The musician Max Bennett died a few days ago at the grand old age of ninety. He was a magnificent bassist and played with everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to Frank Zappa. But, for the purposes of our Sunday celebration of songs and songwriters, his principal contribution to this department came one night in 1957 when he was playing a date with a jazz trio in a small club on Western Avenue in Hollywood. During a set break they were approached by a chap from the audience who said he was a singer and he'd like to sit in with them. So they said sure, what'd you like to sing? And he replied "Fever."

And they said, "What's that?" So he explained how it went - and, as Max Bennett would tell people in the years that followed, "there's only, like, two chords in it", so it's not that difficult to pick up. So off they went, and the young vocalist started to sing:

You'll never know how much I love you

Never know how much I care

When you put your arms around me

I get a Fever that's so hard to bear...

And, even though Bennett and the boys had never heard of the thing, it went down well with the crowd. So they did it again.

And back home that night he thought of Peggy Lee, in whose rhythm section he'd spent a year playing bass - until she decided she wanted to take a little break from touring. But he remembered that one night, back at her pad, Peg had said to him that she was looking for a "light" torch song. A torch song is one sung by a gal who can't get over a guy, as in the vernacular expression "carrying a torch for someone": Think "Can't Help Lovin' That Man O' Mine", "Guess I'll Hang My Tears Out to Dry" - or come to that, at least in its more smoldering interpretations, P G Wodehouse's "Bill". I'm not entirely sure what a "light" torch song is, since the whole point is that she's got it bad and the burthen of it weighs heavy. Max Bennett wasn't too clear on the concept either, but for some reason he thought this might fit the bill. So he called up Peggy Lee and said he had a song that would be just right for her, and it was called "Fever".

She'd never heard of it either, but she tracked down the publisher, and, unless you've been under a rock these last six decades, you'll know how that worked out. Yet Miss Lee - and most likely you - would never have known of the song had not Max Bennett mentioned it to her, and Max Bennett would never have known of it had not that guy walked into the club he was playing that night. Max never saw the fellow again, and no one knows his name, but we all owe Bennett a great debt for picking up the telephone and dialing Peg. That young man was the vital link between Peggy Lee and Eddie Cooley.

Who?

Well, he was born circa 1930 in Atlanta, and he had a Billboard Top Twenty hit in 1956 with "Priscilla" as the lead singer of Eddie Cooley and the Dimples, the latter being a trio of lady backing singers. Eddie was black but "Priscilla" was less r'n'b than rockabilly-esque, so a lot of white singers picked up on it, including Julius LaRosa and, in Britain, Frankie Vaughan with Wally Stott's orchestra. Aside from singing it, Cooley also wrote it. He liked songwriting, and one day in 1956 he thought he had a pretty good idea and started to work on it, but stalled. So he called up a pal, and said, "Man, I got an idea for a song called 'Fever', but I can't finish it."

The friend was Otis Blackwell, who was on the brink of a terrific run of hits: "Great Balls of Fire" for Jerry Lee Lewis, "Handy Man" for Jimmy Jones, and "Don't Be Cruel", "All Shook Up" and "Return to Sender" for Elvis. Although Otis was happy to give Eddie a hand with the song, at the time he was under an exclusive writing contract to Joe Davis, a fitfully successfully old-time Tin Pan Alley music publisher. Davis wasn't above cutting himself in on songs at the expense of the writers - he did with his biggest success "S'posin'" (which Sinatra liked enough to make two great records of). Blackwell decided not to take any chances and to write it up under the name of his stepfather - "John Davenport". So, with the song finished, it was left to Eddie Cooley to shop around to other publishers:

You give me Fever

When you kiss me

Fever when you hold me tight

Fever in the mornin'

Fever all through the nightListen to me, baby

Hear ev'ry word I say

No one could love you the way I do

'Cause they don't know how to love you my way...

A few weeks later "Fever" was on the stand at a recording session by Little Willie John. Little Willie was a teenage rhythm'n'blues act who'd already had a couple of hits. Eighteen years old and knowing everything, he announced in the studio that "Fever" was a lousy song and he didn't want to record it. The session producer Henry Glover (co-writer of the "Peppermint Twist") called in the label's owner, Syd Nathan of King Records, to lean on the kid and get him to do it. So he did:

Bless my soul, I love you

Take this heart away

Take these arms I'll never use

An' just believe in what my lips have to say:You give me Fever...

It became the title track of the album, and by the summer Little Willie John's single of "Fever" had hit Number One on the r'n'b chart. The orchestration, especially the robotic saxophone, is indifferent, but the voice is authentic and a howl of genuine emotion. Little Willie went on to lead a very fevered life. He liked to drink and had a short temper. In 1963, after a handful of smaller hits with diminishing returns, King Records dropped him. A couple of years later, after a gig in Seattle, he stabbed a guy and was convicted of manslaughter. In 1968, incarcerated in Washington State Penitentiary, he was stricken by a heart attack and died aged thirty.

Aside from affectionate recollections by James Brown and a few others, "Fever" remains his claim to posterity. A while back, listening to my teen daughter's iPhone in the car, I was surprised to find, midst the usual millennial horrors, Little Willie John on her playlist. "Why've you got that on there?" I asked.

"Because you like the Peggy Lee version," she said. I think a similar reasoning explains Little Willie John's presence, in the lower reaches, on lists of Best Records of the Fifties or All-Time Greatest R'n'B Tracks. As with Willie Mae Thornton's "Hound Dog" vis-à-vis Elvis Presley's, there is a cachet attached to the original, at least among a certain school of snooty rock critics. Because Peggy Lee is a pre-rock standards vocalist, her version is carelessly assumed to be the more lavish and produced version, and Little Willie's the more stripped down. In fact, he's got a much bigger band playing a full orchestration, and she's "unplugged" - just bass and very lightly dusted drums.

That was Miss Lee's idea, her arrangement - and, as sometimes happens (Gene Kelly's "Singin' in the Rain", Etta James' "At Last"), the arrangement became the song and supplanted earlier versions. On a panel many years ago, I said that Peggy Lee was pretty much my all-time female singer. To be sure, there were lots of great vocal gals who emerged in the Forties - Doris Day, Dinah Shore, Rosemary Clooney - but she chose better material and sang it like she'd lived it. The composer and musicologist Alec Wilder compared her voice to a streetwalker you'd pass by, but, if you ever stopped, you'd never leave. In Peter Richmond's exhaustive if underwhelming biography (titled, of course Fever), there's a somewhat brusque reminiscence from Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, the authors of "I'm A Woman" and "Is That All There Is?"

Leiber: I loved her. I even loved her big ass.

Stoller: She had much narrower hips at that time.

Actually, that's a not un-useful insight. The other female vocalists who emerged from the big bands were, as Rosie Clooney liked to say, "girl singers". As the song advertised, Peggy Lee was all woman, and not just because she was shoehorned into gowns that exaggerated that hourglass figure: in the Fifties, the poise, the cool, the raised eyebrow and the beauty spot made her as defining an emblem of mid-century pop culture style for the distaff side as Sinatra was for men. She got nearer to him than anybody else did, male or female, in her command of the standard repertoire, in ballad singing and swinging - and she roamed much further than him from the Tin Pan Alley core, recording Chinese poetry and Japanese music (in Japanese).

There was another difference, too. She wrote songs. Not in the occasional sense that a Sinatra or Crosby would wind up with a co-credit on something or other, but seriously and continuously. Indeed, she was one of the first "singer-songwriters", and certainly the first lady one, three decades before Joni Mitchell and Carole King, half-a-century before Sheryl Crow and Madonna. One day, seventysomething years ago, she was pregnant and pottering around doing some housework. "It's a good day," she thought. And the professional in her then had a second thought: "That's a great title." And so it was:

Yes, It's A Good Day

For shinin' your shoes

And It's A Good Day

For losin' your blues

Ev'rything to gain

And nothin' to lose

Yes, It's A Good Day from mornin' till night...

She wrote it up, words and music, and when her husband Dave Barbour – Benny Goodman's guitarist – came home he harmonized the tune and they had a hit. Then she had another idea:

I know a little bit about a lot of things

But I Don't Know Enough About You...

Johnny Mercer liked the premise, and taught her how to work on a title to get the full juice out of it. Peggy Lee had great ideas, and understood singability. If you ever see the clip of The Judy Garland Show with her and Judy singing and kibitzing their way through Peg's "I Love Being Here With You" you'll appreciate what an adroit piece of material it is: in a way that a lot of songs aren't, it's written with performance in mind. There was more to her than that: with Sonny Burke, she wrote the songs for Lady And The Tramp, one of the all-time great Disney scores – not just "He's A Tramp", not just "We Are Siamese", but also that marvelously expansive bit of cod Neapolitana "Bella Notte". She also had a very rare skill of being able to take pieces of essentially unvocal music, put a lyric to them and make 'em stick – "I'm Gonna Go Fishin'", with Duke Ellington, for example, or "So What's New?", one of those insistent Sixties instrumentals Herb Alpert had a smash with and which tickled Miss Lee's fancy so much she wrote a great set of words for it.

I've always liked her songs. Some years back, I had the pleasure of interviewing Peggy Lee – or "Miss Peggy Lee", as her stationery put it - for a BBC series about her songwriting that never got made. Battered by health problems, she was in her Marlon-Brando-in-drag phase then: huge puffy cheeks and big black eyelashes that rendered her eyes entirely invisible, with a wig that sat on her face like half-drawn curtains. What I could see was the trace of a scar on one side of her, from the heavy metal-ended razor-strap her ugly stepmother beat her with during her grim North Dakota childhood. (Heavy make-up covered it in public.) But, speaking or singing, the voice was as sensual as ever. I'd heard that the first lyric she came up with, at the age of four, when her mother died, was something called "Mama's Gone To Dreamland On The Train", and I was crass enough to ask her how the rest of it went. She dodged that one, but she did sing me a few bars of "Bella Notte".

We also talked about arranging. It was Miss Lee who came up with the notion to do Rodgers & Hart's genteely waltzing "Lover" in a driving whiplash arrangement with eight percussionists. It's a magnificent record, and a Lee favorite for a lot of other singers: Petula Clark said a few years back that, for half the world, Peggy Lee is "Fever", but for her Peggy Lee will always be "Lover". Its composer Richard Rodgers was characteristically appreciative of Miss Lee's innovative interpretation: "Why pick on me," he told her, "when you could have f**ked up 'Silent Night'?"

Five years after "Lover", "Fever" required both her arranging and songwriting skills. She liked the finger snaps on the Little Willie John record, but other than that she wanted to start from scratch. First she decided to do it at a light sexy swing for which she required only the sparest of instrumentation. Having determined her general approach, she then concluded that there weren't enough verses and half of the pre-existing ones ("They don't know how to love you my way", "Take these arms I'll never use") had nothing to do with the central thesis - of love as a fever. That's a strong premise, but she didn't feel Cooley and Blackwell had quite got the full juice out of it. So she moved their final verse way upfront as a general statement of the theme:

Sun lights up the daytime

Moon lights up the night

My eyes light up when you call my name

And you know I'm going to treat you rightYou give me Fever...

Even then she made a small improvement: She sang, instead of "my eyes", "I light up" - which is much more fundamental, primal, fevered: her very being lights up. And then she wrote a little transitional passage:

Ev'rybody's got the Fever

That is something you all know

Fever isn't such a new thing

Fever started long ago

- which gave her the excuse to go on a little rummage through history:

Romeo loved Juliet

Juliet she felt the same

When he put his arms around her he said

Julie baby, you're my flame

- which in turn gave her the excuse to do a goofy variation for the chorus:

Thou giveth Fever

When we kisseth

Fever with thy flaming youth

Fever! I'm afire

Fever, yea I burn forsooth...

If you recall Max Bennett's dismissal of the song as "there's only, like, two chords in it", "Fever" isn't the most sophisticated tune, and like all verse-and-chorus numbers it's always at risk of getting a bit predictable, so a lyric variation in this or that chorus doesn't hurt. And besides not a lot of rhythm'n'blues numbers have occasion to deploy the word "forsooth". Actually, not a lot of twentieth-century standards use it - aside from Otto Harbach and Jerome Kern's "Yesterdays".

But by this stage Miss Lee was turning an earthy, vernacular, rough-around-the-edges rhythm'n'blues into a Cole Porter catalogue song:

Captain Smith and Pocahontas

Had a very mad affair

When her Daddy tried to kill him

She said, Daddy, oh don't you dareHe gives me Fever

With his kisses

Fever when he holds me tight

Fever! I'm his missus

Daddy, won't you treat him right?

So the great preponderance of the lyrics of "Fever" were written by Peggy Lee, and almost all subsequent versions have followed her text rather than the original's: Elvis, Joe Cocker, Madonna, Beyoncé... Can you do that? Write a zillion extra verses to another guy's song? Sure - as long as you don't mind not getting paid. I did it myself, for "The Cat Came Back" on Feline Groovy: That song's been around since the 19th century and has acquired a ton of verses, but no version I heard ever provided a real finish to the story, and the song just petered out when the singer felt he'd sung enough verses. So I wrote an ending, and replaced the somewhat cobwebbed Cold War verse with one about Kim Jong-un. But I wouldn't dream of claiming to have "co-written" the thing, any more than Miss Lee did with "Fever": She didn't give herself a writing credit, and she didn't demand a third of the royalties, and, even though it's performed and recorded more than the "Siamese Cat Song" or any other number from her official songwriting catalogue, I doubt that bothered her in the least. (While I'm referencing my cat album, I should add that my version of Ted Nugent's "Cat Scratch Fever" was intended as a sort of hommage to Peggy Lee's non-feline and certainly non-scratchy "Fever".) On the other hand, Little Willie John and Titus Turner both claimed to have written "Fever", even though there's no evidence either man contributed a word or note.

How the original writer feels about having his song rewritten is another matter. As I've mentioned before, Paul Simon fumed to me at some length over Sammy Cahn's rewrite of "Mrs Robinson" for Sinatra, in which Joe DiMaggio et al were supplanted by Rat Pack braggadocio ("So how's your bird, Mrs Robinson..? Mine is fine as wine and I should know, ho-ho-ho"). But, if the original writers of "Fever" were equally enraged over Romeo and Pocahontas, they decided to cry all the way to the bank. Messrs Cooley and Blackwell sat back and enjoyed the ever swelling royalty checks as a modest one-off hit in the summer of '56 gradually became a standard for the post-standards generation. Of the gazillion female vocalists who now feel obliged to give it a go, few really get "Fever". In that sense, it's like all the ghastly retreads of "Santa Baby", stripped of Eartha Kitt's kittenish teasing and sly wit. We should in that respect single out for especial derision Madonna, who has managed to do godawful sexless mechanical versions of both "Santa Baby" and "Fever". In fact, Mrs Krabappel, Bart's schoolmarm in "The Simpsons", was sexier in her version of the latter for the Springfield variety show, dressed only in balloons that she popped on each "Fever!" while Homer & Co looked on in horrified fascination.

Something similar occurred when I chanced to be at Hillsdale College a few years back and the author Will Friedwald was giving a talk on the American songbook. He chose to illustrate his lecture on the versatility of songs with different iterations of "Fever". So he pressed "play" and cranked up Beyoncé's accompanying video, which, alas, is somewhat cruder than Mrs Krabappel's terpsichore. One attendee roared, "I didn't come here to watch pornography, you ass", and another likewise yelled his objections before storming out. Their complaint was that, for a lecture about standards, Mr Friedwald didn't have any. Speaking the following night, I modified the old "I went to a fight and a hockey game broke out" line to "I went to a fight and a beloved easy-listening favorite broke out".

My advice is stick with Miss Lee. The great jazz trombonist Jack Teagarden once said: "When Peggy sings the blues, you're gonna hear the truth." Yet she wasn't a bluesy singer - no wailing like Little Willie, no melismatic histrionics like all the third-rate Aretha imitators who infest the contemporary scene. Peggy is the Count Basie of singers: Lee's is more. And, whatever she had in mind when she first used the expression to Max Bennett, with "Fever" she did indeed create a kind of "light torch" mini-genre: She's got it good, and that ain't bad. I'm not sure what other numbers fall into the category, but maybe one is all you need.

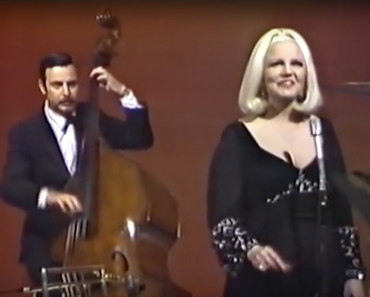

The footnote to this story is that, having brought "Fever" to Miss Lee's attention, Max Bennett then went off on tour with Ella, and thus wasn't available in May 1958 when Peggy went in to the studio at Capitol and recorded "Fever". So it fell to bassist Joe Mondragon, with Shelley Manne on drums, to accompany her on all that burning forsooth. Nevertheless, Max would accompany Peggy on the song innumerable times over the ensuing decades. Here they are on telly in the Sixties, with Jack Sperling on drums:

Boy, I'd love to switch on "The Tonight Show" tonight and see something like that.

One final tip of the hat to Peggy Lee: Remembering what Johnny Mercer had taught her, she put a button on the song. How do you measure fever? With a thermometer. So:

Now you've listened to my story

Here's the point that I have made

Chicks were born to give you fever

Be it Fahrenheit or Centigrade.

As Eddie Cooley said, "I can't finish it" - because sometimes a great work comes by degrees.

~Steyn will be back later this evening for Mark Steyn Club members with Part Ten of our brand new, and especially timely, Tale for Our Time - John Buchan's Greenmantle.

Mark tells the story of many beloved songs - from "Auld Lang Syne" to "White Christmas" via "My Funny Valentine", "Easter Parade" and "Autumn Leaves"- in his book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing.

We'll be essaying a couple of Songs of the Week live and at sea in a week's time on the inaugural Mark Steyn Club Cruise, but alas it is now completely sold out. If you left it too late to book, don't make the same mistake with our next cruise.

The Mark Steyn Club is now into its second year. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of it, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.