I had no intention of watching Gilda.

Winter afternoon sunsets still feel like an affront. How can this be happening? I wonder stupidly for the ten-thousandth time in my half-century life. That night, I especially craved an old movie to curl up with — a celluloid cocktail; an LCD fireplace — after a particularly long, hectic (and now dark) day.

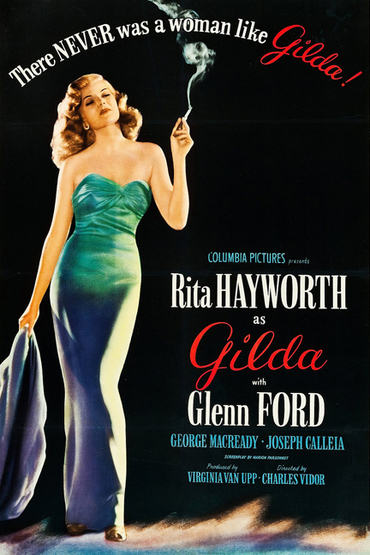

And slated for TCM's 8pm slot was... Gilda (1946).

I wasn't pleased.

Gilda has been "quoted" in pop culture every decade since its release, to the point where I couldn't remember whether or not I'd actually seen it before.

I did know it wasn't Laura or Public Enemy — or even Psycho, which (as I explained before) I find cozy. And I'd really been counting on cozy...

Plus it co-starred Glenn Ford. Has there ever been a Glenn Ford Fan Club? Can you imagine Judy Garland singing to his 8 x 10 glossy rather than Clark Gable's? I don't hate Glenn Ford. He's just... whatever.

But I watched Gilda anyway.

Gilda has been called the anti-Casablanca. Released only a few years apart, both films were directed by Hungarian immigrants from scripts that weren't finished when shooting began. Both take place mostly in casinos, in an exotic, dangerous locale (in Gilda's case, Buenos Aires.) Two men — a tough American, a suave European —love the same gorgeous woman. Everyone desperately wants to get hold of Some Very Important Papers. Also: Nazis.

But whereas Casablanca is, ultimately, an ode to self-sacrifice and courage, the message of Gilda is ... what?

I don't mean the storyline is confusing, and anyhow, that wouldn't necessarily be a strike against it. According to cinema lore, no one involved in the making of another classic 1946 film, The Big Sleep, could understand the plot, not even the guy who wrote it; the old movie buff joke that "The Big Sleep is about a really sexy bookstore" conveys the general consensus that nobody cares:

But with Gilda, the confusion comes in not with the plot, but with the characters. The two men keep talking about how much they love Gilda — except for all the times they talk about hating her. Gilda veers back and forth about Glenn Ford's Johnny in the same way, sometimes in the span of seconds. Their feelings flip on and off as if connected to a light switch, except that at least a light switch operates by universally acknowledged laws of science. Emotional cause and effect doesn't exist on Planet Gilda. Visitors — I mean viewers — often experience disorientation as a result.

The "Czar of Noir," film historian Eddie Muller, says acclimating to Planet Gilda requires accepting that "the subtext is the plot" — said subtext being, of course (I almost wrote "naturally"...) gay.

Now, before you groan, some evidence exists that Gilda's notorious gay subtext is authentic and not the product of "queer" post-modern academic fever dreams. I said "some": Glenn Ford told gay film historian Vito Russo, author of the invaluable The Celluloid Closet, that he and co-star George Macready "both knew they were playing homosexual characters." However, this was news to the director, Charles Vidor, who responded, "Really? I never had any idea those boys were supposed to be like that!"

In fact, gay characters were a commonplace trop in films noir, as a signal that we were now entering the genre's cynical, decadent underworld.

Of course, these characters' distinguishing characteristics were "coded;" Imagine how chuffed John Huston must have been when he got the word "gunsel" past the Hay's Office censors while making The Maltese Falcon.

Now, purists would call Gilda a film gris, but anyway:

Over the years, murmurs about "gay subtext" in Gilda centered on its contrived premise: Glenn Ford as Johnny, an American tramp picked up on the Buenos Aires waterfront by Ballon (George Macready), a mysterious industrialist/casino owner cruising the docks looking for a "friend" and carrying a suspiciously phallic cane with a protruding dagger. Johnny becomes Ballon's "boy" and eventually takes over his casino and then Gilda, Ballon's new wife. There's only sexual attraction between glowing Hayworth and brooding Ford [whose] Johnny is more corny juvenile delinquent than rough trade. So-called "gay subtext" is only a tease—it's meant to titillate viewers despite the film's shabby plot (involving Nazis, tungsten and international law). Gilda isn't really about sexual crosscurrents or bisexual allure.

So declares... gay film critic Armond White.

And I'm with him. If Vidor and co. were trying to get something past the censors, it's unclear what that "something" was, even from the production notes.

Honestly? Gilda's highly touted "clever" dialogue is undeservedly pleased with itself for the most part. The would-be double entendres are frequently more like "one-and-a-halfs," the verbal equivalent of those human unfortunates who are born with a misshapen vestigial twin.

And that dumb ending...

Does it matter? Gilda is a treat to look at, especially the recently restored version that, in keeping with its general policy, TCM airs by default. The black and white's uncommon platinum sheen is the perfect setting for Rita Hayworth at, arguably, her most ravishing.

But, at the risk of sounding, well, "corny" and "juvenile," I didn't care about these characters. You have to fast forward all the way to Chinatown (1974) to meet a comparable crew of charmless incorrigibles that you really wish you hadn't. And I never "got" Chinatown.

Those winter afternoon sunsets will soon return to annoy me again. I really need to finally buy my own damn copy of The Roaring Twenties or something so I'll be ready this year.