One hundred years ago today - March 25th 1918 - a five-man band went into the Victor Studios in New York, and emerged with three minutes of manic abandon on an insistent theme:

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

I always associate those three words with the great pioneer discographer Brian Rust. For years, he hosted a Sunday evening show on Capital Radio in London called "Mardi Gras" dedicated to the early years of popular music "and all that jazz" (as he put it), and his theme music was always the Original Dixieland Jazz Band's famous recording of "Tiger Rag". Like most pop stations, Capital is very heavily formatted these days, but it was an eclectic joint way back when, especially on Sunday nights: Robin Ray's classical show, then "Mardi Gras", and to round out the evening an unpredictable talk show hosted by Mick Jagger's ex-, Marsha Hunt. I vaguely recall that Brian Rust got the gig because Richard Attenborough, Capital's chairman, liked a lot of the same kind of music. I didn't know much about it back then, and Rust introduced me to a lot of early jazz artists I've come to love.

In the Forties, he took a job at the BBC at what was then called the Gramophone Library, and realized that nobody really had a clue as to what gramophone records were out there. So he started researching and, funded by subscription, self-published two works that set the standard for all that followed, Jazz Records 1897-1931 and Jazz Records 1932-1942. (The latest edition is available as Jazz And Ragtime Records 1897-1942.) Along the way, he more or less invented a new form - "discography" - and today any producer at almost every record label embarking on a release of archive material will start his research with what they know in the trade as "JR" or "Rust". He had a fanatic's knowledge of the field. Many years ago, his home was burgled, and some of his treasured 78s were stolen. At the ensuing court case, the snooty barrister for the defense demanded to know how Rust could possibly be certain that this particular copy of King Oliver's "Sweet Baby Doll" was his. Because, he replied, there was "an audible click in the 17th bar of the third chorus". A record player was found, the court listened through, and the n'er-do-well went to jail for four months.

So this week's Song of the Week is dedicated to the memory of a man to whom this weekly feature and many like it owe a great debt. "Tiger Rag" was not an accidental pick as Rust's theme tune. It's popularly regarded as "the first jazz record", from a time when the word was so new it was spelt "jass". The very title of Volume One of Rust's own discography - Jazz Records 1897-1931 - would seem to refute "Tiger Rag"'s claim to be "the first jazz record". But in America the fruit of today's centenarian recording session was a nationwide sensation and it certainly did more than any other song or record before it to plant the word "jazz" in the national vocabulary.

Just to be boringly pedantic about it, though, "Tiger Rag" wasn't even "the first jazz record" by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. That credit would go to "Livery Stable Blues" and the "Dixie Jass Band One Step", released by the Victor Talking Machine Company on February 26th 1917. Nor was the "Tiger Rag" we know today even the first "Tiger Rag" recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. That honor goes to the "Tiger Rag" they cut for Aeolian-Vocalion Records in August of 1917, back when they were still spelt as the Original Dixieland Jass Band. But it was released as a single-sided vertical cut disc, which was like the Betamax of its day: You couldn't play it on most phonographs. So it didn't sell. Meanwhile, the Original Dixieland Jass Band changed their name to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and a few months later went back into the studio, this time at Victor Records, and on March 25th 1918 recorded the "Tiger Rag" that swept the nation. Brian Rust was so appreciative of the label's efforts on behalf of his nascent music form that he named his son Victor. You don't have to go that far to recognize the special significance of the second "Tiger Rag": It's wild, it's hot, it serves as a kind of reveille for the Jazz Age and the sheer abandon of American music in the Twenties.

Finding themselves with a smash hit, the ODJB started billing themselves as "The Creators of Jazz", which wasn't true, but you can't blame 'em for trying. In the years since, the standard critique has been that they were opportunist honkies who stole the black man's music and called it their own. All five men had previously played in a racially integrated band, and their leader, Nick La Rocca, didn't do his reputation any favors when, late in life, he insisted that no Negroes were involved in the creation of jazz, he was the form's sole inventor and "the most lied-about person in human history since Jesus Christ". I'm disinclined to judge an aural art form by the visual skin tone of its players, and, in these interminable disputes, envy Ray Charles, whom I quote in Mark Steyn's Passing Parade as saying that, as a blind kid listening to the radio in Florida, all he could hear was the music: "Take Artie Shaw," he said. "I didn't even know he was white."

But, setting aside Nick La Rocca's industrial-strength self-aggrandizement and taking his critics at face value for the sake of argument, even if you copy something you heard from some fellow in a Negro club, you've still got to be able to do it - and the ODJB can certainly play the stuff. Their best records still sound good after 90 years, which I doubt you'll be able to say about Justin Bieber. And, for a group overly fond of novelty songs, their repertoire has a weird topicality, at least in tunes like "Soudan" and "Lena From Palesteena". They'd gotten together in New Orleans, where all of them were at one time or another playing in Papa Jack Laine's Reliance Brass Band. In 1916, they joined the great exodus of black and Creole musicians up the mighty Mississipp' and headed for Chicago. They took with them the tune we now know as "Tiger Rag".

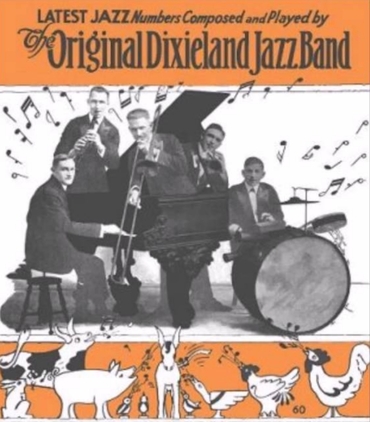

Where did it come from? Officially, it was written by the ODJB's members - Nick La Rocca, Eddie Edwards, Henry Ragas, Tony Sbarbaro, and Larry Shields - in the same way that in the rock era Top Ten songs are often credited to the entire band. But, as the old saying goes, where there's a hit, there's a writ - or at least a competing narrative. As far as I can tell, pretty much everyone who could carry a tune in New Orleans in the first decade-and-a-half of the 20th century insists he had a hand in the creation of "Tiger Rag". Jelly Roll Morton, who claimed to have invented jazz in 1902, told the folk musicologist Alan Lomax that he'd based "Tiger Rag" on a French quadrille he happened to have heard. This would make a quintessential slice of 20th century Americana a bit of Europeana from the 19th century or earlier. But, as far as I know, neither Jelly Roll nor anyone else ever actually identified the composer of the precise quadrille that got his juices going.

Who else claimed a hand in "Tiger Rag"? According to some, Papa Mutt Carey, brother of the bandleader Jack Carey, got the first section from a folio of quadrilles and gave it to the Carey band to work out the rest: The second and third sections were mostly the work of the clarinettist, George Boyd, and the "Hold that tiger!" finale was cooked up by Jack Carey and his cornet player Punch Miller. It was supposedly Carey who created the distinctive tiger "growl" effect for his trombone. The result was known around New Orleans under two names: Black musicians called the tune "Jack Carey"; white musicians called it "Nigger Number Two". With the former, you can shout "Play Jack Carey!" in lieu of "Hold that tiger!"; with the latter, it's probably best not to speculate. An early record by Johnny De Droit, "Number Two Blues", is very similar, as is "Weary Weasel" recorded by Ray Lopez, Abe Lyman and others.

But the ODJB made their claim stick, and made the tune stick. You can look at it as a conventional two-step very intensely syncopated, but La Rocca on cornet, Eddie Edwards on trombone and especially Larry Shields on clarinet played the hell out of the thing. The result electrified white audiences in northern cities as no other jass record quite had, and this band more than any other planted the jazz bug in the brains of listening youngsters, including Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman and (as he reluctantly conceded to me) Artie Shaw.

Along the way, "Tiger Rag" acquired a lyric, by Harry Da Costa or Harry De Costa. Any way you spell it, he was an active Tin Pan Alleyman at the time, the co-author of "The Eyes Of Heaven (My Mother's Star)", "Hitch Up The Horse And Buggy", "Guide Me On, River Amazon", "The Little Grey Mother Who Waits All Alone", "Are You Half The Man Your Mother Thought You'd Be?", "The Dumber They Come, The Better I Like Them" (written with Eddie Cantor and Fred Ahlert, whose grandson Arnold Ahlert has been an occasional correspondent to our mailbox), and, of course, "Tiss Me Or Ya Dotta Det Out". I wouldn't want to pay the mortgage with the royalties from that catalogue, although "Hello, Central, Give Me France (We Want Our Daddy Dear Back Home)" did okay at the tail end of the Great War. Still, for "Tiger Rag", he didn't overly complicate things, punctuating the little tiger "growls" with three-word responses :

Where's that tiger?

Where's that tiger?

Here's that tiger!

Where's that tiger?

Here's that tiger!

Where's that tiger?

Here's that tiger...

As longtime readers know, with "Lullaby of Birdland" and other examples over the years, we've discussed the problematic matter of turning instrumentals into "songs":

The trouble with putting words to an existing jazz instrumental is that it tends to come out sounding less like a song than as an instrumental somebody's singing a lyric to. It lacks the unity of a conceived song.

In the case of "Tiger Rag", Harry De Costa did a better job than one might expect from the writer of "You Can't Gyp A Gypsy". Instead of trying to turn it into a conventional song, he provides just enough words to occupy any vocalist who fancies taking a whack at it, and the words he provides have the measure of the tune. That's to say, they're in its nutty, high-energy, hyper-intense spirit. An instrumental is abstract. Words make it specific and vivid, and so you want them to be the right ones: "Hold that tiger!" declares that tune. Non-jazz fans loved it, and immediately arrangements were cranked out for small-town marching bands and genteel Palm Court trios. In the Jazz Age, who didn't hold that tiger for at least a couple of minutes? Sophie Tucker did, and Ethel Waters, and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. In 1930, Satchmo recorded it. As HRH The Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII, later still the Duke of Windsor) enthused:

I'd rather hear Louis Armstrong play 'Tiger Rag' than wander into Westminster Abbey and find the lost chord.

Years later, in 1960, at a stop in colonial Kenya, Armstrong was asked what he thought of His Highness' remark. He replied:

I agree with that.

By the time of Armstrong's record, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band had long since broken up. The public tired of them very quickly after "Tiger Rag". Nick La Rocca, the leader, was irritating in an oddly contemporary way. He gave interviews full of what we'd now call soundbites ("Jazz is the assassination of the melody"), and he devoted as much time to promotion as to music (top hats that spelled out "D-I-X-I-E"). But sliding popularity brought on a nervous breakdown, and the band went their separate ways. The rest of the guys, whom La Rocca disparaged as irrelevant and worthless, re-united a decade later, and recorded an even more frantic "Tiger", but by then even their own song had slipped away from them. In 1931, a brand new version from a brand new group had made it to Number One on the charts. It was the Mills Brothers' first hit, and the song that made them stars, in a rip-roaring arrangement that's a crazy blend of scat and yodeling. All the big bandleaders of the Thirties did it - Ray Noble, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, and, clocking in at five-and-a-half minutes, Duke Ellington. The star instrumentalists got to it, too - Art Tatum, Django Reinhardt, Larry Adler. In Britain, Ambrose recorded it with a vocal group singing in Scots, Welsh, Mancunian, French and Yiddish dialect.

But, as the Swing Era got swingier, "Tiger Rag", the alarm clock that started the era of mass-appeal jazz, came to be regarded as an anachronistic novelty. Its greatest success, a multi-tracked blockbuster hit (with extended lyrical variations - "Here, kitty, kitty, kitty... Here, puss, puss, puss") for Les Paul & Mary Ford in 1952, was also a kind of last hurrah. To be sure, Liberace slurped his way through it, and Andre Kostelanetz, and Chet Atkins countryfied it, and Bob Wills played it as western swing, Spike Jones played it for laughs, and Charlie Parker took it seriously, in a version that hints at bebop, and which Brian Rust, no fan of what Bird did to jazz, would probably not have cared for. But by now "Tiger Rag" was an archivist's curiosity rather than a living part of the repertoire. In more recent years, Joe Jackson has recorded it, and Jeff Beck resurrected it for a tribute to Les Paul in a truly lead-weighted, clubfooted reading that makes you realize that, for all the criticism of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band as "white imitators", your average pop instrumentalist today isn't even capable of playing the thing with any brio.

On the other hand, Clemson University claimed it as their fight song ("the song that shakes the southland") in 1942, and have never given up on it. Every other school with a team called the Tigers is keeping it in business, too, including the Louisiana State University Tiger Marching Band, and the Cuyahoga Falls Marching Tiger Band. Nick La Rocca would probably have not been surprised by the Tiger Marching Bands and the Marching Tiger Bands, but the version for the carillon on the Clemson campus might have impressed him. And, while it languishes among jazz players, there are worse forms of posterity than a stadium full of sports fans at a hometown game bellowing out:

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

Hold that tiger!

My only fear is that it's such a single-minded roar of attitudinal assertiveness that it's only a matter of time before the sensitivity pansies of American educators get it banned as a triggering micro-aggression. Say, there's a lyric: "Hold that trigger! Hold that trigger! Hold that..."

Hold that tiger while you can.

~Many of Steyn's most popular Song of the Week essays are collected together in the aforementioned book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the special promo code at checkout to enjoy the special Steyn Club member discount. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club, and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.