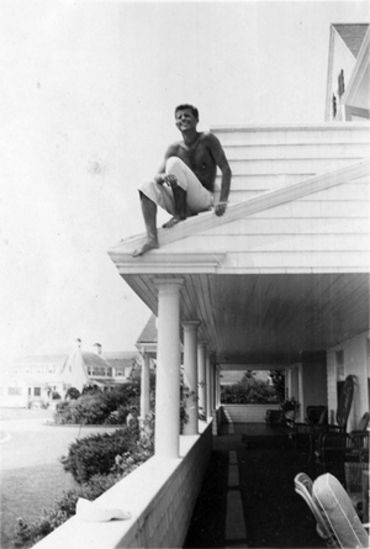

We mark the centenary of John F Kennedy's birth at SteynOnline with a song central to his widow's instant mythologizing of her slain husband. But that focuses on the end of his short life, and I felt, on his hundredth birthday, I ought to say something about the pre-mythological Jack, the Kennedy of those formative years.

I've met a handful of Kennedys in the course of my life, including, briefly, JFK Jr, and in no instance have I ever felt the slightest desire to prolong the acquaintance. All gave off a more than faintly obnoxious sense of entitlement, unredeemed - as it was by, say, Jack's in-laws, the Devonshires - by any sense of noblesse oblige. I wonder if I would have felt differently had I met young JFK during his progress from Brookline to Choate to the US Embassy in London and then to PT109 out in the Pacific. His favorite book is also one of mine, John Buchan's wonderfully evocative and illuminating memoir Memory Hold-the-Door. A bit of posthumous non-fiction by a Scots novelist, colonial servant and Canadian Governor General doesn't seem a book you'd choose unless you meant it - not like Al Gore claiming his all-time favorite tome is Stendhal's Le Rouge et Le Noir. Yeah, right. All those ghastly Camelot courtiers got to know Buchan, too, because he was forever quoting it to them, so they wound up reading it just so they could suck up by quoting it back at him. It's a good book for a man in young Jack's position: Buchan assumes that with the privilege of a comfortable upbringing and good education comes duty.

Jack's early life was certainly privileged but not idyllic. The family patriarch, Joe, is an easy target: an enthusiastic adulterer at home, and abroad, as US Ambassador to the Court of St James's, an equally enthusiastic appeaser. His wife, Rose, reacted to his infidelities by retreating into her social life. The distance she put between her and her husband also left her nine children (four of whom she would outlive) beached on the other side of the divide. She regarded them, as one biographer put it, as "a management exercise", and she believed in mostly hands-off management. Jack was a sickly child who spent months in hospital, but his mother was too far away to visit. Maternal affection was confined to a postcard from Paris, a ship-to-shore telegram from the Queen Mary. For the rest of his life, Kennedy disliked being touched or hugged even in the course of his many fleeting, transient sexual encounters.

Sex was fine. Anything more he found awkward and difficult. He showered up to five times a day. You can do your own analysis; everybody else does. "If he were my son," declared a master at Choate, "I should take him to a gland specialist." "He has never eaten enough vegetables," decided Rose.

Duty is more easily borne when the the world's eminences are your dinner companions. You meet the seigneurs, and you get to enjoy a little of their droit de, too. A former lover of Prince George, Duke of Kent introduced herself to young Jack as "a member of the British Royal Family by injection". The line seemed fresh to him, as it might not have a quarter-century later were random showgirls and mob molls running around Vegas and Malibu introducing themselves as members of the Kennedy family by injection. He signed his letters from Harvard, "Stout-hearted Kennedy, despoiler of women."

On the other hand, not many 24-year-olds get to shoot the breeze with Lord Halifax, British Ambassador in Washington, at the height of the Second World War about where the man he served as prime minister had gone wrong. "Halifax believed," wrote young Kennedy after their conversation, "that Chamberlain was misled and defeated by his phrases, which he did not really believe in, such as 'Peace in our time'." By the time Kennedy got into the phrase-making business, he left it to the professionals to craft all that sing-songy seesawing jingles people seem to think meets the definition of powerful rhetoric: Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country. Mankind must put an end to war or war will put an end to mankind. Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate. Mankind must put an end to cheap applause lines, but let us never fear to invert them formulaically yet portentously.

The JFK before the speechwriters got to him is far more interesting. "We are at a great disadvantage," Kennedy the gunboat skipper writes from the Pacific. "The Russians could see their country invaded, the Chinese the same. The British were bombed, but we are fighting on some islands belonging to the Lever Company, a British concern making soap... I suppose if we were stockholders we would perhaps be doing better, but to see that by dying at Munda you are helping to ensure peace in our time takes a larger imagination than most men possess."

He was a genuinely courageous man out there on the soapy shores of the Lever branch office, either because of that "larger imagination" he very much did possess, or because of the same reckless abandon he brought to his sex life, or maybe both. The dominant political question for the twentysomething Kennedy was how, in the light of British appeasement and American isolationism, a democracy could persuade its citizens of their wider responsibilities and long-term interests. Despite coming from a clan of professional Irishmen, he was unpersuaded by the shamrock-hued charms of Irish neutrality, As he declared in one of his first speeches, to an American Legion meeting, "A great many people in Eire feel that the only way to end partition is to come to an agreement with the British, to take a full part in the British Commonwealth of Nations, and to make a treaty of mutual defense. They argue that the British will not tolerate a sullen neutral on their vulnerable western flank." Hmm. I'd be interested to know what he meant by "a great many people in Eire". Seven? Twelve?

Conversely, his own country's domestic politics bored him. A Democrat for no other reason than that he was born into the party, he had no taste for the gladhanding and backslapping that American electioneering requires. His father was the natural at all that, and, understanding his son's reluctance, nevertheless demanded that the boy who couldn't bear to be touched and showered compulsively force himself to go around kissing babies and hugging malodorous working stiffs. Jack had never bothered to vote in a Democrat primary until his own in 1946. Dad was unimpressed. "With the money I spent", Joe Kennedy sneered afterwards, "I could have elected my chauffeur."

Most of what I know about young Jack comes from Nigel Hamilton's magisterial biography of the early years, Reckless Youth - "reckless" being a euphemism for "sex-fiend". I had forgotten the difficulty Hamilton had in connecting the sex with the geopolitics, but he gives it his best shot:

As Jack wooed his ladies, the European cauldron was meanwhile coming to a boil...

Did the earth boil for you too? And again:

Just as there was no political issue apart from the multi-party diversity of democracy in which Jack deeply believed, so his love life demonstrated no other principle than multi-woman diversity.

I'll bet Jack would have sent that line back to Ted Sorensen for a bit of a polish. A life doesn't have to make sense, doesn't have to connect the way the book of the life does. Kennedy was a literate, thoughtful man who liked to read Lord David Cecil and discuss learnedly whether Halifax could have served as Prime Minister from the House of Lords ...and then he'd go out and screw Mexican whores.

And maybe that would have been all his life had not war and the death of his older brother intervened. I mentioned in my piece on Camelot that I'd had the misfortune to sit through the tryout for JFK The Musical. The following day I was prevailed upon by the producers and by the Shuberts, who were interested in taking it to Broadway, to have lunch with the director and give him my two-bits. We sat in a booth at an IHOP, and I said, "You know what this show is? It's Gypsy in drag." He choked on his turkey, so I explained. At the end of Act One Jack's brother, Joe Jr, is killed in the war, and Joe Kennedy turns to the younger brother and says, "You're gonna be president!"

"Just like the Act One finale in Gypsy," I said. "Baby June runs off with one of the dancers, and Ethel Merman turns to the other sister and says, 'You're gonna be the star!' And then she sings, 'Everything's Coming Up Roses'. Now all you have to do is get those writers to come up with a Kennedyesque 'Everything's Coming Up Roses', which isn't the most obvious title for Joe Kennedy." The color drained from the director's cheeks. He pushed his plate aside, and said, "I hadn't thought of that. You're quite right. But you've just ruined the whole show for me." He meant that he'd never be able not to think of it as Gypsy in drag ever again.

And nor could I. Nigel Hamilton contents himself with analyzing the father/son relationship in more conventional terms: "Faustian bargain" and whatnot. Whatever. It was a surprise twist with no happy ending, but the family thought they could pull the switcheroo right down the line from Joe Jr to Jack to Bobby to Teddy and on to all those second- and third-generation indistinguishable Patrick Joseph Joseph Patrick Kennedy Shriver Lawford IVs, like an "Everything's Coming Up Roses" where no roses ever come up. The young Jack who read Cecil and Buchan would not recognize today's Democrat party, nor the political dispositions of most of his family.

~Don't forget that Founding Members of The Mark Steyn Club get to hit the comments section, so, if you disagree with Mark, feel free to log-in below and have at it. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, see here.