In a line much quoted since his death on Thursday, Burt Reynolds observed, "I may not be the best actor in the world, but I'm the best Burt Reynolds in the world." And he was. It made him a huge box-office star in the Seventies, and thus the best Burt Reynolds in the world cruised amiably through Smokey and the Bandit, Cannonball Run and variants thereof for a hugely lucrative decade. He took his bankability and invested it in things he liked - a football team, a petting zoo, and a lovely little theatre in Jupiter, Florida. Squire to an impressive variety of desirable women (Judy Carne, Dinah Shore, Sally Field, Loni Anderson), Burt Reynolds was indisputably the best Burt Reynolds he could be, until various health issues took their toll in recent years. Nevertheless, before he became Burt Reynolds in full but after a long apprenticeship in "Gunsmoke", "Flipper" and far worse, he turned in a pretty terrific acting performance in the 1972 film that made him a bona fide star.

In 1970 the poet James Dickey wrote a first novel about a canoeing trip in the wilds of Georgia that goes awry. The British director John Boorman read it, liked it, and made a film of it two years later, roping in Dickey for the screenplay and a cameo as the sheriff of a condemned rural county about to be buried underwater by a new dam. John Boorman has made several splendid films in the years since; James Dickey went back to poetry and didn't write a second and third novel until half a decade before his death; but neither man ever again planted something in the popular consciousness the way they did with this picture, and its instantly recognizable one-word title. When Pat Buchanan, after trouncing Bob Dole in the 1996 New Hampshire primary, warned the GOP establishment that he was coming to get them like a character out of Deliverance, we all knew what he meant: Deliverance is the film in which some stump-toothed mountain man drags an ill-starred suburban adventurer into the woods and sodomizes the bejasus out of him - and Pat, bless him, in the kind of populist program we can all get behind, was promising to head to Washington and do the same to the RINO squishes.

Knowing about its most famous scene in advance does not diminish a whit one's pleasure in Deliverance, any more than familiarity with all the best lines does to Casablanca or the eponymous dance routine to Singin' in the Rain. Boorman and Dickey begin their tale with terrific economy: Over scenes of the electric company excavating and detonating, Burt Reynolds' character explains to his three fellow Atlanta residents that this is their final chance to spend a weekend riding the rapids of the "Cahulawassee River" before the new dam turns the last wilderness into just another vast, placid lake. Next moment we're deep in the woods where two cars - a jeep and a station wagon, both canoe-laden - are pulling up at a weathered hovel with a gas pump outside.

The quartet are brilliantly cast and swiftly sketched. Two are definitely not the whitewater type: Ed (Ned Beatty) is soft and flabby but cocksure and condescending to the weathered, wizened losers at the fill-up shack, and unconcerned about whether they notice it. Drew (Ronny Cox) is a rangey type (today he'd have a man-bun) who's brought along his guitar to sing pseudo-folk songs round the campfire. The other pair fancy themselves outdoorsmen, but Bobby (Jon Voight), an insurance agent, isn't exactly committed to it: "Let's go down to town and play golf," he suggests to Lewis (Reynolds) while gassing up. But for Lewis the act of canoeing the "Cahulawassee" is a philosophical statement about who he is: "I've never been insured in my life. I don't believe in insurance. There's no risk."

Deliverance begins with one of the most memorable musical sequences in any film. As they're filling up, Drew leans against the car and starts strumming his guitar - and on the porch of the store an inbred dead-eyed albino simpleton repeats each musical phrase on his banjo. And after a leisurely warm-up they take off headlong into what we now know as "Dueling Banjos". The guitarist thinks he's in charge but he gets lost at the end and it's the banjoist who finishes the thing off. "Hot damn, I could play with that boy all day long!" exults Drew. He thinks that music, the universal language, has brought them together and offers his hand. But the kid won't take it, and Drew's bewildered.

Ed's metropolitan condescension is more than returned by the backwoods contempt. So Lewis' offer of forty bucks to a couple of locals to drive their cars to the rendezvous downriver is met with a cool sneer: "Waar yew goan', siddyboy?"

Where are they going? The city boys are about to find out. At a certain level, Deliverance is on a very American theme, of civilization as the thinnest of veneers on something wilder and more primal. One assumes man tames the wilds, but sometimes, as in these dark woods above a foaming torrent, the wilds deprave the man. Three of the quartet like the idea of "the wilderness", but treat it as a kind of theme park: They have brought life-jackets along for the canoes, and they assume likewise that the woods too are similarly safety-compliant.

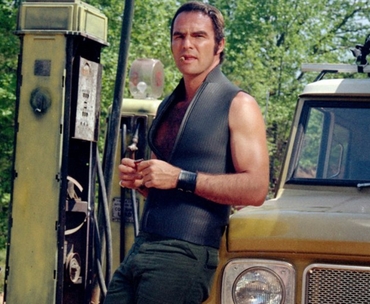

That's not how Burt Reynolds' character reckons, as you can intuit from the moment we first see him in his sleeveless black wetsuit vest designed to show off his muscled arms and the bearskin rug of his chest hair with which, that same year of 1972, Playgirl subscribers would soon become intimately familiar [CORRECTION: Not Playgirl but Cosmo - see Ken B's comment below]. Burt spent much of his career doing a double-act with his pornstache, but in Deliverance, with his upper lip clean-shaven, it's the wetvest that steps into the buddy role. His is not as other men's leisurewear. On that first night round the fire, when the banter is of wet dreams and inflatable broads, Lewis' thoughts are more dystopian: "Machines are gonna fail, system's gonna fail," he muses. "Then it's about survival." And his only problem with that is he'd like it if they just got on with it.

When the system does fail - when two of his buddies are shanghaied by a couple of mountain men, taken to a clearing in the woods, tied to trees and told to drop their pants - Lewis is ready.

Drew is aghast. "You killed somebody!" he says, accusingly.

"That's right. I killed somebody," replies Lewis, and his glee and satisfaction are palpable. Drew, who was once on a jury, can't wrap his head around it - the urge to cast off civilization, and feast in the wild.

Reynolds' performance is magnificent, but he's second-billed to Jon Voight, then coming off Catch-22 and Midnight Cowboy. Voight looks as if he should share the macho confidence of his pal, but his character is a bag of nerves who (as Trump would say) chokes, thrice in the course of the picture - and it's the flabbiest and ostensibly most traumatized of the quartet who is psychologically the strongest. John Boorman's direction, his visual sense, the economical dialogue, the contrast between the great rushing river and the still, brooding woods, all combine for a taut, gripping couple of hours. There is a small scene along the way in which Voight and Beatty find themselves enjoying the hospitality of a rural family who for once are not sodomizers and psychopaths, and the chit-chat is the usual rote bromides about the corn and the peas. It's seemingly unimportant until you see the look on the men's faces, and you come to discern what Drew intuited at that clearing in the woods - that man, once de-civilized, cannot be re-civilized.

~As our second season of The Mark Steyn Club cranks into top gear, we would like to thank all those first-year Founding Members who've decided to sign up for another twelve months - and look forward to welcoming many new members in the weeks ahead. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time; it's also an audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle (you can watch the latest here). We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have many other benefits, and an upcoming cruise from Montreal to Boston at the height of fall foliage season at the end of this month (on which voyage we'll be doing a little Mark at the Movies live at sea). And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership that makes a great birthday present. More details here.