Twenty years ago - October 31st 1997 - a pair of actors emerged from Seneca Creek State Park in Maryland and were taken to the local Denny's for their first full meal after eight days in the woods living on Power Bars and bananas. They had been filming a "naturalistic" horror film, and described how "surreal" it felt to return to the real world and be surrounded by booths of people dressed in Halloween costumes.

And thus did one of the most unusual of all movie shoots wrap.

It's hard now to recall how huge this thing was upon its eventual release in 1999. I remember hoping London's film critics would decline to roll over in the face of the juggernaut, but if anything they loved it even more than the US reviewers, whose enthusiasm derived mainly from a fear of being wrong-footed by a surprise hit. "Low-budget" hardly begins to cover it: The film cost $60,000, or $50,000, or $35,000, according to which paper you read, and made $135 million in its first nine weeks, or $150 million in its first three months, or whatever. In fact, the original budget was less than 25 grand and it grossed over a quarter of a billion - which makes it the biggest indy hit ever. It was also supposed to herald a whole new school of film-making.

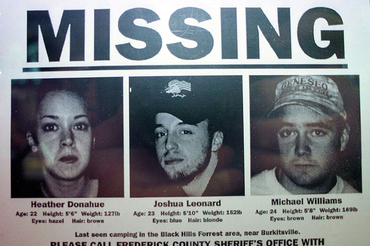

The premise of The Blair Witch Project is explained in the card that pops up on screen right at the beginning: three students making a documentary disappeared in the Black Hills of Maryland; the footage we're about to see was found in the woods. People thought this was real - that three actual human beings were dead. IMDB - the Internet Movie Database - listed the actors as "deceased", a genuine error that nobody bothered to correct. Actress Heather Donahue's mother received sympathy cards offering condolences on the loss of her daughter.

All of this derived not from the film but from a website that the movie's directors had created to jump-start a canny online campaign peddling the "reality" of what had happened. It went, as nobody said back then, viral. Anyone can make an independent film, but The Blair Witch Project was a pioneering example of independent hype. Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick were a couple of film students (in their thirties, as an even higher proportion of students are today) who had no money to make a movie. So they hit upon a gimmick which would obviate the need for any dough — a plot about a trio of student film-makers who head off to make a documentary about a spooky old legend — the Blair Witch — with two cameras (one color, one black-and-white), and wind up getting lost in the woods while some creepy, unseen force leaves unusual arrangements of twigs outside the tent.

A cheap and cheerful premise. So they sent out a casting call:

An improvised feature film, shot in wooded location: it is going to be hell and most of you reading this probably shouldn't come.

Those who did walked into the room to be told: "You've been in jail for nine years. We're the parole board. Why should we release you?" The cast that survived this process was Heather Donahue, who plays "Heather Donahue", Joshua Leonard, who plays "Joshua Leonard", and Michael C Williams, who plays "Michael Williams" sans middle initial. They were told to take the cameras and sound equipment into the woods and improvise dialogue while the directors blasted spooky noises from boomboxes in trees, and then left instructions for the next day's shoot in milk cartons secreted about the undergrowth. The result is a horror story with no gore, no monsters, no scary music, just lots of wobbly, shaky hand-held camera shots of trees and ground and sticks and stones and the inside of the tent.

It's a kind of cinematic version of Greek tragedy — terrible bloody things are happening off-stage but all we see onstage are people standing around talking. The big difference, of course, between Sophocles and Blair Witch is the considerably more limited vocabulary:

Mike: This is some of the weirdest f**ked up craziest sh*t...

Josh: Like totally f**ked up...

Mike: I don't even want to think about this sh*t...

Heather: When we're out of here, we'll totally laugh about this sh*t...

And on, and on, and remorselessly on. It occurred to me about 20 minutes in that, if they were, indeed, being stalked by a Blair Witch, she was most probably an aggrieved 1950s schoolmarm tired of listening to all this swearbox-busting totally f**ked up sh*t. I appreciate that the above had a certain verisimilitude two decades ago, and even more so today. I understand too that most people do not talk like Oscar Wilde, and that the seemingly naturalistic accessories of contemporary motion pictures have made the heightened articulacy of old-school drama seem unduly artificial. And I get that the characters are meant to irritate each other and, to some extent, us too. But they do so in such a generic, moronic way that you're mainly irritated by the irritatingly lazy way they're trying to be irritating. Nor is the sense of supernatural terror aided by such prosaically earthbound grunting.

That said, at its heart The Blair Witch Project is about something real: North America is mostly a thin strip of civilization clinging to a wilderness. You wander off behind the ugly strip mall, and suddenly you're in mile upon mile of dense forest and your cellphone no longer works. The things "Heather", "Josh" and "Mike" do are no sillier than what thousands of city dwellers hiking in the wilds do every day of the year. Yet, speaking as a North Country woodsman, I found the film's supposed "reality" something of a tough sell. It's very obvious that the picture's not been filmed deep in the forest, but that they're just tramping about on the edge: there's too much light, too much sky; there's not that claustrophobia you get, that sense of the branches closing above you and the trees swallowing you up. I'm sure the directors had very good reasons for this: the gloom of dense foliage overhang would become oppressive on screen. But they should have at least been able to convey some feeling for the contrasts of the landscape — the thickets and clearings, the dark northern slope of a wooded hill, the sudden shafts of sunlight, the liberating airiness when you stumble across a pond. As it is, the physical landscape of this picture is contrived and constrained and, as the landscape's all you have to look at, that impacts the picture's ability to persuade.

Today only one of the trio (Josh Leonard) is a working actor; Mr Williams is a guidance counselor and Miss Donahue a grower of medical marijuana. The two directors' presence in the business has been equally precarious, although, given the return in investment, neither needs the work. Still, The Blair Witch Project was meant to be a harbinger of a decentralized freelance film industry to come in which any old Joe Schmoe could be his own 20th Century Fox. I remember having lunch with a very famous film director who loathed Blair Witch and even more what it portended. "This is the end," he sighed, toying with his arugula. "David Lean? We're never going to see a Lawrence of Arabia again."

That's not exactly how it turned out. True, there's no David Lean. But the films are bigger than ever, with the multiplexes kept alive only by tedious, gazillion-dollar, 3D CGI battle scenes of seventy-year-old superhero franchises. Even the so-called "independent" pictures have to have big enough budgets to enable Harvey Weinstein to pay off the starlets. Blair Witch, as its thousands of non-viral imitations have proved over the last decade and a half, was a fabulous one-off. The plot is perfunctory, the characters cyphers, there's minimal sense of place, but the conceit underpinning it all is ingenious, and the brio with which the creators advanced a barely-existing project was very savvy - not least in the way they played the inverted snobbery of film critics like a Stradivarius. A couple of guys spent 25 grand with more skill than a bunch of Hollywood execs burning through a quarter of a billion. Which, if not a victory for storytelling, is at least one for book-keeping.

~If you disagree with Mark's movie columns and you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, then feel free to have at it with a Steyn Bitch Project in the comments. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates.

If you're in the mood for less visual storytelling on a Saturday night, Mark will be back later this evening with the final episode of our current Tale for Our Time, Anthony Hope's classic adventure The Prisoner of Zenda. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, see here - and don't forget our new gift membership. And do join us on Monday for a live Clubland Q&A, and on Tuesday for a Halloween bonus Tale for Our Time.