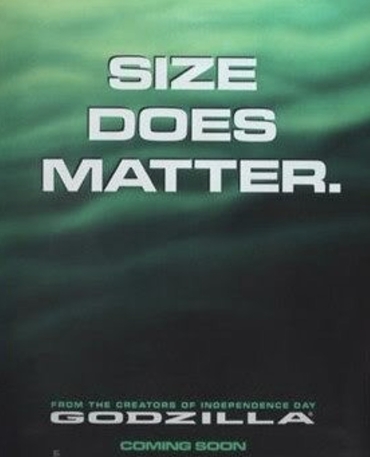

Twenty years ago this month, the Godzilla reboot du jour opened. Which isn't really an anniversary worth commemorating. Except that it also means it's the 21st anniversary of the ingenious advertising campaign launched a year earlier. Do you remember that one? They began showing the trailer in early summer 1997— the usual brilliant two minutes, featuring one of the film's better vignettes: some old coot fishing off the end of a rickety wharf suddenly gets a nibble on his line; as he struggles to hold on to his rod, the sea swells and the jetty begins to vibrate; Japan's most famous movie monster is about to arrive in Manhattan:

Size Does Matter.

Godzilla.

Coming in Summer 1998.

Audiences whooped and cheered and roared their approval. The studio, having spent $140 million making the film, blew through not much less on the campaign: absolutely everyone — according to delirious preview pieces from newspapers, magazines, radio and TV shows — was dying to see what the new Hollywood-size Godzilla looked like. But the producers were keeping him under wraps; there were stories about people close to the project trying to sneak out designs, and some fellows leaked models of the action-toy tie-in which proved to be false. Kodak (yes, that's how long ago it was) built their summer ad campaign around a guy trying to get souvenir snaps of the stompin' lizard.

And then the film opened.

And everyone who went on that opening weekend said actually, you know, it's kinda boring. By the second weekend, it was dead. Godzilla came ashore and fell flat on his face. It was the early days of the Internet, which was why Kodak and Main Street camera shops were still around, but Godzilla's formerly ingenious trailer inspired a prototype "meme", as altered (if not yet PhotoShopped) images from cyber-wags popped up observing "Plot Does Matter".

In the old low-budget days, when Godzilla was just a bit of eight inch Japanese Plasticine, the post-nuclear mutant sea monster was seen — by Tokyo audiences anyway — as a metaphor for the American occupation and submission of Japan. Forty-four years later, in the great Asiatic icon's first Hollywood film, from Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin (creators of Independence Day), metaphors of any kind seem to have been lost at sea. But, as Godzilla sets about trashing Wall Street, the Chrysler Building, Grand Central Station, the Plaza Hotel, Madison Square Garden, the Brooklyn Bridge and every other New York landmark, it's possible to see the old nuclear lizard as the embodiment of a gargantuan globalized culture that threatens to engulf the authentic American experience. Yes, I know it's a bit of a stretch, but the alternative is being bored to death — yawn, there goes the Flat Iron Building; didn't we see that the previous year in Independence Day?

In what passes for a humorous moment, the French secret service agents are equipped wuth sticks of chewing-gum to make them appear more American. But the film-makers themselves seem little better informed. There are aspects of Godzilla so bewildering as to make you doubt whether it was made by Americans at all: for example, no-one in the film, including the mayor, seems aware that New York City extends beyond the island of Manhattan. As for the French, we know they're French because they like ... croissants.

I recall having just read around that time some clever piece in The New Yorker by Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr (later the star honoree at Obama's first beer summit) asserting that what America calls "globalization" the rest of the world calls "Americanization". They may well do so, but I scoffed at the time that, at least as far as motion pictures are concerned, the "global" term is the correct one. American companies crank out most of this so-called global culture, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's very American. Rather than Americanizing Europe and Asia, this stuff was actually de-Americanizing American pop culture - and in particular making American movies less American.

There are many fine, professional aspects of Godzilla - not least the score by our old 007 pal David Arnold. But, given that 'Zil was the biggest dudsville loser lizard of the summer, you'd figure Hollywood would think twice about blowing any more 140-million-buck budgets on rampaging monsters, right? That was a lot of dough in 1998: You could have made a hundred Full Montys for the cost of this thing. But, even twenty years ago, that was no longer the way Hollywood ran the numbers anymore. Kevin Costner's $200 million Waterworld was a busted flush at the US box-office, but in the rest of the world they loved it. And Godzilla, after underwhelming at home, would prove equally lethal abroad. That's why, even as his size shrank, he mattered - and planning for next year's summer blockbusters proceeded unchanged. Americans were now the first victims of "Americanization", of Hollywood's dominant position as purveyors of entertainment to the planet. Size does matter: the movie business had gotten too big for the domestic market. In fact, if it's any consolation to the multicultural crowd, the most important or anyway the most reliable demographic among the cinemagoing public is young Asian men.

A decade and a half later, the talented producer Lynda Obst, with whom I once had a combative but very jolly time on a debate panel at Paramount, wrote a thesis on the subject that I discussed five years ago:

Lynda Obst has a new book out purporting to explain the age of globalized 'tentpole' 'franchise' movies selling on 'pre-awareness'. It's called, after her best-known romantic comedy, Sleepless in Hollywood...

What did I call those 3D glasses? Cardboard spectacles'? As Ms. Obst explains in her book, they love 3D overseas. So Hollywood now makes cardboard spectacles for the youth of developing countries, a half-billion-dollar summer stock for the barns of Asia. In Guangdong, the Chinese make America's Walmart filler; in Hollywood, America makes China's multiplex filler. The Chinese were the co-producers of the recent futuristic dystopian time-travel shoot-'em-up Looper, which I dimly recollect as a film so disciplined about its nothingness that, when the old Bruce Willis materializes from the future and meets his younger self and the young Bruce asks old Bruce if he'll remember meeting young Bruce upon his return to the future, old Bruce advises him not to get hung up on details. Don't even think about it.

And so it goes on: Iron Man 4, Cardboard Man 6, Franchise Man 12. I'm half-ashamed I even know that word, but that's Hollywood — from Franchot Tone to franchise drone.

Superheroes weren't yet dominant in the summer of 1998, but they were waiting, caped and spandexed, in the wings: 3DMan, TentpoleMan, RebootMan... Of all the pop-culture icons, only poor old Godzilla reliably fell at the first fence, every time. Four years ago, in the first half-decade of Warmzilla Michael Mann's Big Climate defamation suit against me, the 1998 Godzilla got rebooted for the even more moronized marketplace of 2014, and Y was thrilled to see this headline in (appropriately) The Daily Beast:

'Godzilla' Director Gareth Edwards Says Godzilla Is a 'God' Protecting Mankind Against Climate Change

Yeah, now you're talking! There's a metaphor I can get behind. Michael Mannzilla rampages across the planet squashing deniers all around and hurling SUVs into the volcano. But he doesn't stop there, and soon he's crushing decent hardworking scientists like Lennart Bengtsson and Judith Curry under his giant scaly reptilian foot. Jessica Alba, looking very fetching in a fake-fur-trimmed bikini, tries to tell Mannzilla he needs to get help, but he breathes blue flame at her and her bikini falls off...

Alas, Gareth Edwards decided to go in another direction:

At the beginning when they find the fossils, it was important to me that they didn't just find them—it was caused by our abuse of the planet. We deserved it, in a way. So there's this rainforest with a big scar in the landscape with this quarry, slave labor, and a Western company. You have to ask yourself, 'What does Godzilla represent?' The thing we kept coming up with is that he's a force of nature, and if nature had a mascot, it would be Godzilla. So what do the other creatures represent? They represent man's abuse of nature, and the idea is that Godzilla is coming to restore balance to something mankind has disrupted...

Oh, dear. So, like The Guardian's climate-change-kidnapped-the-Nigerian-schoolgirls story, it's just another it's-all-our-fault plaint:

Stories have been used for a long time to smuggle the morals of the day inside them, and today, people are worried about global warming.

Maybe at cocktail parties with studio vice-presidents. Fortunately, Gareth Edwards' powerful "message" was apparently all but undetectable to any but the most alert moviegoers. It might have been a more effective metaphor for that earlier Godzilla of 1998 - ie, the year global warming stopped, or "paused".

At my local movie theater that week, I had a choice betwen Godzilla in 3D and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 in 3D. That's it. And it's only gotten worse since. God, I'm beginning to pine for a chick flick, even in 3D: They're talking about their feelings right in your face! How about The King's Speech 2? He's b-b-b-b-back and this time he's a-a-a-angry! In 3D! It's like he's stammering right in your ear...

I'm thinking of pitching Paramount my new summer blockbuster Metaphorzilla, in which a giant monster starts terrorizing everybody and we all assume that it's a metaphor for something - climate change, Trump, Stormy Daniels' non-disclosure agreement - and then the horrible truth dawns that it isn't a metaphor for anything at all: it's just a two-dimensional cardboard character you can only see through 3D cardboard glasses...

~Tomorrow is the first anniversary of The Mark Steyn Club. If you're one of our first-day Founding Members, we thank you for your support these last twelve months, and hope you'll want to join us for the next twelve. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time; it's also an Audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have many other benefits. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we do have a special Gift Membership that makes a great birthday present. More details here.