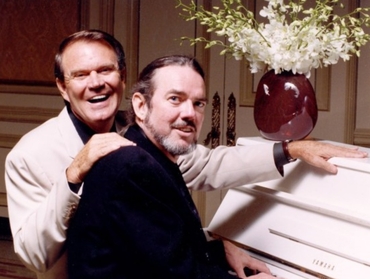

Glen Campbell died last Tuesday at the age of 81, and I blush to realize that his only appearance in these columns to date has been a parenthetic reference in our Sinatra Song of the Century #77:

"Strangers In The Night" had a huge impact on the guy playing that "chinking rhythm guitar", too. He was a fellow called Glen Campbell. At the time, he was a session guitarist with no particular interest in singing. "I'd never really paid that much attention to it, because I'm really a musician at heart. Singin' was, like, secondary," he said. "But when I heard the way he phrases, I said, 'Wow, that's really cool.'" Playing the melody along with Sinatra, he started to notice the way the singer pushed certain words and held back on others. He was so fascinated by the vocal technique he couldn't take his eyes off Frank. At the end of the session, Sinatra said to Jimmy Bowen, "Who's the faggot on guitar?"

A couple of years on, and Frank didn't need to ask that question. The guy making eyes at him had become a bona fide pop star getting the first hit on songs Sinatra found himself frantically playing catch-up on. Glen Campbell had smash bestsellers all the way through the end of the Seventies, and I certainly love those crossover pop-country Number Ones - "Rhinestone Cowboy", "Southern Nights" - for all the usual reasons, the girls and good times they evoke. But, when I think of Campbell at his best, I go back to a cluster of early hits, and one of them in particular. It was the centerpiece in a trilogy of "place" songs that began with "By The Time I Get to Phoenix" and ended with "Galveston". In between came:

I am a lineman for the county

And I drive the main road

Searchin' in the sun for another overload...

On Wednesday, hosting "The Fox News Specialists" with Eboni K Williams and Kat Timpf, I picked a little bit of "Wichita Lineman" to close out the show, and I said I remember when I first heard it and realized the trick of it - that a love song didn't always have to be about moon and June and stars above; sometimes it could be about a guy who works for the electric company up a pole on a deserted country road, and yet still be a love song. And later that night, as I was strolling down Sixth Avenue, two New Yorkers stopped me and said they liked that bit, and that I should expand on the thesis in our "Song of the Week" department. So here we go, off to Wichita...

When I heard the song as a kid, I'd never been to Wichita, or heard of it. As I wrote only last week, "To any foreigner who grew up hearing "Chattanooga Choo-Choo" and "I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo", American towns are the most musical on the planet." And, if my fancy was tickled sufficiently, I'd get out an atlas and look them up. Which I did with this strange song of the county lineman. There are two Wichita Counties - one in Kansas, one in Texas. So which one is this? Answer: Neither. Try the state in between:

I had just been back to visit my family, and I had been up in the flat country along the panhandle in Oklahoma, drivin' along, and I had seen these telephone poles along the road. It was kind of a surreal vista and hypnotic, and if you're not careful, you can, like my dad says, go to sleep and run off in the bar ditch. I was drivin' along there, just blinkin' and tryin' to stay awake, and all of a sudden there was somebody on top of one of those telephone poles—out of thousands of telephone poles, there's one that has a guy on it, and he had one of those little telephones hooked into the wires. I could see him on top of this pole talkin' or listenin' or doin' somethin' with this telephone. For some reason, the starkness of the image stayed with me like photography. I had never forgotten it.

That's the man who wrote "Wichita Lineman": Jimmy Webb. In all the years we've been running this series, we've never gotten around to a Jimmy Webb song, and I always figured that, when we did, it would be "Up, Up and Away", which is such a buoyant piece of pure pop, or "Didn't We?", an intense and intimate ballad that Sinatra loved, or even "MacArthur Park", whose reliable presence on all those Worst Songs of All Time lists only testifies to how loved it is, even the disco version. (Mr Webb's most recent book, by the way, is called The Cake and the Rain, and is a great and revealing read.) Webb was born in 1946 in Elk City, Oklahoma and raised in Wichita Falls, Texas, where his dad was enrolled in J Frank Norris' Bible Baptist Seminary. That's a very different kind of upbringing from a lot of the songwriters we feature here. Recently, for Sydney's Neighbourhood paper, Roger Norris asked Webb "if the sense of space in his songs comes from growing up in Oklahoma and Texas". The songwriter agreed:

I'm almost claustrophobic. I start feeling hemmed in very quickly. To me, the ocean strikes the same chord in my mind as the high plains of Oklahoma, which are basically flat. The old timers up there say 'You stand up on this little hill right here. You can see for fifty miles over into New Mexico.' Well, it's probably true. You can see a hell of a long way out there.

That feeling of boundlessness, I get chills a little bit thinking about it.

Webb didn't hear a lot of pop music growing up, because his father was a Baptist minister and didn't approve of it. As it happens, the very first record he bought as an adolescent was Glen Campbell's first ever hit record, "Turn Around, Look at Me" - and his ambition thereafter was one day to write a song that Glen Campbell would record. The family was now living in California, where young Jimmy was studying music. Then his mother died, and dad decided to move the family back to Oklahoma. The teenage Jimmy wanted to stay, and try to make it as a songwriter in Los Angeles. His father declared that this music bug was going to "break your heart", but gave him 40 bucks and wished him well. Still in his teens, he landed a song on the Supremes' Christmas album. "Up, Up and Away" and "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" followed shortly after.

The first records on "Phoenix" were by Johnny Rivers and Tony Martin. The big balladeer of "Stranger in Paradise" and "Kiss of Fire", Tony Martin had been signed to Motown Records because Berry Gordy didn't want his company to be just a black soul label, and hiring a white standards singer married to Cyd Charisse was the easiest way to demonstrate that. There's nothing wrong with Tony Martin's "Phoenix", but it wasn't until Glen Campbell recorded it that the song took off. After which everybody did it.

In October 1968, Campbell called Jimmy Webb and said he'd really appreciate another song that was like "Phoenix" - "something about a town". With the cockiness of youth, Jimmy told Glen that the Rand McNally phase of his career was over. Campbell persevered: Okay, if not a town, how about "something geographical"?

It was the first time Webb had been asked to write a song to order, for a particular performer - and in this case his very favorite performer. As usual, they wanted it that day, so Webb pottered around:

I had been driving around northern Oklahoma, an area that's real flat and remote – almost surreal in its boundless horizons and infinite distances. I'd seen a lineman up on a telephone pole, talking on the phone. It was such a curiosity to see a human being perched up there.

Imagine trying to pitch that to a publisher or producer: "It's a song about this guy who works for the utilities company..." But Webb meant it:

I am a lineman for the county

And I drive the main road

Searchin' in the sun for another overload...

He saw the poetry in the isolation:

This exquisite aesthetic balance of all these telephone poles just decreasing in size as they got further and further away from the viewer - that being me - and as I passed him, he began to diminish in size. The country is so flat, it was like this one quick snapshot of this guy rigged up on a pole with this telephone in his hand. And this song came about, really, from wondering what that was like, what it would be like to be working up on a telephone pole and what would you be talking about? Was he talking to his girlfriend? Probably just doing one of those checks where they called up and said, 'Mile marker 46,' you know. 'Everything's working so far.'

But nobody needs a song about "Mile marker 46". Whether or not the lineman was thinking about his girlfriend, Jimmy Webb certainly was: Her name was Susan Horton, the homecoming queen at Colton High School. But she married a schoolteacher called John, and Jimmy wrote "Wichita Lineman", "Up, Up and Away", "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" and even "MacArthur Park" all about his lost love in hopes of staunching the wound.

At the time Webb was living in the former Philippines consulate, just above Hollywood and La Brea, in Los Angeles. This being California in the Sixties, he was digging the communal vibe and had thirty or so housemates coming and going. The night before, as yet another jolly jape during the endless party, the communards had decided to turn Webb's baby grand a most un-piano-like color. So he found himself having to compose a new song for Glen Campbell on a green piano whose paint was still wet. To the old question "Which comes first - the words or the music?", the answer in this case seems to be: A fresh lick of paint. If that's what it takes, more writers should try it. Structurally, the tune divides into two halves: a seven-bar A theme to which Webb sets an almost prosaic statement of what the man does - his job, the route, all business - followed by an eight-bar B theme in which the guy gets a little more poetic and fanciful:

I hear you singin' in the wire

I can hear you through the whine...

The lyrical division is underlined by the music: The first section, beginning with that downbeat and bald declaration that "I am a lineman for the county", is written in F major, but the second, romantic section is in D. And the title phrase - "And the Wichita Lineman is still on the line" - never resolves, never gets safely home to the tonic, as if the guy's just left hanging there, on the line, as the shrinking poles vanish into the far horizon. "Somewhere in space I hang suspended," as they say in "Stranger in Paradise".

The second verse follows the same pattern. He's overworked but he has a job to do:

I know I need a small vacation

But it don't look like rain

And if it snows that stretch down south won't ever stand the strain...

And then his thoughts turn elsewhere:

And I need you more than want you

And I want you for all time...

As far as I'm aware, this is the first song about a guy who works for the utilities company since the pre-electric era. There's "The Lamplighter's Serenade" (by Hoagy Carmichael and Paul Francis Webster), which Jimmy Webb's pal Frank Sinatra recorded in 1942 at his very first session as a solo singer, and "The Old Lamplighter" (by Charles Tobias and Nat Simon), which was a big hit for Sammy Kaye a couple of years later. And they're both kinda sorta romantic in that, if there are couples courting in the park, the dear old gentleman sportingly leaves the adjacent lamppost unlit. And that's charming, but it's not full-strength, searing, aching love on the line like "Wichita Lineman". If you've read my book A Song for the Season, you might recall this passage with regard to George and Ira Gershwin's song "They All Laughed" ...at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round, Fulton and his steamboat, Hershey and his choc'late bar, etc:

The playwright George S Kaufman was out in Hollywood while the Gershwins were working on Shall We Dance?, and round the piano one day the brothers chose to give him a sneak preview. Kaufman sat there through Christopher Columbus, Edison recording sound, Wilbur and his brother being scorned for suggesting man could fly, but, after the lines 'They told Marconi/Wireless was a phony', he interrupted and said, 'Don't tell me this is going to be a love song!' He was somewhat antipathetic to the genre. Assuring him that it was, indeed, a profession of amorous affection, the brothers pressed on, and got to the release:

'They laughed at me wanting you'

– at which point Kaufman (as Ira described it) 'shook his head resignedly' and sighed, 'Oh, well.'

Jimmy Webb manages the transition far more economically - three lines of job talk ("that stretch down south won't ever stand the strain"), and then:

And I need you more than want you...

And the modulation makes it seem the most natural transition in the world. He continues:

And I want you for all time

And the Wichita Lineman is still on the line...

In his fine book on songwriting, Tunesmith, Jimmy Webb writes:

It is dreadful the way the same mistakes are perpetuated over and over again in songwriting, particularly the same careless false rhymes (identities) - 'time' with 'mine,' for example, 'self' with 'else,' 'girl' with 'world...

Wait a minute, 'time' with 'mine'? What about "want you for all time" with "still on the line"? Longtime readers will know I loathe impure rhymes, but I can sometimes, reluctantly, live with them buried in a verse or peripheral couplet or separated out in a quatrain. But this one ("time"/"line") comes right at the climax, and is an undeniable blemish on one of the most original songs ever written. As Webb sees it:

The false rhyme is with us so much on a daily basis that we simply don't hear it anymore (I didn't notice this mistake in 'Wichita Lineman' until years later). Is the distinction important? Well, yes and no. In popular music it comes down to a stubborn personal integrity: Do I want my lyrics to rhyme like bona fide poetry? And then this: If it comes down to a decision between using a false rhyme or losing the message in this song what will I do? Unfortunately in the latter case often the false rhyme is an excuse. To be idealistic the function of the lyricist is to change prose (or prose-based concepts) into authentically rhymed, emotionally affecting verse. False rhyme is to be frowned upon, especially when you've decided you're going to do it anyway.

Which I think is his way of saying he wouldn't write it that way today. But he was twenty years old, and it was a monster hit. So he's in the same position Tim Rice talked about in a recent video edition of our Song of the Week with regard to a neophyte's false rhymes in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat: Over the years, Tim's considered going back and cleaning up "beginning" and "dimming" , but fans won't hear of it. The world fell in love with the song as written, and they don't want a syllable changed, even by the author, no matter how much older and wiser he may be. Long ago on TV, I once had the honor of being asked to sing this song, and had no real idea of what I would do when I got to the false rhyme, but, when I did, it stuck in my throat and I found myself going back to the first verse:

And I need you more than want you

I can hear you through the whine

And the Wichita Lineman is still on the line

- which isn't the way anyone would write it, but I've always loved that "I hear you singin' in the wire/I can hear you through the whine" passage. Even though it's mostly one note save for the descent at the very end, it's so plaintive and evocative; and if you've ever heard or seen the sonic hum between two telegraph poles when the wind blows, you'll know what a great image of desolation it is - of human connection, and of the man it's bypassing. It's also a very American image - in the sense that in almost every other developed nation the electric lines are buried. Years ago, the novelist Sebastian Faulks came to stay with me because he was writing a book partly set in my neck of northern New England, A Fool's Alphabet (as I always say, when asked if I'm a character in the plot, he turned me into a woman and had sex with me. Don't you hate it when that happens?). Somewhere in there, his protagonist remarks that the landscape seems to need those above-ground poles, an observation which has some truth to it: "Telegraph cables sing down the highway," as "Moonlight in Vermont" has it. That said, I don't think a Vermont or New Hampshire county would be the same. You need the plain, and you need the name. Knowing it was inspired on a drive through Oklahoma, there are those who like to assert that the main road is Route 152 in Washita County. But the Washita Lineman is a poor substitute: You need the "tch" of Wichita; that's what makes it sing.

Still, Jimmy Webb felt it wasn't quite there. "They kept calling me back every couple of hours and asking if it was finished": The "Wichita Lineman" producers are still on the line - and desperate for their song. At four o'clock, he told Al De Lory it needed a third verse, but he'd send it over anyway and, if they liked it, he'd have another go at wrapping it up. Then he bought a can of turpentine and spent the rest of the day getting the green paint off the piano.

He'd kind of forgotten about the number when Glen Campbell showed up at his pad a week later bearing an acetate of "Wichita Lineman". "But it isn't finished," said Jimmy.

"It is now," said Glen, and played it. One of the qualities Webb admired about Campbell was his sense of what a song required - in production, arrangement, orchestration: He knew exactly how much was needed - and no more. "Wichita Lineman" is a brilliant testament to that, right from the opening bass line by Carol Kaye and building to the staccato strings and piano tapping out Morse Code-like the hum in the wire. The SOS subtly underlines why the song doesn't resolve musically - because, underneath all the stuff about his job, it's a cry for help: the poor lineman is what's really overloaded.

As for the third verse, Glen supplied that himself, simply taking his guitar down and playing the melody line of those first seven bars straight in what Webb calls a "slack key", Duane Eddy-style. You don't need anything else. A few lines sketch the job, a few more lines hint at lost love that will never come again, and all the rest is in the guitars and the strings and, above all, the pain in Glen Campbell's voice. It's an unimproveable record.

As I said, in theory it should have been a tough sell: "I've got this song about an employee of the electric company..." Yet, unbeknown to Webb, Al De Lory's uncle was an actual lineman for the county, in California, in Kern County. "As soon as I heard that opening line," De Lory recalled, "I could visualize my uncle up a pole in the middle of nowhere." What do they think about, those guys up on those poles? Love? Dinner? Hunting season? "I wanted it to be about an ordinary fellow," said Jimmy Webb. "Billy Joel came pretty close one time when he said 'Wichita Lineman' is 'a simple song about an ordinary man thinking extraordinary thoughts.' That got to me; it actually brought tears to my eyes. I had never really told anybody how close to the truth that was.

"What I was really trying to say was, you can see someone working in construction or working in a field, a migrant worker or a truck driver, and you may think you know what's going on inside him, but you don't... You can't assume that a man isn't a poet. And that's really what the song is about."

Jimmy Webb was a good friend to Glen Campbell through his final years and the long dark descent into the oblivion of Alzheimer's. Somewhere along the way, he said that just about the last coherent phrases Glen could articulate were song lyrics. "They'll remember a song after everything else is gone. They'll remember the lyrics. They'll remember the melody. They'll be staring out the window blankly. Then they'll burst into song." That was true in my dad's case, too. I remember going to see him in hospital when he could no longer string a sentence together, but something a nurse said prompted him to deliver "(Kiss me once, then kiss me twice, then kiss me once again) It's Been A Long, Long Time", all 32 bars, word-perfect. I was touched by Webb's reminiscence of his friend, and the muscle-memory that could still conjure up the gifts each man had given the other - great songs rewarded by great interpretations. And, even in the cloud of dementia, somewhere stretching through like telegraph poles on a county road is a line of pure poetry shining to the infinite horizon:

I hear you singin' in the wire

I can hear you through the whine...

Rest in peace.

~If you're a Mark Steyn Club member from Wichita, Phoenix, Galveston or beyond, feel free to weigh in in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so have at it. You also get personally autographed copies of A Song for the Season and many other Steyn books at a special member's price. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, see here - and check your mailbox for the first edition of our new Club newsletter, The Clubbable Steyn, complete with a seasonal song feature by Mark.