We have a choice of musical diversions for you this weekend: please check out the pre-Valentine edition of The Mark Steyn Weekend Show, which among other delights features Mark's compatriot, the great singer-pianist Carol Welsman, offering a brace of truly classic love songs. On the other hand, if your idea of an iconic love song is one not about a mere sweetheart but about childhood and Dixie and mammy's arms and the Swanee river, then you're in luck...

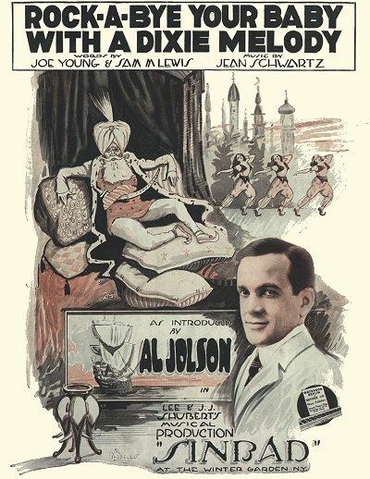

One hundred Valentine Days ago, on February 14th 1918, a new Shubert Brothers production opened at the Winter Garden in New York. It was set in Baghdad, and indeed was one of the most successful musicals ever set in Iraq until Saddam Hussein's musical (seriously - adapted from his novel Zabibah and the King), which was the non-surprise hit of the 2001 Baghdad theatre season. A century ago on Broadway, Sinbad didn't have quite the advantages Saddam did - the ability to torture hostile critics to death, etc. So February 14th was an evening of the usual first-night tensions. The story, by Harold Atteridge, opened at a Long Island country club, where the heiress Nan van Decker is being wooed by rival suitors and consults a crystal ball on the matter. The next thing you know, we're transported to old Baghdad to meet various characters from the Arabian Nights. This plot has a certain logic, at least in musical comedy terms. Except that amidst the machinations is a colored porter played by a white man in blackface. The New York Times drama critic loved it:

[The porter] informed the audience that he had been looking for barbed wire so he could knit the Kaiser a sweater, and the show really was started.

Because how else would you start a show about Sinbad the sailor in old Baghdad? Kaiser gags don't really make a lot of sense, especially in a show about Mesopotamia, which was part of the Ottoman Empire, which was on the same side as the Kaiser in the Great War. But hey, you don't want to overthink these things. The Shubert brothers had installed a ramp at the Winter Garden, which extended from the stage deep into the audience. That didn't have much to do with the plot, either: The sets were lavish and exotic - "the Island of Eternal Youth", "the Cabin of the Good Ship Whale", "the Grotto of the Valley of Diamonds" - but the ramp was bare. And, having landed with his killer sweater-knitting gag, the porter in blackface and white gloves bounded down the ramp, got down on one knee, and sang an introductory verse:

Mammy mine

Your little rolling stone that rolled away

Strolled away

Mammy mine

Your rolling stone is rolling home today

There to stay!

I want to see your smiling face

Smile a welcome sign

I want to feel your fond embrace

Listen, Mammy mine!

Pace the Times man, the show wasn't really started, not yet, not quite. That happened when the porter wrapped up the intro, clasped his white-gloved hands together, and swung into the chorus:

Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody

When you croon

Croon a tune

From the heart of Dixie...

Somewhere behind him a plot about Baghdad and the Arabian Nights and an heiress with a choice of suitors was waiting to resume, but out in the orchestra seats nobody missed it. The man crooning the tune was Al Jolson, and the song, according to America's newspaper of record, was "Rock-a-Bye You [sic] Baby with a Dixie Melody". Close enough for Times work. For all his star power, Jolson suffered from terrible first-night nerves and at the Winter Garden large buckets were placed in both wings in case he needed to bolt for the side and throw up. He needn't have worried, not as the Times saw it:

The Winter Garden likes Jolson and Jolson seems to like the Winter Garden--so a joyful time was had by all.

Up to a point. When Jolson was off-stage and headed for his dressing room, the first responsibility of his dresser, Frank Holmes, was to turn on the faucets lest Joley should hear his fellow cast members receiving applause and be discombobulated by the realization that someone other than him was contributing to the show's success. To be sure, out there on the aisle, you could occasionally find a rare theatregoer anxious to see the story they were supposed to be seeing. Frank J Price in The New York Telegram, for one, was unimpressed by all the blackface eye-rolling:

Al Jolson was starred - just why it is hard to say. It is a great pity to spoil a series of spectacles as picturesque and beautiful as art and a lavish expenditure of money can make them with a setting so bizarre and out of place, so incongruous and repellent as negro comedy that it would have been considered cheap and inadequate in a Bowery variety theatre of thirty years ago.

The only review you'd enjoy reading a century on is Dorothy Parker's for Vanity Fair, which contains a couple of not-quite-top-drawer-but-amusing-enough Parkerisms such as:

Sinbad is produced in accordance with the fine old Shubert precept that nothing succeeds like undress.

Mrs Parker was much exercised by the under-garbed chorines:

Of course, I take a certain civic pride in the fact that there is probably more nudity in our own Winter Garden than there is in any other place in the world, nevertheless, there are times during an evening's entertainment when I pine for 11.15, so that I can go out in the street and see a lot of women with clothes on.

It's clever and droll and better written than the Times and Telegram reviews. But it entirely misses the point - which is the electric connection between star and audience when that porter steps out of the plot and socks a new song (one that Mrs P apparently didn't even notice) way out to the back of the balcony:

Just hang that cradle, Mammy mine

On the Mason-Dixon Line

And swing it from Virginia

To Tennessee with all the soul that's in ya...

"Rock-a-Bye Your Baby" has had a pretty good run in the ensuing century: Joley sang it until the end. And not long after his death in 1950 Judy Garland took it up at the behest of Sammy Cahn, who said to me that he'd told her she was the greatest entertainer since Al Jolson and therefore should sing a Jolson song just to underline the point. In 1956, Judy came down with strep throat, and her husband, Sid Luft, chasing frantically for someone to fill in, eventually called Jerry Lewis. Jerry was having a bad time of it since being dumped by Dean Martin, and he hadn't sung on stage since he was five years old. Nevertheless, that night, after the usual jokes and clowning, he sang a song he'd loved since childhood, "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby":

When I was done, the place exploded. I walked off the stage knowing I could make it on my own.

He put it on a single, which made the hit parade. And then Capitol made it the centerpiece of an album, Jerry Lewis Just Sings, which hit Number Three on the charts and sold a million-and-a-half copies. And until the end of his life Sammy Davis Jr, whenever he chanced to share a stage or the "Jerry's Kids" Telethon set with Lewis, insisted that Jerry drop the child-man clowning and sing "Rock-a-Bye". In the Eighties, I heard Aretha Franklin sing it live in concert - in the midst of "Respect", "Natural Woman", "Until You Come Back to Me" and all her other hits - and it sounded great, because she loved it. Latterly, Rufus Wainwright (son of Loudon) has done it as part of his recreation of Judy Garland's live act.

So a good run for a hundred years. As for the next hundred years, I fear, as part of the war on Confederate iconography, that that dear old mammy mine may get caught in the crossfire. In 1918 there were literally thousands of blackface performers, but Jolson was the greatest of them all, whose raw emotional power it took a mask of burnt cork to liberate. In Broadway Babies Say Goodnight (personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the Steyn store), I write:

For many Jews, blackface was a code, one race's pain speaking in the form of another. There were double acts like 'The Hebrew and the Coon': the Hebrew was the genuine article; the coon was Al Jolson. Uniquely excluded from the Ellis Island myths, America's blacks do not, understandably, subscribe to the view that cultural appropriation is the sincerest form of flattery.

But masks have their uses. A couple of years after "Rock-a-Bye", Jolson sang the definitive mammy song, "My Mammy", and for the next three decades always lapsed, in the second chorus, into the following semi-spoken extrapolation:

Mammy-- Mammy, I'm comin'!

Oh God, I hope I'm not late!

Look at me, Mammy! Don't you know me? I'm your little baby!

This evolution from the published text has its origins, supposedly, in the death of Jolson's own mother. He did, indeed, arrive too late in the onset of her final illness, and she no longer recognized him.

Would he have offered up something so visceral and personal without the cover of blackface? Doubtful. By comparison with mammy songs, mother songs were far more stiff and genteel. As part of the general historical illiteracy of our age, we tend to confuse mammy songs with the "coon songs" of a generation earlier - leaden verse-and-chorus numbers dependent on comic lyrics we no longer find funny: "All Coons Look Alike to Me", "Coon! Coon! Coon!", "If the Man in the Moon were a Coon", etc. But the mammy songs of the teens and twenties were jazzier and achier and heartstrings-wise tuggier, with a genuine musical purchase on black and white audiences alike. Which is why, whatever one makes of their original socio-cultural context, they effortlessly outlasted it.

Of course, to return to that point about "cultural appropriation", it's true that, when you set out to croon a tune from the heart of Dixie, no southern blacks need be involved in the creation thereof. But then no southern whites need be, either. Almost all the landmarks of the genre were written by New York Tin Pan Alleymen who'd never been south of Canal Street. Almost all of them (including this one) were by Jews, but then, in the golden age of American song, what wasn't? With respect more specifically to "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody", the critical element seems to be Hungarian.

The first Hungarian on the scene was Sigmund Romberg, born in Nagykanizsa in 1887. Like most Hungarian composers of his generation, he wanted to write operettas about merry widows and gay hussars, and countesses masquerading as serving wenches romancing princes masquerading as stable lads. But he was living in New York and under contract to the Shubert brothers, who wanted him to write musical comedy numbers for those underdressed dancing girls Dorothy Parker was complaining about. So he did his best, but he was hopeless at it. He and Harold Atteridge were hired to write the score for Sinbad, and, if you can sing a word of "Where Do They Get Those Guys?" or "On Cupid's Green", you belong to the world's most statistically undetectable demographic. In the Twenties, Romberg would finally achieve his ambition and get to write theatre scores of the Franz Lehár school for what remain his most enduring works - The Student Prince, The Desert Song and The New Moon. As for Atteridge, he wrote thousands of lyrics neither better nor worse than those of Sinbad, and only once did lightning strike, for the still sung "By the Beautiful Sea".

What do you do when you've got a dud Broadway score by a Hungarian still pining for the goulash? Why, you bring in another Hungarian! Jean Schwartz was born in Budapest in 1878, sailed for New York at the age of thirteen, and eight years later was sufficiently Americanized that he published a cakewalk. In 1910 he had a monster hit with "Chinatown, My Chinatown", and at the time of Sinbad he was having a pretty good war thanks to songs like "Hello Central! Give Me No Man's Land". Schwartz wrote the two biggest numbers on that Valentine's opening night at the Winter Garden in 1918: not only "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody", but "Why Do They All Take the Night Boat to Albany?" - which is the first title that springs to mind when a chap's asked to add a couple of tunes to an Arabian Nights musical. "Rock-a-Bye" is an extremely cunning piece of composition, starting with that leap upward on "Ba-by" and its even more heart-wrenching recapitulation in:

Weep no more, my la-dy!

Sing that song again for me...

And the seesaw phrasing of these four bars almost seems to invite that stirring martial percussive trumpetty-trump with which it's been accompanied for most of its existence:

A million baby kisses I'll deliver

The minute that you sing the 'Swanee River'...

The lyrics to "Rock-a-Bye" are by Schwartz's then regular writing partners, Sam M Lewis and Joe Young. Young isn't in the least bit Hungarian, but Lewis, although born in New York, does have a Magyar connection. Aside from "Dinah", "How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?", "Just Friends", "In a Little Spanish Town", "Street of Dreams" and "For All We Know", Lewis also wrote the English lyrics to "Gloomy Sunday", the so-called "Famous Hungarian Suicide Song", as it was parenthetically billed on the label of Billie Holiday's record thereof. Its composer, Rezső Seress, was born in Budapest in 1889, and, unlike Sigmund Romberg and Jean Schwartz, he didn't get out. So by 1932 he was very depressed at the way Hungary and Europe were going, and wrote a piece called "Vége a világnak", which means "The world is ending". The Hungarian poet László Jávor wrote a slightly subtler lyric that translates as "Sad Sunday", in which the singer wishes to commit suicide after the death of a lover. "Sad Sunday" got sadder in translation - "Sombre Dimanche" in French, and then "Gloomy Sunday" in Sam M Lewis' English text. You can't complain he doesn't live up to the title:

Gloomy is Sunday

With shadows I spend it all

My heart and I

Have decided to end it all...Death is no dream

For in death I'm caressing you

With the last breath of my soul

I'll be blessing you...

By the end of the Thirties, the song was said to have been responsible for nineteen suicides, although it's hard to verify as at that time Hungarians were remarkably suicidal. Nonetheless, the BBC decided to ban Billie Holiday's recording as detrimental to wartime morale. However many listeners decided to kill themselves, we know that at least one singer of the song did (Billy Mackenzie of the Associates, in his dad's garden shed in Auchterhouse in 1997), and so did the composer. Rezső Seress hurled himself from the window of his flat in January 1968, but survived and was taken to hospital in Budapest, where a few days later he garotted himself with a wire he found in his room. The success of "Gloomy Sunday" was said to have made him even gloomier, as he realized he'd never write a second hit. If you're interested, his other songs include "Fizetek főúr" (The drinks are on me) and "Én úgy szeretek részeg lenni" (I enjoy being drunk).

So Sam M Lewis wrote with the most lugubrious of Hungarian composers, and with the peppiest and jazziest. One cannot confidently declare "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Magyar Melody" as a general operating principle: one is obliged to discriminate between Jean Schwartz, on the one hand, and, on the other, Romberg (in his pre-Student Prince period) and Seress (in any period). Still, it's very strange to ponder the Hungarian currents coursing through this most American of songs:

Just hang that cradle, Mammy mine

On that Habsburg-Ottoman line

And swing it from Slovenia

To Timișoara with all the love that's een ya...

It's worth noting just how good Lewis & Young's lyric is - not just the notion of the Mason-Dixon line as something to swing a baby's cradle from, or the early use (in an American pop song) of "croon", and the effusive generosity of a "million baby kisses", but the more general way it takes all the familiar Dixie imagery and refreshes it, very memorably. Yet, oddly enough, the latter half of the text is mostly about other songs:

'Weep no more, my lady'

Sing that song again for me

And 'Old Black Joe'

Just as though

You had me on your knee

A million baby kisses I'll deliver

The minute that you sing 'The Swanee River'...

All three of those song quotations are from Stephen Foster: "Swanee River" is more formally known as "Old Folks at Home" (1851, and latterly the state song of Florida); "Weep no more, my lady" is a line from "My Old Kentucky Home" (1842), "Old Black Joe" (1853), is the song of a black servant nearing death. And all of the above would have been known to everyone listening to "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby" for the first time in 1918, and for many decades afterwards. (In fact, "Old Black Joe" was one of the last recordings of Al Jolson's life, made just three months before his death.) As Stephen Foster has slipped from universal recognition, the allusions are not quite so obvious: singers began to substitute "sing soft and low" for "Old Black Joe", and "Weep no more, my lady" came to be heard as not a song request but as the tears of a mammy overcome by the return of her wandering one.

In the end, it all comes back to Jolson, the self-styled "World's Greatest Entertainer". Early on, he made small lyrical amendments: "If you will only sing that 'Swanee River'", etc. He opted, from the get-go, to swing it from Virginia to Tennessee not "with all the love that's in ya" but with all the soul. It's an unusual word to find in this context in 1918, but by the time I heard Aretha sing it in the Eighties, when "soul music" was the formal designation for black pop, it kind of authenticated the song, conjuring the vision of a mammy singing so soulfully she becomes herself a veritable Aretha. I don't know what possessed Joley to so amend the text, but I'll bet in return he asked for a piece of the writing royalties. His view was that he was the difference between a song and a hit - that he could take anything and sell it. "I could pick up a telephone book and make the folks cry if I wanted to," he said. So for the reprise he would amend a line here, add a word there, and insist on "cutting in" on a percentage of the song. To music publishers around town, he was known mordantly as "the best second-chorus writer in the business". In the program for Sinbad, Jolson was credited as the co-author of six numbers. They include "The Bedalumbo" (a dance craze that no one ever danced to), "Raz-Ma-Taz" and "The Rag Lad of Baghdad" - which is to say they're as forgotten as the Sigmund Romberg story songs. Schwartz, Lewis and Young resisted the graspings of Jolson, and their songs - "Rock-a-Bye" and "Night Train to Albany" - were the smashes of the night.

Jolson played in Sinbad for over a year on Broadway, and then toured it around the country for another two. The story by Harold Atteridge and the Sigmund Romberg tunes and the underdressed chorines and lavish sets stayed the same, but Joley in blackface and white gloves, down on one knee at the end of the runway, continually refreshed the act, adding new songs that took his fancy - "Swanee" in 1919, and then "My Mammy" and "Avalon". On that last, Al finally succeeded in cutting himself in on a blockbuster ...only to get sued by Puccini's publishers for lifting the opening phrase from "E lucevan le stelle" in Tosca and winding up losing all his royalties to some litigious operatic Italian. What did he care? The next morning there'd be songwriters at the door pitching him next month's "Mammy" or "Swanee" - and however indifferent it was, it had to be better than the score or the story or the character he was meant to be playing. As he asked the audience one night in the Second Act:

Do you want the rest of this plot? Or would you rather hear me sing a few songs?

So he sent the rest of the cast home, and then turned to the conductor: "Professor, if you please..." He stayed down the far end of that Shubert runway, an arm's length from his fans, until one in the morning - and still they wanted more:

Awww, they're playin' 'Weep no more, my lady'!

Mammy, sing it again for me

And 'Old Black Joe'

Just as though

You had me on your kneeA million baby kisses I'll deliver

If you will ...oh, please sing 'The Swanee River'

Rock-a-bye your rock-a-bye baby

With a Dixie melody!

And then it was over, and the world's greatest entertainer went back to an empty dressing room. As Eddie Cantor put it:

When the curtain came down, Jolson died.

~Many of Steyn's most popular Song of the Week essays are collected together in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the special promo code at checkout to enjoy the special Steyn Club member discount.

Also for Mark Steyn Club members: If you disagree with any or all of the above, feel free to rock-a-bye your baby with a splenetic denunciation across our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content - in fact, we're providing more free content at SteynOnline than ever before - but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so do have your say. For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.