It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas

Ev'rywhere you go...

And that's true. It is. On Stuart Varney's show on Friday I even sang the title phrase, somewhat gloatingly, in reference to this (Theresa May has now set the date for the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union, and it looks like I'll be winning my hundred bucks with time to spare). That would be reason enough to celebrate Meredith Willson, the great son of Iowa who wrote "It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas". But this Christmas marks another landmark event in Willson's life: the 60th anniversary of the opening of his biggest Broadway hit, The Music Man. Six decades ago, just ahead of its December opening at the Majestic on Broadway, the show was trying out in Philadelphia, with much trepidation about whether it was too cornfed for the Great White Way. Chances are if you caught the show in Philly you left the theatre humming or whistling or singing:

Seventy-Six Trombones

Played the big parade!

A classic showtune - big fat words for big fat notes:

There were copper bottom tympani in horse platoons

Thundering!

Thundering!

All along the way

Double bell euphoniums and big bassoons

Each bassoon

Having his

Big

Fat

SAY!

The Music Man is a very unusual Broadway hit because it's not based on anything. Not on a play, as My Fair Lady was. Or on short stories, as Fiddler On The Roof was. Or on a novel, such as Show Boat, or a foreign hit, like Carousel. In an art form almost wholly devoted to the art of adaptation, it's a rarity: an original musical. Even rarer, in an art form founded on the principle of collaboration, The Music Man is a one-man musical: Meredith Willson was not just a Music Man, but a Book, Lyrics And Music Man. That's because, rarest of all, The Music Man is a personal musical, adapted from nothing more than Willson's boyhood in the Iowa of more or less exactly a century ago, with River City serving as a thinly veiled Mason City. Almost anyone else would have written it up as a slim volume of heartwarming rosy-hued reminiscence. But Willson happened to be retailing some light anecdotage to a gaggle of pals one day, and one of them, Frank Loesser, writer of "Baby, It's Cold Outside" and "Once In Love With Amy" and "Two Sleepy People", leapt to his feet in one of those lightbulb moments, and said: "Why don't you write a musical about it?"

It had never occurred to Willson to write a musical about his childhood or anything else, but Loesser was by now pacing the floor and working it all out:

Maybe you can start with the fire chief. Let's make him the leader of the town band. Maybe you can play the fire chief. And maybe instead of a pit orchestra, you can have a real brass band in the pit. And you're the leader of the band. You could also be sort of a narrator and talk directly to the people in the audience. That way you could tell everybody about your town. It would be real Americana!

That was 1949, and boy, did it sound easy. The Music Man eventually opened on Broadway eight years and 32 script drafts and an entirely rewritten score later. But it was still "real Americana" - with a twist: the tale of a con man who comes to town to sucker the hicks but winds up losing his heart instead. And all played out against the composer's own home town memories. "I didn't have to make up anything for The Music Man," said Willson. "All I had to do was remember." He was born in Mason City on May 18th 1902, weighing in at 14lb 6oz - the largest baby ever born in Iowa. Just like Marian the Librarian in the show, his mother gave piano lessons. And there was certainly no shortage of traveling men passing through Mason City in those days: when he came to write The Music Man, Willson found himself recalling a different huckster every time he sat down to conceive "Professor" Harold Hill.

Unlike Hill, who claimed to be a graduate of Gary University, Class of '05, when the university had yet to be founded, Meredith Willson was a genuine conservatory guy. He left Iowa for New York to study at Juilliard, and was only 19 when John Philip Sousa made him first flautist of his legendary band. By the age of 22, he was playing in the New York Philharmonic under Toscanini. At 35, he wrote his first symphony. But the music man was an all-kinds-of-music man. He was also musical director for NBC, he scored Charlie Chaplin's film The Great Dictator and was nominated for an Oscar, and he was a recurring character, a lovelorn bachelor, on the Burns & Allen radio show. He wrote the theme song for "Tallulah Bankhead's Big Show" and most weeks delivered his catchphrase on the air, responding to some query by the star with "Well, sir, Miss Bankhead..."

And, of course, he wrote "It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas", one of those Yuletide hits that started fairly modestly but metastasized over the year. It's a song that sings effortlessly: For a conductor and composer, Willson was a pretty fine lyricist. The words and music are so indivisible it's as if they were conceived simultaneously: not many songs nail the union of the two elements half so well. He could certainly write conventional songs. Yet, for The Music Man, Willson decided to do something a little different. For the music, he went with period flavor - the show is set circa 1912, though the song "Ya Got Trouble" contains a reference to the comic Captain Billy's Whiz-Bang, which didn't get going till 1919. But don't get too hung up on details: River City feels like Mason City would have done somewhere on the cusp of the oughts and the teens. So Willson wrote music of the kind you'd have heard back then - whether Sousa marches, or parlor ballads, or barbershop quartets. "Lida Rose" was so plausible that these days barbershop quartets include it in their repertoire with "Sweet Adeline" and all the other genuine turn-of-the-century stuff. But Willson didn't merely write a pastiche song, he embedded it in a score. Aside from being a lovely barbershop tune, "Lida Rose" is also sung contrapuntally against "Will I Ever Tell You?", just as "Goodnight, My Someone" is a dreamy, slowed-down three-quarter-time modification of "76 Trombones". For a show that's often dismissed as a hokey crowd-pleaser - especially alongside the 1957 season's supposedly more demanding West Side Story - the music is very skilled, and has a real logic to it: Why are "Goodnight, My Someone" and "76 Trombones" essentially two takes on the same theme? Because their respective singers, Marian the Librarian and Professor Hill, have, as Willson put it, "something more in common than meets the eye" - even if it takes them a while to figure it out.

But the triple-threat author saved his greatest innovation for the lyrics. The songs relied not so much on rhymes, as on a kind of rhythmic dialogue. Here's the opening number, the train crossing into Iowa, and the traveling men gabbing away:

Cash for the noggins and the pickins and the frickins

Cash for the hogshead cask and demijohn...

And then the conversation turns to Harold Hill:

He's a music man.

He's a what? He's a what?

He's a music man and he sells clarinets

To the kids in the town...

Set to the clicketty-clack of the train chugging down the tracks, it's a kind of vernacular recitative. Willson wasn't anybody's idea of a revolutionary, but on Broadway this was distinctive and very effective. Motoring through Iowa a decade or so back, Slate's "Chatterbox" columnist, Timothy Noah, went so far as to propose Willson's rhythmic dialogue as the progenitor of rap:

White people stole rock'n'roll and jazz and nearly every other indigenous form of popular music from blacks, and the black community is right to be annoyed about that. But Chatterbox invites readers to consider that African-Americans exacted revenge by stealing rap music from Meredith Willson, possibly the whitest man who ever lived.

Well, the Tony Awards ran with the jest a couple of award shows ago, and it was kinda cute. But, whatever its broader claims, in The Music Man "Rock Island" was fresh. Almost every musical challenge presented to the composer was resolved in a novel way – a sung-dialogue scene played out against a child pianist practicing his scales, for example. Best of all were the big setpieces for Harold Hill, memorably played on stage and screen by the wonderful Robert Preston, a very distant umpteenth choice for the lead after everyone from Danny Kaye to Gene Kelly had declined the show. Hitherto, Preston had mostly played Hollywood bad guys, and the producers were worried his singing voice wasn't strong enough. But at auditions they used "Ya Got Trouble" and, unlike the trained singers with the big voices, Preston got it. It's a perfectly musicalized salesman's patter:

May I have your attention, please

Attention, please!

I can deal with your trouble, friends

With a wave of my hand

This very hand...

There were more lyrical moments for Professor Harold Hill. This is one that always reminds me of my own childhood. My father loved the Music Man cast album and he pretty much wore out the LP. Whatever room of the house I was in, you could hear this playing from some distant corner. And, if Robert Preston wasn't singing it, my dad usually was, while shaving or putting on a pot of tea:

Gary, Indiana

Gary, Indiana

Not Louisiana

Paris, France, New York or Rome

But Gary, Indiana

Gary, Indiana

Gary, Indiana

My home, sweet home...

It's a simple jingle with a very clever shift of emphasis in the recapitulation of "Indiana" that's just enough to keep it interesting. I remember a Marvel comic around that time – was it Spider-Man or Daredevil? – and whichever superhero it is is sitting around in his civvies pickin' an' a-grinnin' on the guitar::

Gary, Indiana

Gary, Indiana...

Mary Jane or Gwen Stacy or whoever the gal was comes up and says slightly mockingly, "Hey, hot licks from The Music Man. Cool." It was never cool; indeed, it was the very antithesis of cool. But it put Gary, Indiana on the map. New York, New York may be a helluva town, and Chicago my kind of town, but for millions who'd never been anywhere near the place, Gary, Indiana was the most mellifluous burg in America's musical gazetteer. Some years ago, I got to visit it for the first time. "What's it like?" asked my dad. "It's the murder capital of America," I said.

He refused to believe it. In his and a million others' minds, in Gary, Indiana, it's always 1905 and Harold Hill is about to graduate from a conservatory of music that does not yet exist. In a score with such a pleasing unity, critics faulted only one number – the love ballad. "The only jarring lapse in musical fidelity," wrote Gerald Bordman in his great study of Broadway, "was the show's most popular love song ...which had a distinctly late thirties or early forties sound", he added sniffily:

There were bells on the hill

But I never heard them ringing

No, I never heard them at all

Till There Was You...

I can see Bordman's point: It's in classic mid-century AABA form – main theme, reprise, middle section, back to main theme – which wasn't common in 1912, in Iowa or anywhere else. But in form, like "Iowa Stubborn" or "Rock Island", it has a character all its own. Like the patter, it's not big on rhyme. There's really only one, held over (like "your step" and "doorstep" in "Sunny Side Of The Street") from one section to the next. That "ringing" from the first A passage is finally rhymed in the second:

There were birds in the sky

But I never saw them winging

No, I never saw them at all

Till There Was You...

And then wrapped up in the finale:

There was love all around

But I never heard it singing

No, I never heard it at all

Till There Was You!

And in between comes an entirely unrhymed middle section:

And there was music

And there were wonderful roses

They tell me

In sweet fragrant meadows

Of dawn and dew...

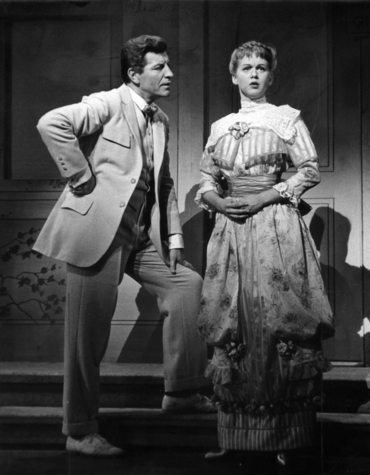

Which doesn't look like much on paper but sings just beautifully. It fell to Barbara Cook to introduce the song as Marian the Librarian, and it's hard to believe it was not written with her bell-like lyric soprano in mind. Miss Cook's voice darkened over the years, and she became a sophisticated interpreter of more nuanced material - as her obituarists noted when she died in August. But, if you were at the Majestic on Broadway in 1957, the name Barbara Cook will always evoke the translucent trill of the original "Till There Was You". When the film rights were sold, Meredith Willson insisted it was Robert Preston or bust, but the leading lady's part went, as they often did in those years, to Shirley Jones – a state of affairs Miss Cook alluded to many years later in an autobiographical number about a Broadway "Ingenue":

And movie roles she moans to do

They give to Shirley Jones to do...

But Shirley did it very well, pealing "Till There Was You" with touching sincerity.

Meanwhile, four thousand miles away from River City, in Liverpool, a young lad called Paul McCartney was just getting into rock'n'roll. But his cousin, Bett Robbins, was into Peggy Lee and, on her occasional babysitting nights with Paul and his brother, it was Bett who controlled the Dansette. Paul ended up developing quite a taste for Peggy Lee, as did John Lennon, who couldn't stand Sinatra but thought Peg was a different kettle of fish. In 1961, her single of "Till There Was You" was a modest hit on the British charts, and Paul thought it was just another great Peggy Lee record. I sat next to him once at a British songwriters' get-together and, in an effort to avoid more problematic conversational topics such as "Mull Of Kintyre" or "Wonderful Christmas Time", I asked him about "Till There Was You". He said he'd had no idea until years later that it was from The Music Man, but he liked the simplicity of the song and of Peg's arrangement. And so, when the Beatles auditioned for Decca Records a few months later, "Till There Was You" was one of the numbers they offered. They didn't get a contract, but they kept the song in the act at the Star Club in Hamburg.

As fans know, the Fab Four recorded several non-rock numbers - "Ain't She Sweet", "My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean" - but they were kind of before the Beatles really became the Beatles. They also did "Moonlight Bay" on the telly with Morecambe & Wise, complete with Eric in moptop yelling "Yeah yeah yeah". But "Till There Was You" is different: Meredith Willson's show tune for an Iowa librarian appears on With The Beatles side by side with "All My Loving" and "I Wanna Be Your Man" and the only other "covers" are Motown and early rock'n'roll ("Please, Mr Postman", "Roll Over Beethoven"). It was released in Britain and Canada in November 1963 and that year they performed it before the Queen at the Royal Command Performance.

The US had to wait for Meet The Beatles, which was issued at the end of January and also included "Till There Was You" - which they sang on their American TV debut with Ed Sullivan. I find it one of the most appealing tracks on the album: Paul McCartney's voice is sweet and unaffected and true. It still is on that kind of material. I remember listening to his recent standards album Kisses On The Bottom and, when he sang "Home (When Shadows Fall)", tears welled in my eyes, and not just because the lawyers' bill had arrived. The Beatles' "Till There Was You" is really a cover of the Peggy Lee record, but George Martin keeps it very spare: acoustic guitars and Ringo on restrained bongos. Paul's vocal is sincere and affecting. In his best songs from immediately afterwards – "Yesterday", "Here, There And Everywhere" – he seems to be striving for the simplicity he found in "Till There Was You". It's the only show tune ever recorded by the Beatles and, if you think that's just 'cause an executive suit at Parlophone made them cover it, think again: It's still in Paul's act 60 years later.

As for Meredith Willson, after years as conductor, arranger and Tallulah Bankhead's second banana, he looked set for a grand reign as Broadway's music man. There was a second musical, The Unsinkable Molly Brown, and a couple of other things. But lightning didn't strike twice. Every so often, someone comes along with just one show in them and they pour it out, and then that's it. When Jonathan Larson died on the eve of Rent's opening in the Nineties, the papers were full of Broadway professionals mourning what might have been, all the other musicals he would never go on to write. But Rent, for which he wrote book, music and lyrics, felt as personal to Larson as The Music Man was to Willson: two different worlds, but in each case it was the only one the author knew, the only story he had to tell. The Music Man is beloved by high schools and summer stock, and will sing as long as any "Americana" does. And in my mind's ear I always hear a strange mélange, Ringo's bongos and a Shirley Jones/Barbara Cook voice:

There were bells on the hill

But I never heard them ringing

No, I never heard them at all

Till There Was You...

~Many of Mark's most popular Song of the Week essays are collected together in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promo code at checkout to benefit from our special member pricing.

Also for Steyn Club members: If you disagree with any or all of the above, feel free to let rip in our comments section, where we always appreciate Trouble with a capital T, and that rhymes with C, and that stands for Club: As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get to it! For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our new Gift Membership.

Please join Mark for a different kind of audio pleasure this Friday when he starts a brand new Tale for Our Time, our monthly series of nightly audio adventures.