Denis Norden was a writer and performer who parlayed an East End boy's love of words and word-play into a seven-decade career. As a writer, he was responsible for the all-time greatest Carry On gag and the makings of a worldwide phenomenon whose latest iteration is playing my nearest multiplex even as I speak. With respect to the former, the interminable Britpic series of cheap'n'cheerful trouser-droppers (second only to 007 in longevity)- Carry On Nurse, Carry On Constable, Carry On Up the Khyber, etc - reached its peak with the moment in Carry On Cleo, when Kenneth Williams as Julius Caesar, betrayed by duplicitous toga turncoats all around him, rages:

Infamy! Infamy! They've all got it in for me...

The screenwriter for Carry On Cleo was Talbot Rothwell. But Rothwell was having difficulty, and one day remembered a gag he'd heard on an old BBC radio show by Denis Norden and his writing partner Frank Muir. So he called up Denis and asked if they'd mind him borrowing it. Denis said, "No problem" - which it wasn't, until Muir and Norden noticed, with mixed feelings, that it kept turning up in polls of the all-time funniest film line - eg, "Infamy infamy is the top one liner."

As a writer, he was unlucky like that. As a performer, he always denied he was one. But his TV show of famous stars' bungles and outtakes was a ratings powerhouse on Britain's top network for three decades. Forty per cent of the population tuned in, and the somewhat jerky Norden mannerisms, the frequent adjustments of his thick black-rimmed spectacles, the slightly nasal voice and the ubiquitous clipboard he carried all became familiar enough to be parodied by TV impressionists and earn him a puppet lookalike on ITV's satirical "Spitting Image". He'd been lunching with a producer in the mid-Seventies and they were laughing about disastrous first takes and actors mangling dialogue when the old light bulb went off and they phoned network honcho Michael Grade, who said, "How soon can I have this?" He gave it a working title of "It'll be Alright on the Night", which Denis thought was no good but promised to fix before launch. He never did.

Showbiz types, being somewhat insecure, were initially resistant to the idea of lifting the curtain on the cutting-room floor, but Peter Sellers loved the idea and had hours of outtakes from the Pink Panther pics he was happy to cough up. And, once he'd done so, Roger Moore, Burt Reynolds et al relaxed and went along. Sellers had strong views on when lifting the veil was appropriate and when not. On his masterpiece, Being There, he was furious to find that Hal Ashby ran an outtake during the closing credits, because he felt it broke the spell of his performance. He complained in vain, and now every third-rate bit of straight-to-video filler does it to ever more contrived effect. Yet Sellers loved his misreadings and corpsing as anthologized on Denis Norden's show. So did his director Blake Edwards, who once told me that was why, after the star's death, he attempted to make a brand new Pink Panther movie assembled entirely from Sellers outtakes. It was very much not alright on the night.

Norden's signature clipboard was a consciously chosen prop, intended to give him the air not of a star turn but merely a jobbing writer who, in his words, "keeps getting wheeled out". Years ago I mentioned to Denis that a BBC producer had been overheard saying "What we need for this show is the new Mark Steyn" (the old Mark Steyn was about 26 at the time), and he replied that the trick to on-air longevity was passing yourself off as a writer who was just doing a bit of performing on the side: That way all the other bitchy presenters never get jealous of you, and none of the twelve-year-old producers and execs can make their bones by showing they have the cojones to fire you. There is a lot of truth in that.

Like all funny men of his generation, he'd been in the war - a wireless operator in the RAF whose commanding officers knew of his comedic bent and let him produce variety shows to keep the chaps' morale up. In the spring of 1945 he was preparing one such entertainment with Eric Sykes in northern Germany and needed some lights. He was told there was a German camp down the road lit up like a Christmas tree, and he could surely find what he needed there. So off he set, and walked straight into Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where, among others, Anne Frank had died a month before. "We hadn't heard a word about it," said Denis.

The camp had been not so much "liberated" as abandoned: The German commandants and Hungarian guards had gone, shooting some of their starving prisoners on the way out and making perfunctory efforts to bury the evidence. Norden and Sykes were greeted by a world of wraiths: you couldn't tell which of these slumped emaciated husks was thirty or seventy, and in some cases alive or dead; wizened starving mothers clutched their shriveled babies, unaware that all life had fled. Denis found some lights, took the jeep back to the RAF, and at base rustled up all the provisions he could find and took it back to Belsen - and, even as he handed it out, worried whether the ruined digestive systems of humans starved to all but death would be able even to handle food.

Then he went back to his comrades and did the show, alright on the night as he always was. It is part of the tedious snobbery of contemporary comedy to sneer at the genial good humor of Norden's generation of funny men. But almost all of them had lived in a reality of horrors unimaginable to those who followed. Today, in an age of micro-aggressions and nano-triggerings, late-night comics who've never seen anything a thousandth as soul-hollowing as the sight that greeted Denis Norden are sour and pinched and joyless in their shtick. When the very name of the comedy divisions of the BBC and ITV - "Light Entertainment" - became a pejorative, Denis remarked, "What's the opposite of light entertainment - heavy entertainment?" We have it today. He once said to me about a famously "edgy" and "transgressive" comic whom we both liked personally: "I find him everything but funny."

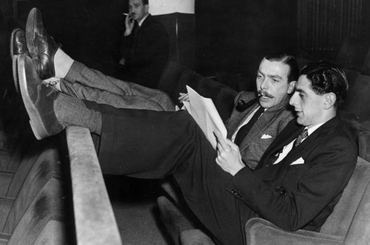

Norden was a Jew from London's old Jewish East End, which is now the new Muslim East End. His lifelong writing partner, Frank Muir, was also an RAF man. Both were tall, but Muir had the whiff of officer class - moustache, patrician drawl, pronounced lisp, and a bow tie. As a child, Denis had memorized the whole of Hamlet, but you could still detect the cadences of Hackney underneath. For decades they were team captains on two mainstays of BBC radio, "My Word" and "My Music", whose critics derided them as twee parlor games but which I think of fondly as literate and civilized entertainments of a kind almost unknown to this century. On the latter, Norden, after his operatic teammates had let rip with art song or aria, would warble some ancient music-hall jest by Weston & Lee. On the former, Muir & Norden would devise arcane flights of fantasy purporting to explain the origins of familiar proverbs - "You can't have your kayak and heat it", "If it ain't baroque, don't fax it", and (as an apology for late arrival due to the vicissitudes of London Transport) "Muir in Surrey, Den in Ongar". Norden loved puns and words and language. I chanced to run into him the day The Guardian published its obituary of Mel Tormé, known to jazz fans the world over as "the Velvet Fog". Denis was still chuckling over a characteristically inept sub-editor who'd headlined the piece "The Velvet Frog" - which is funny because Tormé's features were not un-batrachic. "The Velvet Frog is Sacha Distel," I said.

The jokes lasted. Two Muir & Norden radio catchphrases from the Forties - "Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells", for an eternally outraged Home Counties letter-writer to the papers, and "trouble oop mill", for the inevitable melodramas of gritty northern working-class life - are still known seventy years on, even though the Britain they so deftly encapsulated is wholly vanished. Denis was less fortunate in long form, although his services were sought for many movies over the years: at one end was The Bliss of Mrs Blossom (1968) with Shirley Maclaine and Richard Attenborough; at the other lay Naughty Wives (1973), in which the eponymous missuses take it out of a young door-to-door salesman. Poster line: "What's a woman to do when a handsome man rings her bell?" Movie trailer: "Things start rockin' when he comes a-knockin'." In between, Denis managed to co-write some of the oddest films ever to star, inter alia, David Niven, Robert Vaughn, Virna Lisi, George Sanders, Marty Feldman, Orson Welles and Sharon Tate. All in a writer's life.

Somewhere along the way came a film he wrote with Mel Frank (screenwriter of White Christmas, Mr Blandings Builds His Dream House and a ton of Bob Hope stuff) and Sheldon Keller (from the Dick Van Dyke and Dinah Shore shows). Buona Sera, Mrs Campbell starred Gina Lollobrigida as the eponymous Mrs C, raising her teenage daughter as a single mother in rural Italy. If "Mrs Campbell" doesn't strike you as terribly Italian, well, she's the widow of a US air-force pilot killed in action at the end of the Second World War shortly after fathering their child. In reality, she got the name "Campbell" from a soup can, and has no idea who the father of her daughter is, because at the end of the war she had three brief relationships with three different Americans - Phil Silvers, Peter Lawford, Telly Savalas - all of whom mail her a child-support check from the US each month.

If you're thinking that plot sounds a wee bit familiar, you've probably seen Mamma Mia!, either in the West End, or on Broadway, or on the big screen. A decade after Buona Sera, Mrs Campbell, Burton Lane and Alan Jay Lerner adapted it into a flop musical Carmelina, which was meant to star Paul Sorvino, who talked about it on an episode of The Mark Steyn Show last year. Another two decades on, the plot proved serviceable enough to hold together a couple of dozen Abba songs and kick-start a global blockbuster. I don't suppose Denis Norden ever made a penny from that, but on opening night few others had as much cause to sigh, "Mamma mia, here they go again."

Denis' daughter Maggie Norden gave me my first radio exposure one Sunday afternoon on "Hullabaloo" at Capital Radio in London a zillion years ago. And in my UK days I used to see Denis and his wife Avril (who died just a couple of months ago, after seventy-five years of marriage) at dinner parties with a mutual friend who lived in a flat above the Abbey Road pedestrian crossing made famous by the Beatles. One night with Lionel Bart, composer of Oliver!, the conversation turned to the music you'd like to have for your funeral. And Denis said he wanted the song whose chorus begins:

Beautiful girls

Walk a little slower

When you walk by me...

And we all loved the lines and we all knew the song, but none of us could remember the title. "Sinatra sings it," I said, "and Nat 'King' Cole."

"But what's it called?" asked Denis.

"'Walk A Little Slower'," said Lionel.

"'Beautiful Girls'?" I suggested.

There's a reason none of us knew the title: Gordon Jenkins finished the song and took it to his publisher before realizing he hadn't given it one. So they rummaged around and plucked a line from the introductory verse - "This Is All I Ask" - which not one in ten thousand listeners recognizes. But it's a wonderful ballad about growing old and the consolations of simple pleasures - lingering sunsets, children playing in the park. And, if you had your best-loved joke credited to others, and your best plot borrowed for someone else's hit, and you stumbled into Bergen-Belsen concentration camp expecting to find variety-show lighting, it's not a lot to ask. Rest in peace.

~Steyn will be back later this evening to read the ninth episode of The Mark Steyn Club's latest Tale for Our Time - John Buchan's Greenmantle. For more on Tales for Our Time and other Steyn Club special features, please see here.