This last week we've been marking the 40th anniversary of the death of Elvis Presley, with a look at early Elvis, mid-period Elvis, and dead Elvis. To round our our series, I thought we'd celebrate the biggest hit song supposedly written by Elvis:

These days more or less every pop star is expected to come up with his own songs. It wasn't always that way: Once upon a time, songwriters wrote songs, and singers sang them. Very occasionally, a singer ventured onto the writer's turf: Frank Sinatra genuinely wrote a handful of songs, including the much covered "This Love of Mine", and made a significant enough contribution to the even more covered "I'm A Fool to Want You" that Joel Herron and Jack Wolf insisted he be given a co-author's credit. In a looser age of pop composition, surely then Elvis Presley, coming midway between Frank and the self-composing Beatles, must have penned a ditty or two over the years?

Well, like Sinatra, Presley had a house composer in his bodyguard. Frank's muscle was Hank Sanicola, a music-bix jack-of-all-trades who served as Sinatra's co-writer on "This Love of Mine" and his Christmas song "Mistletoe and Holly". Presley's muscle was a guy called Red West. (Red died just last month, and, for a dilettante songwriter, he did a pretty good job on a late-Elvis number called "If You Talk in Your Sleep".) One day in 1961 Elvis said to Red, "How about coming up with a song called 'That's Someone You Never Forget'?" He was thinking about his mother, Gladys, who'd died a couple of years earlier. Red did most of the rest of the work, but a good title is half the song, so Red gave Elvis 50 per cent of the credit. The gospel-ish record isn't bad but they sat on it and only released it as a B-side six years later.

A few months after "That's Someone You Never Forget", Elvis had another idea for a song. He'd had a big hit in 1960 with "It's Now or Never" - which is, of course, "O Sole Mio" with new lyrics. So he figured it would be fun to do that again, and he had the perfect song: "Begin the Beguine." "I like the melody," he told Red West, "so let's put new words to it." Unfortunately, unlike "O Sole Mio", "Begin the Beguine" wasn't written by long-dead foreigners, but by Cole Porter, who in 1961 was alive and well-ish - and certainly well enough to tell an impertinent pelvis-waggling whippersnapper to go take a hike for even suggesting that one of the greatest standards in the American Songbook might benefit from having its blithe, sophisticated lyric replaced by some rock'n'roll grunting.

So Elvis was back to square one, and decided to write his own "Begin the Beguine" from scratch, co-opting Red West and another member of the "Memphis Mafia", Charlie Hodge. "You'll Be Gone" had exotic Latin rhythms and Spanish-style guitar, and Elvis was pretty pleased with it. So, when the teenage Priscilla came to visit from Germany, he proudly played her his brand new composition. She replied that she preferred his rock'n'roll stuff. Elvis flew into a rage, and never wrote another song.

So what does that leave? Well, if you pick up almost any Elvis Greatest Hits compilation, you'll find:

Love Me Tender, love me sweet

Never let me go

You have made my life complete

And I love you so...

Words and music by Vera Matson and Elvis Presley.

So who wrote what?

Answer: Neither of the above.

The tune for "Love Me Tender" was by Geo. R. Poulton.

Geo. R. who?

He was born in 1828 in Cricklade, a modestl settlement between Cirencester and Swindon in Wiltshire. It's the first town on the Thames as it flows down to London. When the boy was seven, his family emigrated to America, and George was raised in New York state in the village of Lansingburgh, which is now part of the city of Troy. So Troy gave us two protean artifacts of 19th century American pop culture - "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" (first published in The Troy Sentinel) and George Poulton's most famous tune. Just for the record, Herman Melville wrote two novels in Lansingburgh, but neither was Moby Dick. Whereas Mr Poulton spent his entire adult life in the area. As a schoolboy at Lansingburgh Academy, he began organizing local concerts, and proved a popular pianist, violinist, singer and conductor, and pretty soon his reputation spread and publishing houses in New York City and elsewhere began picking up works like the "Albion Polka" and the "Linwood Waltz".

Somewhere along the way he set a poem about a "maid with golden hair" by "W W Fosdick, Esq", as the sheet music credited him. That's not "esquire" in the contemporary British sense of gentleman (or, in 19th century precedence, as denoting the rank between a gentleman and a knight), but in the American usage of attorney. Fosdick was a Cincinnati lawyer, but with a theatrical background on his mother's side. By the 1850s, he had published anthologies of his poetry. By 1860, his law practice was sufficiently lucrative that he could launch an illustrated periodical in Cincinnati called The Sketch Club. The following year he wrote what would prove to be his most famous words:

When the blackbird in the spring

On the willow tree,

Sat and rocked, I heard him sing

Singing Aura LeaAura Lea, Aura Lea

Maid with golden hair

Sunshine came along with thee

And swallows in the air...

Dedicated to S C Campbell of Hooley and Campbell's Ministrels, the song was written for minstrel shows but is of a quality far transcending the genre. Indeed, the beauty of George Poulton's lovely, lyrical setting of Fosdick's words was one of the few things Americans agreed on in the turbulent years after its composition. It was popular with both Union and Confederate troops, and in 1865, a few weeks after the end of the Civil War, the graduating class at West Point sang Poulton's beloved tune with new lyrics:

We've not much longer here to stay

For in a month or two

We'll bid farewell to "Cadet gray"

And don the "Army blue"

- which just about fits, except for the awkward prosody on the word "cadet". How did W W Fosdick feel about this change of text? Well, we'll never know. He was long gone, having died aged 37 in April 1862 and thus never seeing the end of the war, or knowing that his would be one of the few songs of the era to retain its popularity in the decades after. To be sure, the story of "Aura Lea" is that of an indestructible tune to which endless lyrical variations have been set, but I confess a certain affection for Fosdick's somewhat over-ripe effusions:

In thy blush the rose was born

Music when you spake

Through thine azure eye the morn

Sparkling seemed to breakAura Lea, Aura Lea

Birds of crimson wing

Never song have sung to me

As in that sweet spring...

Wouldn't you rather trust your daughter to a young swain coming a-courting with those words on his lips than some coarse blackguard braying that he's going to treat her body like a "drive-thru"? Whoa, not so fast. The composer of "Aura Lea" was not such a demure wooer as his lyricist's words might suggest, or the sheet-music illustrations of him as a fey daydreamer with shoulder-length poetical hair. George Poulton was a popular music professor in upstate New York, but something of a rake and a cad where his lady students were concerned. And, after one such affair, according to Kathleen Tivnan of the Lansingburgh Historical Society, he was dismissed from his job for "conduct unbecoming of a teacher". A few days later, the girl's outraged family exacted their revenge by seizing Poulton and tarring and feathering him on the banks of the Hudson River. The loss of income and reputation affected his health, and he died in disgrace at the age of 38 in 1867.

But his song endured. College glee clubs and barbershop quartets sang it for a century - although I was a little surprised when, a couple of years ago, my youngest kid's music teacher assigned it to the grade-school chorus. While he was practicing it at home, I said, "Don't you know the Allan Sherman version?" Sherman was America's most tireless song parodist ("Hello, Muddah, Hello, Faddah", "(It's very clear) Your Mother's Here to Stay", "Beautiful Teamsters", etc) and had a one-verse version of "Aura Lea". My wonky memory recalled it as:

When they take your temp'rature

Take it orally

That's because the other way

Works more painfully.

But in fact, when we got a-Googling, it turns out Sherman wrote:

Ev'ry time you take vaccine

Take it orally

As you know the other way

Is more painfully.

Which makes perfect sense: Sherman penned his version shortly after Jonas Salk's breakthrough polio vaccine. Vic Damone delivered a lovely rendition of "Orally" on The Dean Martin Show.

In 1956, the year after Dr Salk's vaccine hit the big time, an unrelated phenomenon was doing likewise: Elvis Presley had been signed for his first motion picture - and this wasn't one of those viva-Acapulco-fun-in-Las-Vegas vehicles from his post-army phase: this was a bona fide historical drama with Presley, for the first and only time, in period costume. The film was a bit of cheapo B-picture filler called The Reno Brothers and the part of the youngest of the quartet had been turned down by several likely lads, including Robert Wagner. And then suddenly Elvis was inserted into the action and the role got bulked up extensively. His three siblings are all cavalrymen in the Confederate Army, topically enough, but young El is too much of a wee nipper to wear his secessionist nation's uniform, and so has to stay home. Which is just as well, otherwise today Antifa would be tearing down the King's statues all over Vegas and Memphis.

The oldest brother Vance (Richard Egan) has a sweetheart called Cathy (Debra Paget). Word comes from the distant front that Vance has been killed in battle, and back at the farm his betrothed grieves. But eventually Cathy agrees to wed the only Reno brother still around, young Clint (played by Elvis). Unfortunately, it's all a big mix-up, and Vance is not deceased. So he is somewhat surprised, when the three siblings return from soldiering, to find that his girl is now married to his kid brother. This creates some tension in the household, although Vance does his best to stiffen his upper lip: "We always wanted Cathy in the family", etc. Alas, Cathy is very obviously still in love with Vance, notwithstanding that Clint is played by Elvis Presley.

Complications ensue. But the basic plot premise is made more convincing by the fact that Debra Paget was genuinely antipathetic to Elvis, being in love with Howard Hughes at the time. She expected the rock'n'roll sensation to be a moron and described herself as "quite surprised" that he wasn't - but, alas for the Pelvis, insufficiently surprised to give him a tumble, and instead leaving down at the end of Lonely Street for the duration of the shoot.

You don't cast Elvis in his first movie and then not let him sing. But sing what? It's set in the Civil War, and they didn't have blue suede shoes back then, so a hip-swiveling rocker'll stick out like a sore hip - as it does when Clint sings "We're Gonna Movie" on the Renos' front porch. A period number would seem the obvious choice, and "Aura Lea" is certainly among the most beguiling. But do Elvis fans really want the King warbling all those flowery inverted-order lines like "Yet if thy blue eyes I see/Gloom will soon depart"? So it was decided to give "Aura Lea" a makeover - and fortunately, unlike Cole Porter, Messrs Poulton and Fosdick were no longer around to object. Of course, the clever trick of the rewrite is how adroitly it straddles both the period and the au courant:

Love Me Tender, love me true

All my dreams fulfill

For my darling I love you

And I always will...

It's an unlikely song for the 1860s ("dreams" coming true belongs to a later pop vernacular), but it has the whiff of a more genteel era of courtship than "Wear My Ring Around Your Neck" - that "for", for example, in "For I love you..." Very nice.

So who re-wrote "Aura Lee"? Step forward, Ken Darby. He was born in Nebraska in 1909, so he was no rock'n'roller, but a talented mainstay of the music world. A fine choral arranger, he had a group called the Ken Darby Singers, who backed Judy Garland in a studio album of the Wizard of Oz songs in 1940, and two years later sang with Bing Crosby on the original single of "White Christmas". On the radio, he provided the music for "Fibber McGee and Molly", in which capacity he performed a version of "'Twas the Night Before Christmas", his first point of contact with those two great cultural contributions from the Troy area. He was Marilyn Monroe's vocal coach on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and there are certainly worse ways of passing your time than getting up in the morning and going to work to spend the day teaching Marilyn how to sing "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend". And by the time he was done he had three Oscars on his shelf, for scoring The King and I, Porgy and Bess and Camelot.

The Reno Brothers project was just another day at the office for Ken Darby. Told that they needed a Civil War song for the picture, Darby picked out five ballads from the early 1860s and played them for Elvis. "Aura Lea" was the third or fourth. "This is the one," said the singer. So Darby set about turning "Aura Lea" into "Love Me Tender", and did it very expertly. Unlike Mr Fosdick, he imposed a song form on the tune - nothing too obtrusive, just that two-thirds echo of the title: "Love Me Tender, love me sweet"... "Love Me Tender, love me true"...

Love me Tender, love me long

Take me to your heart

For it's there that I belong

And we'll never part...

All that "love me" repetition could get a bit boring, except that they alternate between the low notes of Poulton's verse ("Love Me Tender, love me long") and then the high notes ("Aura Lea, Aura Lea") of the chorus ("Love Me Tender, love me dear"), which gives a real ache and intensity to the reprises. It's very deftly organized. And I doubt that Ken Darby thought it was anything more than just a solid professional job that served the needs of the picture.

Elvis' manager, Colonel Parker, looked on it a little differently. His boy was a raucous rock'n'roller, but this movie song was going to be his first mainstream love ballad, and Parker thought that would be a big deal with the public, and potentially very lucrative. "Aura Lea" was out of copyright, so they didn't have to pay Poulton and Fosdick anything ...or even mention them. And, if nobody knew who wrote the song, why couldn't Elvis have written it? So, when they heard Ken Darby had rewritten "Aura Lea" into "Love Me Tender", the Colonel and the Aberbach brothers, who ran the Presley music publishing operation Hill & Range, politely informed Mr Darby that they'd be publishing the song and that in addition Elvis would be getting a credit as co-author.

Darby didn't mind, because 50 per cent of an Elvis record still works out better than 100 per cent of a Ken Darby Singers record. But there was a problem. American songwriters have two copyright collection agencies, Ascap and BMI, the latter of which was founded in opposition to the former's monopoly. Broadly speaking, Ascap had the Broadway and Hollywood writers, and BMI had the country & western and rhythm'n'blues guys. Elvis had been signed up as a member of BMI, whereas Darby, being a motion picture composer, was Ascap. And in those days it was not permitted for an Ascap writer and a BMI writer to share credit on the same song. So Darby risked losing his 50 per cent of "Love Me Tender" to a non-writing writer who'd contributed precisely 0 per cent to "Love Me Tender".

Happiness lies/Right under your eyes, as they sing in "Back in Your Own Backyard", and so it proved for Ken Darby. He signed up Mrs Darby - Vera Matson - as a member of BMI, and gave her his 50 per cent of the song.

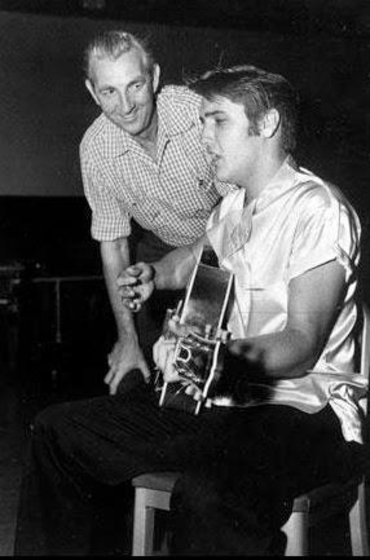

Credit where it's due, though. The studio decided they didn't want Elvis' band (Scotty Moore, Bill Black, DJ Fontana) on the soundtrack, so Ken Darby brought in his own trio (Vita Mumolo on guitar, Charles Prescott bass, Red Robinson drums). But he was impressed by the way Presley took charge in the studio: "Elvis has the most terrific ear of anyone I have ever met," he said. "He does not read music, but he does not need to. All I had to do was play the song for him once, and he made it his own! He has perfect judgment of what is right for him." "What is right for him" turned out to be something the wailing Elvis of "Heartbreak Hotel" had never done before on record. On Wednesday August 22nd 1956 Colonel Parker's secretary, Trudie Forsher, wrote in her diary:

At 10.00 am Colonel Parker calls me to report to music director Mr Ken Darby's bungalow where Mr Presley is rehearsing the song he sings in 'Love Me Tender'. The Colonel arrived,Elvis and his cousin Gene also entered. When I came into the bungalow,standing next to the grand piano with Mr. Darby playing - with his head back and thick dark hair tumbling over his eyes Mr. Presley was oblivious to those around him. Soon the bungalow was filled with Elvis' strong voice singing the most beautiful ballad, I thought. He was dressed in his favorite dark gabardine slacks and blue sports shirt with turned up collar,open at the neck,Mr Presley likes freedom in his shirts-he needs the room to move around. One broad horizental white stripe was around the shirt and across his chest accentuating Mr. Presley's naturally broad shoulders.

Okay, enough about the shirt and shoulders; the key point is "the most beautiful ballad". And Elvis dialed back that "strong voice" on the day of the recording. A friend of his, the actor Dennis Hopper, chanced to be present:

He invited me out to the studio, It was at 20th Century Fox,and I went out and he recorded 'Love Me Tender',and it was really strange because I was standing about five yards away from him,and he was singing into a microphone and I couldn't hear him. I thought how strange it was,and I thought well maybe he's not really doing anything ...cause I was standing a way behind him,and then he asked for a playback and his voice came out - 'Love Me Tender..' - and I thought 'Wow!' How strange! I knew so little about music, it was a different world to me ...that he could be actually recording something that would come out that clearly, and yet I was like in touching distance, practically, of him and I couldn't hear his voice.

That was the key to it: not "The Wonder of You", but a soft, understated rendition of a simple, translucent song. As Elvis would tell friends, "A lot of people thought all I could do was belt." Trudie Forsher again:

The guitar around his broad shoulders, he leaned towards...

Okay, enough with the broad shoulders. How about the song? Dennis Hopper wasn't alone; nobody present had really heard it. So Elvis ordered a playback. And at the end, according to Miss Forsher:

There was a stunned silence, Elvis was satisfied, So was Lionel Newman, so were Ken Darby and the King's Men. As the playback ended, there was an awed silence. Then Ken Darby, the quartet and the old 'pros' in the orchestra broke into spontaneous applause. All at once I heard a torrent of words. 'Great','Terrific','Tremendous'. Elvis smiled his thanks, he was sincerely humble, but he appreciated this reaction, coming from the people who knew music well.

On September 9th 1956, during a break in the shoot, the singer flew back to New York to appear on "The Ed Sullivan Show". He sang "Love Me Tender", and generated enough advance orders that RCA, for the first time in the history of the recording industry, had a million-seller and a gold record before the track was even released. Back in Hollywood, 20th Century Fox hastily changed the name of the movie from The Reno Brothers to Love Me Tender. By November, when the picture came out, "Love Me Tender" was chasing the double-A-sided "Hound Dog" and "Don't Be Cruel" up the charts to make Elvis the first singer ever to occupy the top two positions on the Billboard Top 40. When "Love Me Tender" succeeded "Hound"/"Cruel" at the top of the hit parade, it marked the first time any performer had had two consecutive Billboard Number Ones (the Beatles did it next, then Boyz II Men). Elvis' first non-rock ballad had massively expanded his appeal.

For a simple song, "Love Me Tender" remains oddly elusive for the many other singers who've attempted it. Sinatra's version, with a Don Costa arrangement on his Trilogy set in the Seventies, is pretty insipid, and not as memorable as his first crack at the song - on TV in 1960. Frank's ABC Timex specials had underperformed in the ratings, so someone had come up with the idea of getting Frank and Elvis on screen together for Presley's first appearance after two years in the army. To pull this off, they'd been obliged to give Colonel Parker 125 grand, a then unprecedented amount, especially considering that in exchange for that eighth of a million the Colonel would still not permit Elvis to be on camera for more than six-to-eight minutes max.

Nevertheless, this was one of the incompetent Parker's better deals, at least compared to the pitiful price he sold Presley's masters for in the early Seventies: As Frank's daughter and Elvis' sometime girlfriend, Nancy Sinatra, often says, the best advice her dad ever gave her was always to own your own masters (as he did). In 1960, Parker was looking to land Presley a little of the Sinatra action, and pitch him to a more adult audience so that, post-army, he wouldn't be vulnerable to eclipse by whoever next week's teen idol was. By that measure, the show worked, and was a ratings blockbuster. But the terms the Colonel painstakingly demanded lends a cramped and wary atmosphere to the Sinatra/Presley summit. It's standard variety-show stuff: Frank shrugs his shoulders to the rocky vamp and then Elvis is supposed to gyrate his pelvis but forgets to do it, so Frank does his pre-scripted line anyway - "We work in the same way, only in different areas." And then Frank sings one of Elvis' songs, and Elvis sings one of Frank's. So there's a finger-snappy "Love Me Tender" punctuated by a rock'n'roll "Witchcraft", both arranged by Nelson Riddle and concluding with an a cappella harmonization:

For my darling I love you

And I always will

- in the middle of which Frank interjects "Man, that's pretty." Which it would be if Sinatra had worked on it the way he would have with Ella or Dinah and if Colonel Parker weren't running the clock and wrapping up the medley in a minute and a half.

Nine years later Elvis offered his final version of "Love Me Tender", for the film The Trouble with Girls (1969), accompanied by a troublesome girl, on piano, plus a vocal quartet of college boys. This is kinda sorta "Aura Lea" meets West Point graduation:

Violet, Violet

Flower of NYU

We will ever sing thy praise

To thee we'll e'er be true.

Elvis Presley was always perfectly at home with those "thees" and "thous": He would have made a fine record of "Aura Lea".

There was one problem with the film Love Me Tender. In test screenings, his fans didn't like the way Elvis (spoiler alert) dies. Wanting to stay true to the story while not offending millions of teenagers, the producers came up with a compromise. As his widow and brothers walk away from the funeral and return to the homestead, an ethereal Elvis would shimmer over the graveyard and sing a final round of "Love Me Tender" accompanying himself on a celestial guitar St Peter had lying around at the bottom of a pile of harps. So the hit songwriting team of "Vera Matson & Elvis Presley" were pressed into service one last time, and Ken Darby rattled off:

When at last my dreams come true

Darling, this I know

Happiness will follow you

Everywhere you goLove Me Tender, love me true

All my dreams fulfill

For you know that I love you

And I always will.

In other words: Go with my blessing, and fulfill all my dreams without me. There wasn't a dry eye in the house.

Elvis was a generous man. Singing "Love Me Tender" on stage over the years, he was wont to credit the number to Stephen Foster - either because he'd entirely forgotten he'd "written" it himself, or because he couldn't remember the guys he'd stolen it from, whether Poulton and Fosdick, or Ken Darby. But Foster didn't write it any more than Elvis did, so he might just as easily have credited it to Bach or Rimsky Korsakov.

As to why Ken Darby gave his missus, Vera Matson, the credit as Elvis' co-author on "Love Me Tender", Darby had a standard response:

Because she didn't write it either.

~If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, feel free to weigh in in our comments section over the competing merits of "Aura Lea", "Army Blue", "Love Me Tender" and "Violet (Flower of NYU)". As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so have at it. You also get personally autographed copies of A Song for the Season and many other Steyn books at a special member's price. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, see here - and check the first edition of our new Club newsletter, The Clubbable Steyn, for a seasonal song feature by Mark.