Having been off the scene in recent weeks, I thought I'd catch up with the anniversary of a very unusual standard by the standards of its era. Seventy years ago, this was the big Number One hit that launched the summer of '48 - a strange song by a stranger writer:

There was a boy

A very strange enchanted boy...

Indeed, there was, and his name was eden ahbez. Whether or not he was that enchanted, he was certainly very strange. Mr ahbez eschewed the upper case in his moniker, because he felt capital letters should be reserved for the words God and Infinity. Nonetheless, he was the first lower-case songwriter to get to the upper reaches of the hit parade – just the once, and never again. Not every song is written by an Irving Berlin or Cole Porter, and eden ahbez remains the quintessential one-hit wonder: a single solitary Number One hit that has retained its luster over the decades. On a TV show decades ago, the host asked him: "What is your background? Where did you come from?" And eden replied:

I am a being of Heaven and Earth

Of thunder and lightning

Of rain and wind

Of the galaxies

Of the suns and the stars

And the void through which they travel

The essence of nature

Eternal, divine that all men seek to know to hear

Known as the great illusion time,

And the all-prevailing atmosphere.

"And now you know my background," he added.

Actually, he was from Brooklyn.

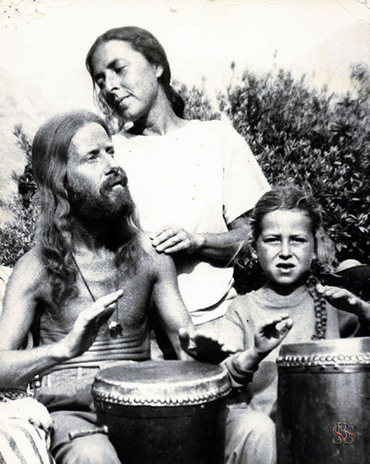

eden ahbez was born on April 15th 1908, and did nothing in particular until seven o'clock one morning in 1946 when he turned up at the stage door of the Million Dollar Theatre in Los Angeles. The doorman thought he was a "goofy-looking guy" – he was wearing robes and open-toed sandals, and he had a full beard and long, long strawberry-blondish hair hanging way down his back. He looked like a prototype hippie, though this was two decades before the summer of love. Alternatively, he appeared to be affecting a Christ-like garb and demeanor, which was also odd, given that he was, by some accounts, born a Jew. His name back then was George Alexander Aberle, one of 13 children. He spent his early years in an orphanage before being adopted by a Kansas family and raised under the name George McGrew. He claimed to have crossed the country eight times on foot by the age of 35, and we pretty much have to take his word for it because nobody really knows. But in 1941 he showed up in Los Angeles and got taken on as a dishwasher at the Eutropheon, a raw food restaurant run by John and Vera Richter, a German couple who espoused the "naturmensch" philosophy and whose followers were known as – wait for it – "nature boys". And, as far as we know, that's the only deployment of the phrase until eden ahbez's song planted it in the language for once and for all. ahbe (as he was known to his friends) was more nature-minded than most of the boys: He married a woman called Anna Jacobsen and they shared a sleeping bag in Griffith Park. Their only real possession was a juicer.

Somewhere along the way, amid all the wandering down dusty roads and hopping box cars, ahbe picked up veganism and Eastern philosophy ...and a song. As his sister-in-law put it, "He absorbed the echoes of the life around him. He wrote a poem from those echoes. And music from those echoes":

There was a boy

A very strange enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far

Very far

Over land and sea

A little shy

And sad of eye

But very wise was he...

And that was how he came to be standing at the door of the Million Dollar Theatre. Among the customers of the Eutropheon was Cowboy Jack Patton, who'd had a western swing band called Pals o' the Range and done a couple of movies before landing his own radio show. It was vegetarianism that brought Cowboy Jack and eden ahbez together. Patton had his own health food store but he liked the salads at the Eutropheon, and chanced to be there the night the Richters let their dishwasher play the piano. Thereafter, Cowboy Jack took to dropping by for ahbe's weekly tinkle of the ivories, and, when he heard the song his friend had "absorbed" from "the echoes", he suggested taking it to Nat "King" Cole. Nat had had a small role in the film Swing In The Saddle, which included Patton's song "Cowboy's Polka".

So at the Million Dollar Theatre eden ahbez asked the doorman if he could see Cole's manager, Mort Ruby. "I'm busy," Ruby said. "Whatever he has to say he can tell you." So a few minutes later the doorman came back with the message that the "goofy-looking guy" had written a song for Nat. "Aw, please," Ruby said. "Tell the guy to get lost." In those days everyone was a songwriter and every songwriter had a song for Nat. One composer had even followed Cole into the men's room and insisted on demonstrating his song while the singer was, as it were, a captive audience. Nat's manager had had his fill of budding songsmiths, and so quickly forgot about the goofy-looking guy at the door.

But returning to the theatre the following morning, Mort Ruby was stopped by a short fellow in sandals, rags and long unkempt hair who handed him a tatty piece of sheet music marked "Nature Boy". "I want you to give this to Nat," said ahbez. "All right," replied Ruby. "I'll see what I can do." He went up to the star's dressing room and dropped the sheet on the table, saying. "Here's another one for the collection." Cole didn't pick it up. His only comment was about the grubbiness of the manuscript.

A few nights later, Nat said to his manager, "You know, Mort, you've been talking to me about doing a Jewish-sounding song... Well, I think I've found one." And he held up the dingy music sheet, and started to sing:

There was a boy

A very strange enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far

Very far

Over land and sea...

What did Cole and Ruby mean by "a Jewish-sounding song"? eden ahbez wrote "Nature Boy" in E minor, and the whole thing has a minor tonality, and the chromatic descents in the second phrase ("Very far, very far, over land and sea") and again in the latter half ("many things, fools and kings...") could certainly sound Jewish in the right context - or Jewish enough for pop music (like, say, Al Jolson's then new "Anniversary Song"). "What do you think?" Cole asked Ruby.

The manager wasn't sure. "Don't you think the lyric is a little far out?" Actually, the "far out" lyric fits perfectly the "Jewish-sounding" tune:

A little shy

And sad of eye

But very wise was he...

The altered pitch on that "very wise" and again at the end ("the greatest thing you'll ever learn") give the song an other-worldly quality: You couldn't sing about taking your best girl dancing to that music. So the words have to go "a little far out" just to keep up with the tune.

But Nat took his manager's point. So he put away the manuscript. After a few days, eden ahbez returned to the theatre, and could find nobody except Cole's valet. He promised him 50 per cent of the royalties if he could persuade the singer to use the song. As it turned out, he'd already promised 50 per cent of the royalties to a dozen other people he'd run into.

A little later, the King Cole Trio opened at a nightclub in Hollywood. Among the audience was Irving Berlin and Nat decided to finish his set with the song on the grubby manuscript. Before he'd reached his dressing-room, Berlin, not only America's top songwriter but a shrewd music publisher of the works of others, had buttonholed Nat and offered to buy the song. "I can't sell it," replied Cole. "I don't know anything about it. I don't even know where the guy is who brought it to me."

Still, Berlin's reaction had convinced him that he must record it, so the King Cole Trio went into the Capitol studios and laid down a track. They junked the waltz tempo in which ahbez had conceived it and performed it colla voce as an intense ballad:

And then one day

A magic day he passed my way

And while we spoke of many things

Fools and kings

This he said to me...

After the first take, the producer said: "This'll be the biggest piece of subtle material ever. We've got to release this." So it wasn't so "far out" after all; in Nat's hands, it had come back in to the more potentially appealing territory of "subtle".

If the material was subtle, its author was all but undetectable. To release the song, Capitol had to get permission from the man who wrote it, and all Mort Ruby knew about him was that he was called eden ahbez. He phoned every music publisher in town; he tried the musicians' union. But nobody had ever heard of him. Then he got a lead: Yes, there was an eden ahbez - he was a practicing yogi, who slept rough somewhere up in the Hollywood hills, but during the day he sometimes hung around the corner of Sunset and Vine. So Mort Ruby went and hung around Sunset and Vine. No sign of ahbez. So he went to the police.

"Sure we know him," said one of the officers. A while back, ahbez had been stopped by a cop who figured from the shoulder-length hair – this was 1946, remember – that the guy was a nut who'd escaped from the asylum. ahbe told him calmly, "I look crazy, but I'm not. Other people don't look crazy, but they are." The officer chewed that one over and eventually replied, "You know, bud, you're right. If anybody gives you any trouble, let me know." When Mort Ruby made his enquiries, the police told him ahbez didn't stay anywhere too long, but you might find him up on the hill under one of the 'L's in the 'HOLLYWOOD' sign." So Ruby clambered up to the famous sign, and there under the first "L" he found eden ahbez asleep. When he woke up, the songwriter didn't recognize Cole's manager. He'd forgotten him completely.

By the time Mort Ruby had a deal on the song, Capitol Records had decided the lyric really was too far out. And that was that, until August 12th 1947, when, at the end of a recording session with a full orchestra and with a few minutes to spare, Cole suggested that they should try the ahbez number. In March 1948 Capitol issued the song "Lost April", with "Nature Boy" as the B side. By now, there was a rumor in the music business that Nat Cole had one of the greatest songs ever up his sleeve. The first disc jockey to receive the record was Jerry Marshall at New York's WNEW. He listened to "Lost April", shrugged, and decided to play the flip side. On March 22nd 1948, at 2.16pm, on WNEW's "Music Hall", Marshall introduced the record with the words:

Here's a winner - a song everybody is going to love.

By 2.20pm the phone calls were flooding into the station. Within a few weeks, while Nat and Maria Cole were on their honeymoon, the song was America's Number One, a million-seller and a phenomenon. As The New York Age reported:

On 42nd Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, for instance, the record shops play this number constantly, over and over again. Great crowds gather, some hearing it for the umpteenth time, others just getting to know about it. Many of them head straight inside to buy it. We think that it is an important artistic success and we couldn't help beaming with pride, inside, to hear some of the comments: 'That feller, King Cole, he's colored, ain't he?'

Yep, he is. And though the white boys – Dick Haymes and Frank Sinatra – rushed out cover versions, "Nature Boy" was the song that introduced mainstream audiences to a new Nat Cole - not the purveyor of goofy rhythm numbers for the trio like "Straighten Up and Fly Right", but the smooth balladeer of "Mona Lisa" and "Unforgettable". According to Mrs Cole, the public saw "Nature Boy" "as the answer to the world's quest for peace and happiness". Others thought that it was successful because the lyric was so obscure it could mean anything to anybody. When ahbez got his first royalty check for $30,000, he didn't know what to do with it. "Maybe someday I will have some use for it," he said. "You see, I don't need money at all. I live on three dollars a week. That's what it costs me for my vegetables, fruits and nuts."

It was just as well he didn't need the money. Herman Yablokoff, a pillar of the Yiddish musical theatre scene on New York's Second Avenue, said that the melody to "Nature Boy" was lifted from his song "Shvayg mayn harts" ("Be Still, My Heart"). ahbez responded that he had "heard the tune in the mist of the California mountains", but Yablokoff countered that the old hippie mystic had picked up on it back when he was living in New York. There was a substantial out-of-court settlement. Hard to see why. The traditional defense in music plagiarism suits is to insist you didn't steal the tune from the plaintiff but from some earlier out-of-copyright work. Both "Nature Boy" and "Shvayg mayn harts" bear a marked resemblance to passages from Dvorak's Piano Quintet No 2 from 1887.

ahbez wrote some more songs for Cole, including "Land Of Love", which Doris Day and the Ink Spots picked up on. It did nothing. He wrote "The Song Of Mating" and a "Nature Boy" suite. They went nowhere. In the late Fifties, he dabbled in rock'n'roll novelty numbers and made Eden's Island, an album of stereotypical beat poetry recited over an orchestra playing sub-Martin Denny jungle exotica. In the Sixties, he briefly surfaced in the company of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson shortly before they made Pet Sounds. I described eben ahbez as a one-hit wonder, but that's not technically true. His song "Lonely Island", recorded by Sam Cooke, skimmed the lower end of the Top 40 in 1957. And that was it.

But "Nature Boy" got bigger and bigger. Ella Fitzgerald and Joe Pass did it, and John Coltrane, and Bobby Darin, and Stephane Grappelli, Marvin Gaye, Grace Slick, José Feliciano, George Benson... It became a standard for folks who didn't like standards. Cher recorded it as a tribute to her late ex-, Sonny Bono. It was the song that held together the "score" of the film Moulin Rouge. Céline Dion made it a pillar of her Vegas spectacular, A New Day, in a performance that would have horrified ahbez: He'd taken the song to Nat Cole all those years ago because he liked the "gentleness" of Cole's voice. Still, by his final years, he didn't much care for the original version either. Returned to obscurity and living in the California desert, he was befriended by Joe Romersa, a drummer and sound engineer, to whom he confided his dissatisfaction with the song's ending:

The greatest thing

You'll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return.

He told Romersa "it was close", but based on what he'd experienced since then, he'd changed the ending to:

The greatest thing

You'll ever learn

Is to love and be loved

Just to love and be loved.

"To be loved in return is too much of a deal," he said, "and there is no deal in love." He'd rewritten the melody to accommodate the somewhat clunkier lyric.

No, no, no. You can understand why the guy only had one hit. It's the precision of the rhyme that redeems it from just being the usual fey hippie-dippie maunderings, that give "Nature Boy" its strange combination of formality and other-worldliness. The rewrite wrecks that. And, even if made aware of the modification, I doubt any of its 21st-century interpreters, from Harry Connick Jr to David Bowie, would have bothered using it.

Oh, well. ahbez lost his wife Anna, for whom he wrote "Nature Girl", to leukemia in 1963, and their son Zoma in 1970. A nature boy in winter, he faded into a spaced-out white-bearded flute-playing Methuselah, still writing poems and music and this and that until he was hit by a car and died of his injuries in 1995. Did America's first lower-case songwriter mind that the "L" in that "HOLLYWOOD" sign he lived under was a capital letter in an all-capitalized word? Who knows? But on its seventieth anniversary his one lasting contribution to the American songbook remains a hit with a capital H.

~Mark tells the story of many beloved songs - from "Auld Lang Syne" to "White Christmas" - in his book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing.

The Mark Steyn Club is now into its second year. We thank all of our first-year Founding Members who've decided to re-up for another twelve months, and hope that fans of our musical content here at SteynOnline will want to do the same in the days ahead. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club, and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits including an upcoming cruise, including a special live seaboard edition of our Song of the Week. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.