The Vietnam War cast, as they say, long shadows. It left, as they also say, deep scars in the American psyche. And among those shadows and scars is the fact that every so often I find that, unbidden, a line of lyric pops up into my head - such as:

And the wants and the needs of a woman your age, Ruby, I realize...

Also:

And if I could move I'd get my gun and put her in the ground...

The Sixties gave us the occasional pro-Vietnam hit ("Ballad of the Green Berets") and anti-Vietnam hit ("I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die Rag"), but "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town" has endured beyond either. The man who wrote it died toward the end of 2017, and, before the old year fades away, I wanted to tip my hat to a song that has a character all its own. Mel Tillis was a country music superstar and sang a zillion hits in the Seventies - including (for those figuring out how to connect this week's Song of the Week with last week's) an album of duets with Nancy Sinatra. Keely Smith's sometime husband Jimmy Bowen briefly dated Nancy. So that's three degrees of separation from Keely to Mel. Or, if you prefer something a little bit more musicological, it was Bowen who co-produced Nancy's biggest hit duet ("Somethin' Stupid") and hired Lee Hazlewood to produce Nancy, and Hazlewood came up with the idea of getting her to sing a tone-and-a-half down, which gave her that somewhat rawer sound on songs like "These Boots are Made for Walkin'" that made country singers like Mel want to duet with her. So that's what? Four degrees of separation from Charles Trenet's "Que Reste-T-Il de Nos Amours?" to the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Mel Tillis didn't have his first country Top Ten hit until 1968 ("Who's Julie?"). Before then he was just one of a zillion singers making records that never quite broke through. But once in a while a song of his tickled the fancy of a genuine star such as Waylon Jennings ("Mental Revenge") or even Tom Jones ("Detroit City"). And so it was with "Ruby". One day in 1966 Mel was coming home from his songwriting office at the Cedarwood Publishing Company:

I got stuck in traffic. And I had the radio on. And Johnny Cash came on...

It was a Number One country hit from 1958:

And his mother cried as he walked out

'Don't take your guns to town, son

Leave your guns at home, Bill

Don't Take Your Guns To Town...'

Well, you can guess how that turns out: A lesson in what happens when a boy disdains to listen to his mom. For some reason, though, Mel, stuck behind the wheel, found himself singing along with a slight lyrical variation: "Don't take your love to town." And this injunction was directed not to "Son" or "Bill" but to "Ruby".

Incidentally, do you know a lot of Rubys? It's not the most popular girl's name, and yet there are a zillion songs called "Ruby", starting with a movie theme for Ruby Gentry by my old friend Mitchell Parish that Ray Charles made a lovely record of. Then there's Leiber & Stoller's "Ruby Baby", memorably recorded by both the Drifters and Donald Fagen. I just looked up the copyright entry for "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town", and in that year alone (1968) there was another "Ruby", a "Ruby Ann", and famously the Rolling Stones' "Ruby Tuesday" - plus a second "Ruby" song by Mel Tillis, of which more later. The appeal of the name Ruby to songwriters is way beyond the appeal of the name Ruby to prospective parents. Judging from the preponderance of the lyrics, it seems to come freighted with disappointment and doom.

But to return to my question: Do you know any actual Rubys? Mel Tillis did - back in Pahokee, Florida, when he was growing up:

In fact, they lived in back of us in a little house. I used to hear them arguing over there. He was a GI who was wounded in Germany. He met the girl in England, a nurse, and he brought her to my hometown.

Where they argued, incessantly. And the accusations and sneers and shouts and screams carried through the open windows across the yard to the Tillis house. Mel was a teenager, and his mom was cryptic when he asked to know what was happening over there. "He's just a mean old thing," she said. "He's accusing that Ruby of everything in the world. She's a nice girl!"

Later, he came to understand that Ruby's husband had never fully recovered. "I guess his war injuries played hell with their love life," he reflected, "and she was too young for that."

And so Ruby, an English war bride of the 1940s, became Ruby, a bit of collateral and marital damage from a very different war a generation later. And, by the time the Nashville traffic started moving, so was Tillis' song:

You've painted up your lips, and rolled and curled your tinted hair

Ruby, are you contemplating going out somewhere?

The shadows on the wall tell me the sun is going down

Oh, Ruby

Don't Take Your Love To Town...

"Before I got home," he said, "I had that song written." Despite the famous reference to "that crazy Asian war", it's not clear he didn't have Korea in mind. Not everyone was thinking about Vietnam in 1966, and there weren't so many returned veterans as there were by the end of the decade:

For it wasn't me that started that old crazy Asian war

But I was proud to go and do my patriotic chore

Oh, I know, Ruby, that I'm not the man I used to be

But Ruby

I still need your companee...

It's usually "patriotic duty", of course. But "duty" doesn't rhyme with "war". "Chore" does, but it suggests something lesser than duty. A chore is a lot of things, but it's not noble; it doesn't give a man a sense of being part of something greater than himself - quite the opposite, indeed, if your idea of a chore is taking out the trash or tidying your room. Still, the couplet has always appealed to me because it's not only an unusual rhyme, it's an unusual word to find in a popular song: As far as I'm aware, no pre-"Ruby" American standard contains a "chore". Five years later, Stephen Sondheim put it in "Losing My Mind" (where it rhymes with "floor"), but prior to 1970 Tillis pretty much has a monopoly on it.

Yet, in a certain sense, it was obtrusive enough to call attention to itself, and give rise to all kinds of latterday analysis as to whether "Ruby" was the first "anti-Vietnam" song. Back at the Tillis pad that day in 1966, Mel sang it for his wife, who had a more basic problem with it. She pronounced it "the most morbid song I've ever heard." And you can see her point:

It's hard to love a man whose legs are bent and paralyzed

And the wants and the needs of a woman your age, Ruby, I realize

But it won't be long I've heard them say until I'm not aroun'

Oh, Ruby

Don't Take Your Love To Town...

"Paralyzed": There's another lyrical rarity (it rhymes under what Tim Rice described to me years ago as "Lewis Carroll" rules). I can think of it only in "To Keep My Love Alive", Lorenz Hart's last ever song, from the 1943 revival of A Connecticut Yankee: "While paralyzed they got paralysis" (rhymes with "palaces" and "chalices").

"Ruby" is not the most complex song musically. The copy I have to hand comes from a collection called The Four-Chord Songbook (D, A minor, G, C , if you're wondering). And the first ten syllables of that lyric are all on the same note, until he gets to that three-note ascent on "your tinted". But so what? If you want tunes where different words have different notes, go get Jerome Kern. We're in a different vernacular here: verse/hook/verse/hook/verse/hook... And, when I say "verse", I mean three lines each on a single note until they land somewhere at the end.

But as I said: So what? It's a super-effective form of storytelling, especially when the storyteller is as good as Mel Tillis. And there's just enough variety in those verses, too - like the extra syllables in that rat-a-tat-tat "wants and needs" line. Some country-&-western type once told me that that sort of thing comes from Tillis' famous stammer, which he'd had since he was three. His autobiography's called Stutterin' Boy, and the stutterin' only stops when the singin' starts. At any rate, our mutual acquaintance said that Mel found it easier if there were lots of words on short notes. I don't know enough about stammering to speculate on that, but I note that the song's hook elongates the titular "Ruby" to a melismatic three bars. Which is great. Otherwise these country story songs risk getting a bit too close to mere tumty-tumty versifying.

The first to record "Ruby" was Waylon Jennings, a very great talent who made a very ordinary recording that does indeed, per Mrs Tillis, sound merely morbid. Indeed, if you're familiar with the definitive version of this song, it's striking how much seems to have gone missing. The problem with verse-after-verse songs is that they can just chug along and end arbitrarily (in my own modest way, I faced a version of this trap on "The Cat Came Back", which is why, after listening to a zillion versions of it, I decided we needed to put a real, emphatic ending on it). Beyond that, the arrangement has insufficient variation within the verses to hold the attention.

The first hit version - Number Nine on the country charts - was released in February 1967 by Johnny Darrell, who tidies up the end, so you at least know the story's over:

Oh, Ruby

Don't Take Your Love To Town...Don't Take Your Love To Town.

Next up was Roger Miller. And, even though his record is still in spare guitar-man style, you can hear the song in the form we now know it beginning to emerge. In the first verse, Miller isn't just strumming along, as Darrell and Jennings do; his guitar's adding subtler colors to the storytelling - it's the skeleton of the fuller orchestrations that would follow. In the second verse, he makes the slightest of lyrical amendments. Instead of "But Ruby, I still need your company", Miller sings:

But Ruby

I still need some company...

"Some" for "your" doesn't seem a big deal. But it conjures not just a man missing his wife in particular but of someone living in such physical isolation that it denies the possibility of any company: in other words, he can't move on from Ruby to someone else; whoever she finds, he'll still be alone. Roger Miller was too good a songwriter himself ("King of the Road") not to have made this choice consciously.

And then he gets to the final chorus:

She's leaving now 'cause I just heard the slamming of the door

The way I know I've heard it slam one hundred times before...

And for those lines there's nothing underneath him except the drum kit. It's as if he's all alone with just that percussive door-slamming, like a hundred times before - taunting him, pushing a man beyond breaking point:

And if I could move I'd get my gun and put her in the groun'

Oh, Ruby

Don't Take Your Love To Town...

And then at long last a real ending to the song:

Oh, Ruby

For God's sake turn aroun'...

Among those who heard the Roger Miller track was Kenny Rogers. At that time he was part of a group called the First Edition, comprised of fellow members of the New Christy Minstrels. Which these days would be like calling your group the New Confederate Statues. But back in the early Sixties they'd been a big chunk of the highly lucrative folk revival (see here for the general vibe). As the mighty wind of the folk boom died away, the New Christy Minstrels turned to "Chim-Chim-Cheree" from Mary Poppins and other variety-show-friendly fare. Rogers & Co broke away because they weren't allowed to do their own songs, and soon had a Top Five hit with "Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)".

But Kenny thought the group should go country, and Roger Miller's "Ruby" was what he had in mind.

Not everyone was so persuaded. But they had a few minutes left at the end of one recording session and they decided to give it a whirl. Kenny Rogers followed the logic of the Roger Miller version and took it to the next level. As he recalled it, when he taught the number to the group, he put drums in all the way through - "You've painted up your lips, and rolled and curled your tinted hair chick-a-boom-chick-a-boom-chick-a-boom", as he sang. So they thought the percussion was part of the song, and got Thelma Camacho to go heavy on the tambourines. The guitars, meanwhile, are niftier and busier than in any earlier recording, and give a dramatic arc to the song, cranking up the narrative tension. As befits alumni of the New Christy Minstrels, the First Edition had great vocal harmonies (Miss Camacho was operatically trained), and, even though they're really only used for two words, those two words are critical, and are deepened and enriched into one great wail of pain:

Oh, Roo-oo-bee-ee-ee...

And then the coup de grâce - Rogers silences the entire band and sings the rest of the title phrase unaccompanied:

Don't take your love to town.

A man alone in the void of utter desolation and abandonment.

You can say what you will about some of Kenny Rogers' excesses a decade later as a pop-country crossover superstar, but on his game he's a brilliant vocal dramatist, and this drama he conjures better than any of his predecessors did. Likewise, the drumming underneath the slamming-of-the-door couplet - as if going out is all she does, and all he does is sit there hearing slam after slam after slam, like a flimsy flapping screen in a windstorm. And in the final seconds the First Edition take Miller's fine ending and improve on it. First one more harmonized cry of anguish:

Oh, Roo-oo-bee-ee-ee...

And then the closing line from the Roger Miller version:

For God's sake turn aroun'...

But, unlike Miller, Kenny Rogers doesn't sing it, he talks it. As if he's saying it under his breath. As if he knows he's about to crack. As if he's finally got his hands on that gun he was mentioning a couple of bars earlier...

Rogers' interpretation carries the song over from the usual country storytelling to something closer to Les Reed & Barry Mason's "Delilah". It's obviously nowhere as fabulously bombastic as all that Welsh boyo bellowing, but it tiptoes up to the same faintly over-ripe field and calibrates the point at which it halts very adroitly. In fact, it was so real that, unlike Tom Jones cheerfully confessing that "I felt the knife in my hand and she laughed no more", Kenny's mere desire to "get my gun and put her in the ground" was enough to get the single banned from certain radio stations.

Everyone's done "Ruby" since then, but almost all of them - including Leonard Nimoy from Star Trek - are simply covering the First Edition's arrangement. When Frank Sinatra changed the second note of "Why Try to Change Me Now?", the composer Cy Coleman thought about it for a year, and then said "You know what? He's right", and amended the sheet music. So too with Mel Tillis: from the Seventies on, when he sang "Ruby" at the Grand Ole Opry or anywhere else, he'd sing the Kenny Rogers arrangement - with the exception occasionally of that last line where he'd sometimes do a big rallentando and sing "For God's sake turn around" slow and dramatic. But even then I wonder if that wasn't because, with his stutter, it was easier for him than talking the line. At any rate, in every other respect, the First Edition became the only edition of the song.

There have been lyrical variations, of course. Back in the Eighties, I heard the late English actor-musician Gary Holton sing, "It wasn't me who started up that crazy Irish war..." And, like other musical pleas, it prompted some response songs, including one by Tillis ("Ruby's Answer") and another by Dodie Stevens ("Billy, I've Got to Go to Town"). But none comes remotely close to the original.

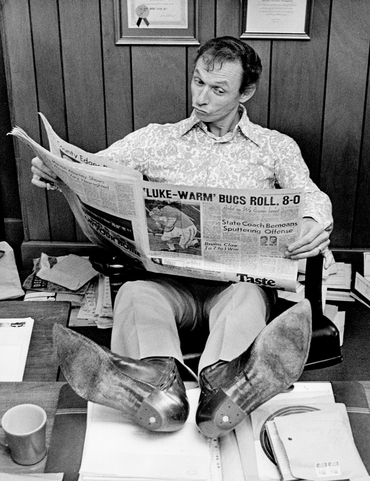

There is, I think, a sort of mathematical formula that applies here: In a more popular war, the scenario would have been a tougher sell; the wife of a crippled veteran is there to support a hero, and there would be far greater general expectation that she would be expected to accept such a role. So "Ruby", a modest country hit in 1967, was a global smash in 1969 - perhaps because, in the three years between Mel Tillis getting stuck in traffic and Kenny Rogers muttering ominously that final line, American perceptions of "that crazy Asian war" had begun to shift. The song was even the beneficiary of a protean music video aired as the closing item one night on NBC's flagship "Huntley-Brinkley Report": As the record played, a camera panned back and forth across an empty marital bedroom - a man who had gone to the other side of the earth to fight for his country, and now his horizons have shrunk to one lonely room from which he cannot escape.

Very moving, I'm sure, but what's it doing on a nightly bulletin of "news"? An Air Force veteran from the Korean War, Mel Tillis had no intention of writing an anti-Vietnam song, but his account of one man's pain, of a war that his own shattered body is trapped in forever, dramatized the human cost far more effectively than any of the more numerous hippie draft-dodger screeds.

As I said, the appeal of the scenario is inversely proportional to the appeal of the war. So what about the couple who inspired the song? A wounded GI from the all but universally acknowledged "good war" and the English bride who'd nursed him, and stuck with him when a spinal operation had gone wrong... The couple a teenage Mel had heard arguing daily in the little three-room house behind the Tillis home in Pahokee, Florida...

"He divorced Ruby," said Tillis, "and married someone else. The ending to this story is that the guy killed himself and his third wife. Very sad."

Too sad, too bleak, too "morbid", in Mrs Tillis' word. So a skilled songwriter leaves the ending uncertain:

Oh, Ruby

For God's sake, turn aroun'...

Oh, and whaddayaknow, the record was produced by Jimmy Bowen, then married to Keely Smith. So that makes no degrees of separation between last week's Song of the Week and this.

~Many of Mark's most popular Song of the Week essays (including the above referenced "Delilah") are collected together in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the special promo code at checkout to enjoy the special Steyn Club member discount.

Also for Mark Steyn Club members: If you disagree with any or all of the above, feel free to have at it in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get your gun and put his assessment in the ground! For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

For a different kind of audio pleasure, don't forget this weekend's Tale for Our Time, a Jack London classic from a far wilder country than Mel Tillis' Nashville: You can find Part One here, and the conclusion here. And join Mark this Friday when he presents the second of our seasonally frosty January stories.