a war song because Picardy is in France and France was where the war was. But, in a lyric of specifics, it's very non-specific about the precise situation. The war is present, but only by implication, and in the ache of the notes on which "flow'ring" is set in that second couplet:

Roses are flow'ring in Picardy

But there's never a rose like you...

Why Picardy? And what's with the roses?

Well, there's no real answer to that. Was it the war? British troops had found themselves in the neighborhood before – there's a pre-Agincourt scene laid near a river in Picardy in Shakespeare's Henry V. But it's hard to believe any war-wounded squaddie shipped back to Blighty in 1916 would be thinking of Picardy in pastoral terms of poplars and long white roadways. According to Gilles Gouset, a great scholar of Haydn Wood's music, in the 19th century the designer William Morris described one of his wall-hanging and chintz patterns as evoking a floral meadow in Picardy in the summer. But, unless he happened to have papered his study with it, it's unlikely that would have prompted Fred Weatherly to write a poem on the subject.

Nevertheless, in France the ballad was accepted as authentically Picardien, to the point where many Continentals are surprised to discover it's actually an English song. A year after its publication in London, Pierre d'Amor wrote a French lyric:

Des roses s'ouvrent en Picardie

Essaimant leurs arômes si doux...

It's a very literal translation, but it has some nice touches: "essaimant" is a lovely poeticism – flowery, one might say. Decades later, a second French lyric was put to the tune, by Eddy Marnay. M Marnay was a highly successful French songwriter, who began his career writing for Edith Piaf and ended it by supplying Céline Dion with most of her francophone hits. But along the way he was sufficiently taken by "Roses Of Picardy" to write a brand new text for the song:

Dire que cet air nous semblait vieillot

Aujourd'hui il me semble nouveau

Et puis surtout c'était toi et moi

Ces deux mots ne vieillissent pas...

I love those words. They translate roughly as:

They say this tune is old-fashioned

Today it seems to me brand new...

And especially, he continues, toi et moi: those are two words that will never grow old. Marnay is, in effect, writing a song about the song, acknowledging that, yes, "Roses de Picardie" is dated but it retains its potency. Yves Montand was one of many French singers who performed the new version – renamed "Dansons la rose" – and he'd always begin by humming along to the music, as if he were an old man recalling across the decades a long-ago love from 1916. On stage, during the instrumental break, Montand would place his arm around the waist of an invisible Colinette and lead her in an imaginary dance. And then, with a wry Gallic chuckle, he'd close with Marnay's beautiful final couplet:

Tous les deux, amoureux, nous avons dansé

Sur les roses de ce temps-là.

"I do not claim to be a 'poet'," said Fred Weatherly. "I don't pretend that my songs are 'literary', but they are 'songs of the people' and that is enough for me. Longfellow expresses better than I can what I mean":

Long, long afterwards in an oak

I found the arrow still unbroke;

And the song from beginning to end,

I found again in the heart of a friend.

Or as Weatherly put it, reworking Longfellow's sentiment:

But there's one rose that dies not in Picardy

'Tis the rose that I keep in my heart.

"Why is it that songs appeal?" mused the King's Counsel. "Is there not a story in each? A melody which remains - deep down in our hearts? We may listen to the noblest sermons. We may study the deepest philosophy. We may be elevated by the loftiest speeches. We may read the brightest pages of history. And yet none appeal to us with quite the same appeal... Song and story appeal to the heart. From the heart they come and to the heart they go."

~adapted from Mark's book A Song For The Season. Mark's epic version of Roses of Picardy with Monique Fauteux, in English and in French, can be found here.