Nicolas Roeg was born in London on August 15th 1928, and on this ninetieth birthday his luster is not quite what one might have expected a few decades back. It's eleven years since he directed his last feature film, and another twelve years since the one before that. It might simply be that there are other things he prefers to do with his time: I forget who it was who argued that the infrequency of novels by Thomas Pynchon (to whom we shall return) is due to nothing other than the improved quality of American television. Yet, notwithstanding the delights of whatever cable package Mr Roeg enjoys in London, it is a melancholy fact that he released more films between 1980 and 1986 than he has in the thirty-two years since.

It was, in fact, the preceding decade - the Seventies - that made him an influence on and an enduring hero to a generation of younger directors, including Christopher Nolan, Danny Boyle, Ridley Scott and Steven Soderbergh. He started as a tea-boy at Marylebone Studios in the Forties, and graduated in the Fifties to camera-loader and husband of starlet Susan Stephen, who was in pretty much continuous employment back then, between The Barretts of Wimpole Street and the simpler charms of Carry On Nurse. In the Sixties, Roeg was a busy cinematographer, on masterpieces like Lawrence of Arabia and leaden fare like the ghastly film of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. He got on with David Lean on Lawrence, but not so well on Doctor Zhivago, from which Lean eventually fired him and had his name removed from the credits. He turned director in 1970 on Performance, with Mick Jagger and James Fox, and followed it a year later with Walkabout.

The latter begins as, say, a conventional thriller or horror movie might - a dad drives his kids deep into the Australian bush, starts shooting at them and then turns the gun on himself. In my school days, it was a perennial favorite with the film society, mainly because lovely Jenny Agutter, last of the English roses, spends much of the picture déshabillé. But it's a cinematographer's movie, and so the dominant character and the real star is the landscape, which has what Louis Nowra correctly called an "almost hallucinogenic intensity". It's not dusty, arid and deserted, but vivid, sharp, blazing, and its impact on the two suburban children is profound. The film is, in that sense, a genuine sensory experience. You don't have to make a movie that way - a story in which people say great lines of dialogue to each other (Casablanca) can be just as satisfying - but Walkabout established what Roeg does best: characters out of their natural environment - an English couple in Don't Look Now, David Bowie as the eponymous Man who Fell to Earth - and are thereby feeling dislocated. And one is by definition dislocated primarily by location: in the Seventies, Roeg conveyed that better than anyone else.

Don't Look Now (1973) took a Daphne du Maurier short story and turned it into something other. Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie are two parents still mourning the death of their daughter and who've taken a job in Venice in hopes of distracting from their grief. It's undoubtedly Roeg's single most influential film: The Venetian finale of the 007 reboot Casino Royale, for example, with Bond haunted by glimpses about town of the elusive Vesper Lind, is a fairly obvious hommage to Roeg. That said, Don't Look Now is most famous for its sex scene, for which across the decades rumors have persisted that Mr Sutherland and Miss Christie were not, ahem, acting. The American censor objected to what he called the "humping", so Roeg went back and re-edited it in his signature style of fragmented chronology - crossing back and forth between the sex and the post-coital dressing and preparing to leave for dinner. In the end, he removed only eleven frames, but it was enough to get it past the censor, and the trick has been much deployed since by other directors.

It also made the picture Roeg's first bona fide box-office smash: In Britain it tied with the boffo trouser-dropper Confessions of a Window Cleaner as the highest-grossing film of the year. Occasionally I speculate on how things might have been if you'd put the Sutherland/Christie sex scene in Confessions and Robin Askwith plus assorted dolly birds in Don't Look Now.

Roeg never again had such a happy confluence of art and cash-flow. But, if you ever find yourself in the presence of Aria, an anthology of one-acts in which ten then fashionable directors (Julien Temple, Derek Jarman) take mostly meretricious cracks at various operatic showstoppers, make sure you stick around for at least the first quarter-hour, in which Roeg sets Verdi's Ballo in maschera to the real-life assassination attempt on King Zog of Albania as he left the opera house one night and gamely thwarted his would-be killers by firing back at them. Roeg cast as King Zog his wife Theresa Russell, who sports the cutest Balkan moustache.

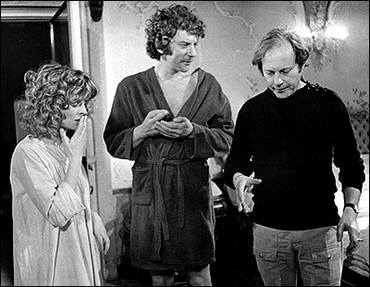

A couple of years after that I spent a day with Roeg and Rowan Atkinson and Anjelica Huston on the set of his adaptation of Roald Dahl's book The Witches. It wasn't to my mind, as a fan of Walkabout and such, an obvious property for the Roeg treatment, but I had a very pleasant time and things seemed to be going well. The Witches opened in 1990 to great reviews, but Dahl disliked the changed ending and so evidently did his fans. It died at the multiplex, and so, for most practical purposes, did Nicolas Roeg as a director in a position to bring his stories to the screen.

As to what might have retrieved his bankability, well, I like to think it would have been me. I was reminded of my own modest connection to the director by a comment from a Mark Steyn Club member, Martin from Down Under, a few days ago:

Twenty years ago you wrote a strongly worded, cogently crafted column... What did it stop? Nothing, in fact things got exponentially worse.

Martin warms to his theme on my general uselessness and impotence. All true, alas. But a chap has to eat, and I lack alternative employment prospects. Yet it wasn't always so. About a quarter-century ago, I got a call from a producer who was making a film about Thomas Pynchon, the publicity-shy novelist who makes J D Salinger look like Kim Kardashian. Or "alleged novelist", I should say, since nobody's seen him since the late Sixties, when he may or may not have come into some fellow's store disguised as a woman (and, alas, not as appealingly transitioned as Theresa as Zog). Anyway, this producer had been looking for a guy to play the lead — a journalist who goes in search of Pynchon — and evidently he'd considered whoever the big male stars were back in the early Nineties — Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis, Burt Reynolds, Don Ameche, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr — but none of them was quite right for what the director had in mind. And then one morning he happened to wake up, switch on the TV and see me on the UK's old Channel 4 breakfast show with Dermot Murnaghan and Joanna Kaye. "Eureka!" he said. Or rather, as he put it to me, "You reek of authenticity. And that's what we need." The producer explained that they were looking for a particular combination of seediness, self-importance and inherent risibility that genuine A-list talent such as Clint Eastwood found very hard to pull off.

He added that Nic Roeg would be directing, and Theresa Russell was about to commit, and it occurred to me, given her energetic track record, that this was probably my best ever shot at landing a Don't Look Now sex scene with Theresa, with or without her cute little King Zog moustache.

So I said yeah, sure, put me down, and a week or so later a script arrived with the working title A Journey In Search Of Thomas Pynchon, whose first scene had me driving a rental car out of the airport in Los Angeles, with Dionne Warwick on the radio singing "Do You Know The Way To San Jose?" as I peered through the window looking for the way to San Jose or someone who knew it. With my name attached to the project, it was evidently rushed through the development process straight to the dust-gathering attic stage. I ran into Nic and Theresa in a restaurant a while later, and deduced from our exchange that they were perhaps not quite as committed to the project as I had been led to believe. But every so often in idle moments late in the afternoon my assistant and I would pull out the script, re-enact my big scenes, and have a grand old laugh.

And there it languished for a decade - until a film called Thomas Pynchon - A Journey Into The Mind Of eventually opened. Instead of Nic Roeg, there were two wacky Italian directors. Instead of Dionne Warwick, there was a trippy electronic score by the Residents. Instead of me — well, I was dreading the shame of being bounced in favor of David Frum or Boris Johnson, but they apparently axed the Steyn role entirely. The movie played London at the ICA art-house on the Mall. With me and Nicolas Roeg, it would have been three months SRO at the Empire, Leicester Square. And that's all I'm going to say.

~As our second season of The Mark Steyn Club cranks into top gear, we would like to thank all those first-year Founding Members who've decided to sign up for another twelve months - and look forward to welcoming many new members in the weeks ahead. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time (we aired our latest edition, live around the planet a few days ago); it's also an audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have many other benefits, and an upcoming cruise from Montreal to Boston at the height of fall foliage season in just a few weeks' time. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership that makes a great birthday present. More details here.