The sun'll come out

Tomorrow

Bet your bottom dollar

That Tomorrow

There'll be sun...

Last week we celebrated "Put on a Happy Face", the biggest song from the first Broadway hit of Charles Strouse, who turned ninety last Thursday. When it all comes together and you have a hit show and hit film and hit songs with a zillion recordings on the scale of Bye Bye Birdie, it's hard to believe that there will be tomorrows when the sun doesn't come out, when you bet your bottom dollar and lose it all. In the decade after Birdie, Strouse had shows that did okay, and shows that missed, and a few film scores, and a big hit with Lauren Bacall (Applause) that nobody really remembered the songs from, and one of the loveliest and most touching ballads to emerge from the Sixties ("Once Upon a Time"). But nothing that really landed the way Bye Bye Birdie had.

And then one day in early 1972 the telephone rang, and a chap called Martin Charnin was on the line: "Hey, I got a great idea for a show!"

"What is it?"

"I can't tell you over the phone. You have to come to the office."

Who's Martin Charnin? Well, he made his Broadway debut in 1957 playing Big Deal, one of the prancing Jets in West Side Story. And, in between saying "Gee, Officer Krupke, krup you!" eight times a week, he found himself intrigued by all the writing and directing and composing and producing and show-doctoring and the rest of it. In the decades since, he's become a jack of all trades, and master of more than you might expect. I think of him as a kind of a general man of the theatre ...and television, and movies, and records. Charnin's is a name that turns up in the credits of Barbra Streisand albums, and Jack Lemmon TV specials, and John Belushi stage revues. I interviewed him once for a BBC special on Richard Rodgers. And, if you're wondering what Martin Charnin has to do with the most successful of all Broadway composers, well, for twenty years there was Rodgers & Hart, and then for another twenty there was Rodgers & Hammerstein, and thereafter there were two shows by Rodgers & Charnin - both of which flopped: Two by Two, with Danny Kaye, and I Remember Mama, with Liv Ullmann. Nevertheless, that's two more shows than most young lyricists get to write with Dick Rodgers - and it remains a fact that, after Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein, Martin Charnin was Rodgers' third most frequent collaborator.

One December, he was in the old Doubleday's bookstore on Fifth Avenue, Christmas shopping. He chanced to see a lavish coffee-table book of old Little Orphan Annie comic strips. Harold Gray had created Annie, Sandy the dog and the beneficent Daddy Warbucks in 1924, and set them off - the poorest girl, the richest man, and the loyalest pooch - on a cascade of picaresque adventures that ran for almost a century, until the strip's cancellation by its Chicago Tribune syndicators in 2010. (Today Annie & Co make occasional guest appearances in the surviving Dick Tracy strip.) Charnin knew a friend who'd love the coffee-table anthology, so he picked it up, bought it, and then joined the line for complimentary gift-wrapping. "It was a long line," he told me. "Very long. So I decided to skip the gift-wrap and took it home - unwrapped."

Which is how he happened, that evening, to find himself reading the book. He stayed with it into the small hours, and the following morning asked his attorney to contact the Tribune and get the stage rights. He would direct it, and write the lyrics - and then he started thinking about who else he wanted on the show: For the music, he reckoned Charles Strouse would be right; for the book, he had in mind Thomas Meehan. By the time he died last year, Meehan was the only Broadway librettist to have written three musicals that ran over 2,000 performances - Hairspray, The Producers, and the subject of this column. He also wrote Elf - The Musical, and, with Sylvester Stallone, a musical version of Rocky. Mel Brooks loved Meehan, collaborating with him not only on The Producers but also on Spaceballs and To Be or Not to Be, and the Broadway version of Young Frankenstein. (Just to tie it all together, Brooks' original 1968 film of The Producers was based partly on his experiences of a flop Broadway musical he wrote with Charles Strouse in 1962, All-American, Strouse's follow-up to Birdie.)

On Tom Meehan's death last August, Mel Brooks hailed him as "a giant of the theatre". Which is true. But in 1972, when Martin Charnin called him up to pitch Little Orphan Annie, Thomas Meehan had never set foot in a theatre except as a paying customer. He was a New Yorker humorist, a "Talk of the Town" contributor, whom Charnin happened to enjoy reading. So he gave him the usual spiel:

"Hey, Tom, I got a great idea for a show!"

"What is it?"

"I can't tell you over the phone. You have to come to the office."

So Meehan came to the office. And Charnin showed him the Little Orphan Annie book. And Meehan said: "Yuck."

At least Charles Strouse didn't have to leave the apartment. When Charnin told him to come to the office, he said, "Nah. Just tell me."

"No. You have to come to the office."

"I'm not coming to the office. Tell me."

"Come to the office."

"Stop that, will you? C'mon, tell me."

"Okay." Charnin paused. "Little Orphan Annie."

As Strouse told me years later, "What a dull thud that landed with."

Just six years earlier, he'd done a comic-book musical - It's a Bird! It's a Plane! It's Superman! - and it had bombed. And Strouse was wary of getting a reputation for turning two-dimensional cartoon icons into three-dimensional flesh-and-blood duds.

The show's composer and librettist were at least merely antipathetic to the idea. The A-list producers Charnin took it to were openly hostile. As he said to me, "For three years all I heard was: 'But she's got no eyes.'"

That's how two-dimensional Little Orphan Annie is, even by the standards of cartoon characters:

She has no eyeballs.

In the next five years, Charnin would blow through seventy-five grand trying to persuade Broadway bigshots to see what he saw in the hoariest of hoary comic strips. Eventually, Charnin, Strouse and Meehan wound up opening the show a long way from the Great White Way, at an exquisite but tiny jewel of a theatre, the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut in the summer of 1976. It wasn't a great tryout, and the word leaked back to the Schadenfreude set in New York that the show was in trouble - big trouble. But among those who happened to catch it was Mike Nichols, the Oscar-winning director of The Graduate. Nichols was not a producer but decided he'd like to be, and that this would be his first play. So he came on board, which was one of those good news/bad news deals for Charnin: Nichols was a well-connected guy, with a prodigious knack for extracting dollars from backers and spending them wisely (the original Broadway production of Annie cost 800 grand and made over $16 million); on the other hand, because he was an accomplished director of Neil Simon and Edward Albee, showbiz gossips all assumed, by the time Annie opened in New York in the spring of 1977, that the show worked because Nichols the producer had secretly taken over the direction from Charnin. That's not true, and the former was at pains to insist that the staging was all the work of the latter.

Aside from the difficulty Charnin had interesting anybody else in the idea, Annie suffered from all the usual problems that attend a musical. The opening number is the most important choice a show makes - whether it's "Summertime" in Porgy and Bess, or the "Fugue for Tinhorns" for the trio of horse-gamblers in Guys and Dolls. Annie originally opened with a song and a scene that, in Charles Strouse's words, turned into "a six-minute medley of coughing": the audience couldn't have cared less. So they swapped it out, and tried to establish more precisely the time - look, here's FDR! - and the place - here's some bums on the street in the Depression! Then they opened with a big production number - "It's a Hard-Knock Life". "Nothing worked," said Strouse. "Nothing interested the audience." So one day he suggested, "Why don't we open with the ballad?"

Everyone thought it was nuts. But Charles persisted, and Martin Charnin eventually agreed. And so a big splashy musical opened in the dormitory of a drab municipal orphanage, and a little girl singing of the mom and dad who gave her away:

Maybe far away

Or maybe real nearby

He may be pouring her coffee

She may be straight'ning his tie

Maybe in a house

All hidden by a hill...

And shyly the other orphans join in:

MOLLY: She's sitting playing piano

TESSIE: He's sitting paying a bill...

It's a beautiful, plaintive melody, and nothing gets in its way. There's just a little girl and her friends imagining another life - and by the end the audience was engrossed, and ready for the story:

So maybe now it's time

And maybe when I wake

They'll be there calling me baby

Maybe.

Maybe. A difficult song to pull off, but a boffo tentative title, a fragile child-like tune, and affecting words. "The audience loved it," said Strouse. "The reception was incredible, and we never looked back."

The biggest song in Annie was, like "Put On a Happy Face" in Birdie, something that had been lying around in Charles Strouse's trunk. It was originally a number called "The Way We Live Now", music and lyric by Strouse, that he wrote for a short film in 1970. He dusted it off again for a musical based on Flowers for Algernon that eventually opened in Edmonton, Alberta en route to London. Strouse, as many composers are, was working on two shows simultaneously, and it seemed to him that this tune was more suited to Algernon than to Annie. But at some point he offered it to Charnin, who wrote:

The sun'll come out

Tomorrow

Bet your bottom dollar

That Tomorrow

There'll be sunJust thinkin' about

Tomorrow

Clears away the cobwebs

And the sorrow

Till there's none...

They didn't know what they had. In the old days, shows ground to a halt for set changes: The curtain came down, and someone sang a song in front of it, while behind it the stagehands got busy lugging on the new set. By the Seventies, it was all fluid, and sets slid on and off in full view of the audience. So Andrea McArdle (who'd taken over the main role from another little girl deemed to be too sweet and insufficient in street smarts for Annie) sang:

Tomorrow!

Tomorrow!

I love ya

Tomorrow!

You're only a day away...

And on the last line she and Sandy the dog walked behind a flat (a wooden panel of painted scenery) as the new scene came sliding on - and the audience clapped appreciatively. "We thought they were applauding the set," Charles Strouse told me.

Then they figured it out - and "Tomorrow" became the message of the show, and the glue that holds it together, and as a bonus bequeathed us one of the dottiest moments in the history of Broadway. In the Second Act reprise of the song, Daddy Warbucks has a meeting with President Roosevelt, and Annie asks to tag along. She starts to sing "The sun'll come out...", and is shushed by various of the cabinet secretaries - which is not unreasonable, and probably what most of us would do if we were trying to hold a cabinet meeting and some grade-schooler started warbling. But FDR feels differently and commands his team to sing along. And so it falls to some of the best-known names in mid-twentieth century politics - longtime Roosevelt advisor Louis Howe, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, and America's longest-serving Secretary of State Cordell Hull - to join little Annie in belting out:

When I'm stuck in a day

That's gray

And lonely

I just stick out my chin

And grin

And say

Oh...The sun'll come out

Tomorrow...

The song is brilliantly poised: At a certain level, the notion that tomorrow is eternally "a day away" is as fatuous a political philosophy as Chauncey Gardiner's simpleton observations about the changing seasons and spring regrowth in Peter Sellers' film Being There (a couple of years after Annie). Charnin's chin-up lyric trembles on the brink of parody but without ever quite falling in, and Andrea McArdle and almost all who've followed have delivered it with utmost sincerity.

Still, I'm not sure Harold Gray, creator of Annie and Daddy Warbucks, would have cared for it. Until his death in 1968, Gray was a Republican, and during the Depression the comic strip was dismissed by The New Republic as "Hooverism in the funnies". Warbucks was not a New Dealer, and in fact, of all the violent deaths Daddy was prone to in the FDR years, the most poignant was when he expired due to sheer despair at Roosevelt's election. The President himself died in office in April 1945, and shortly thereafter Gray felt it safe to resurrect Warbucks, who tells Annie he'd merely been in a coma and adds, "Somehow I feel that the climate here has changed since I went away."

In a Harold Gray musical, Daddy would be dancing on FDR's coffin, not dueting with Harold Ickes.

Then again, the politics was essential for Tom Meehan. "There was no period per se," said Meehan, noting that Annie's adventures had continued from the Twenties to the Seventies. It was my idea to place it in the Depression in New York. I think of Annie at some level as a political play, and in 1972 the Vietnam war was continuing..."

...Vietnam, Nixon, Watergate, yada yada...

"Annie was perfect for the moment," Charnin said to me in the early Nineties. "We were coming out of a very cynical era - Nixon, Vietnam, recession - and suddenly Jimmy Carter was elected and we had hope."

I said I was impressed he could say that last bit with a straight face.

But it doesn't matter. In The [Un]documented Mark Steyn (personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore), I recount a conversation with the late Mike Ockrent, director of the West End and Broadway smash Me and My Girl, a low musical comedy about a Cockney who inherits an earldom. And Mike said he saw it as an indictment of class, imperialism and British ancestor worship, and I guffawed and said that what people liked about it was the tap-dancing and jokes like "Aperitif?" "No, thanks. I've brought my own." And Mike responded that, whenever you're working on a musical that appears to be light and fluffy, it's crucial to have some big important thought that underpins the thing because "the people working on it have to get some satisfaction" and "we've all been to university".

That's how I feel about the notion of Annie as "a political play". If that's what it takes for Meehan, Charnin and Strouse to produce a crackerjack musical, so be it. But 99 per cent of the audience is there for the girl and the dog and the optimism; nobody goes for Henry Morgenthau Jr. Nevertheless, there are periods in the national story when there is a consensus on the prevailing mood, even if not on the political remedies for it. And I think Tom Meehan is on to something with this observation:

In Act Two, as far as I'm concerned, Annie becomes a metaphor figure, appearing in the White House, standing on the desk and singing 'Tomorrow'. She stops being real and becomes totally a metaphor for the spirit of how to survive and get out of bad times, how to endure, how to keep on keeping on. That's what it's about.

Indeed. But, as for the song itself, "I thought it was wrong for Annie," said Strouse. "It doesn't fit. Every other song in the score could have been written in that period - by Harry Warren or Irving Berlin."

I think that's true of, say, "You're Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile", although I'm not sure about "Maybe" or "Hard-Knock Life". But Strouse argued that "'Tomorrow" is pure Seventies, in its melodic rise and fall, those harmonies - it's a contemporary number." A pupil of Aaron Copland and Nadia Boulanger, Strouse (as we noted last week) has always had a curiosity about rock'n'roll, but mainly the late Fifties stuff he nodded to in Bye Bye Birdie. "Tomorrow" sounds twenty years later, and foreshadows his poppiest score, a couple of years on, for Dance a Little Closer. "Flop" isn't quite the word for a disaster of that scale: in 1981 Dance a Little Closer closed on its opening night, and is thus preserved in memory as Close a Little Faster. Yet I have always loved the groovy, rhythmic score, albeit disfigured by a very bad Alan Jay Lerner book.

But theatre is often a combination of happy accidents, and something about a 1930s cabinet singing a 1970s number clicked. "Tomorrow" was a forerunner of the on-the-nose, declarative, power ballads that would become a theatrical staple with Les Miz and a hundred lesser shows through the Eighties and Nineties. And its contemporary sensibility made it one of the last widely covered Broadway take-home tunes: Within a year, Barbra Streisand, Lou Rawls and the r'n'b group the Manhattans had all recorded it, and Grace Jones did well with a somewhat harsh and unpleasant disco arrangement. My personal favorite through the years has always been Elaine Paige's splendid uptempo version, which has all the energy of Grace Jones' but (as befits a great lady of the West End stage) also retains the pluck and spunk and optimism of Annie. If I ever chance to catch Miss Paige in concert, I'm always purring with contentment if "Tomorrow" is on the set list.

Still, you may feel differently. Jule Styne, composer of Gypsy and Funny Girl, dismissed Annie as "Oliver! in drag". Charnin, by contrast, considers it "the essence of Broadway... There's no helicopters [Miss Saigon], no chandeliers [Phantom], just pure emotional truth." The road from stage to screen has gotten far more tortuous in the last half-century (and in fact these days is more often traveled the other way round) but Annie has managed to be filmed thrice - by John Huston in 1982, by Disney in 1999, and by Jay-Z in an a black, hip-hop re-conception a couple of years ago. The writers haven't cared for any of them. Of the first Charles Strouse said to me, "Well, we'd all been working very hard on the show for years. And, when it's a success, do you want to go back to work on a film version? Or is it easier to take the two million dollars and go to the Virgin Islands?" As for the black version, well, Tom Meehan in many ways despised Harold Gray's source material ("fifty years of the endless, boring adventures of this dirty child") but, even in his contempt, identified the essence of Annie and enlarged it; Jay-Z, professing to admire and respect Strouse, Charnin and Meehan's Annie, nevertheless managed to kill its spirit.

No matter. The sun'll come out tomorrow for a new Annie, on stage or screen somewhere around the world. And "Tomorrow" has never gone away. It's in multiplexes right now, in Deadpool 2, as it was in Shrek 2:

Donkey: The sun'll come out Tomorrow/Bet your bottom...

Shrek: Bet my bottom?

It's powered innumerable TV commercials, and even some NFL end-of-season promo, with chastened and disappointed players exiting the changing room to:

Bet your bottom dollar

That Tomorrow

There'll be sun...

Very true. For a writer, it's always about tomorrow. It's fun to look back on opening nights in 1960 or 1977, but it's more exciting to look ahead to next month's opening, or next year's - to the next show, the next score, the next curtain... Happy birthday to Charles Strouse, a great American composer, still writing, still working, still chasing that next great idea for a new musical:

Tomorrow!

Tomorrow!

I love ya

Tomorrow!

You're only a day away...

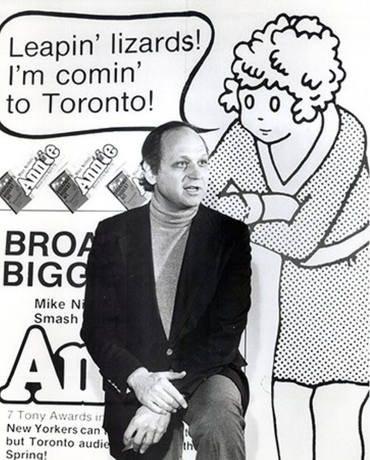

~Leapin' lizards! Like Annie in the poster at top right, Little Orphan Markie is also coming to Toronto: This coming Friday, June 15th, Steyn returns to his hometown to receive the very first George Jonas Freedom Award from Canada's Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms. You can find more details about the event here - and, if you enter STEYNCLUB18, you'll get 15 per cent off your ticket. We hope to see you there!

Charles Strouse is one of many legendary Broadway composers from Leonard Bernstein to Andrew Lloyd Webber Mark talks to in his acclaimed romp through a century of showbiz, Broadway Babies Say Goodnight. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

Happy birthday to The Mark Steyn Club, which is just beginning its second year. We thank all of our first-month Founding Members who've decided to re-up for another twelve months, and hope that fans of our musical endeavors here at SteynOnline will want to do the same in the days ahead. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that thanks to the Steyn Club this site now offers more free content than ever before in our fifteen-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club, and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits including an upcoming cruise. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.