The Graduate is back on the big screen tomorrow, Sunday, in movie theaters across America in a special 50th anniversary presentation by Turner Classic Movies. If it's anywhere near your neck of the woods, don't miss it, if only for a sense of what a hit movie was in 1967. It was a film that, following Bonnie And Clyde, seemed to confirm that there was, indeed, a new cinematic aesthetic, a "New Hollywood". But, on the other hand, it was such a box-office smash it showed the studios that, if you got all the elements right, surfing the zeitgeist with Mrs Robinson could be as lucrative as warbling the Alps with Julie Andrews.

It started six years earlier, before the Sixties really got going, with a bona fide graduate. Charles Webb left Williams College in Massachusetts in 1961, went home to California, and started writing a novel about a recent graduate who goes home to California and embarks on an affair with the wife of his dad's business partner. The real-life model for Mrs Robinson was apparently a Mrs Erickson, although there was no affair. As for the author, the real Charles Webb is far too unreal ever to be in a movie. He married a lady by the name of Eve but calls her Fred out of solidarity for a support group for men with low self-esteem. They've been together for half-a-century but got divorced some years back to protest the institution of marriage. He received $20,000 for the movie rights plus a ten-grand bonus, which isn't a lot for a film that grossed $105 million - which, adjusted for inflation, comes to three-quarters of a billion. So to make ends meet he and Fred ran a nudist camp in New Jersey, and later worked at K-Mart. I believe they now live in Eastbourne, on the Sussex coast in England, which seems an awful long way from The Graduate.

Nevertheless, quite a lot of Charles Webb's novel survives in Mike Nichols' film, including most of the dialogue and almost all the most memorable set-pieces - Mrs Robinson's disrobing when Benjamin takes her home; the gift and subsequent public demonstration of the 21st-birthday scuba outfit; the visit to the strip club; etc. The Graduate was the first and best of Nichols' attempts to skewer — or at least package — a moment in the culture. And he put it together as expertly as Anna Wintour planning a dinner party: an eccentric and transgressive novel but given a conventional Hollywood comedy adaptation by Buck Henry and Calder Willingham but decked out with sorta kinda New Wavish directing tics by Nichols but hepped out by every suburban cul-de-sac's favorite MOR folk duo Simon & Garfunkel. It's all too cutely calculated for words, and Nichols's original choice for Mrs Robinson — Doris Day — would have made it cuter still. But Do-Do said no-no, objecting to the nudity, and they went with Anne Bancroft, whose Mrs R is real (and real sad) in a way that no one circling around her quite is.

The song helped. Years and years ago, at his home in Montauk, Paul Simon showed me his original draft sheets for the lyrics. He was late delivering the three new pieces he'd promised (Dave Grusin wrote the orchestral score) so he told Mike Nichols he'd had an idea for a song that was a remembrance of things past - about Joe DiMaggio and whatnot. "But I don't know if the song's called 'Mrs Roosevelt' or 'Mrs Robinson'," he said.

"We're making a movie here," snapped Nichols. "It's 'Mrs Robinson'."

The honorific is important. If she has a first name, it's never used. "Are you trying to seduce me, Mrs Robinson?" asks Benjamin, after bringing her purse upstairs to find her naked. Meeting a married woman for trysts under an assumed name in some hotel is grubby and sleazy. Yet The Graduate is the most conventional plot: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. It's just that the girl the boy wants to get is Elaine, the Robinsons' daughter. And he loses her when she finds out that he's been sleeping with her mother. Which is a not uncommon fantasy for young lads, but more problematic when it actually happens. Benjamin's reflexive lapse into formal address for his lover is the film's way of preserving the character's innocence. How can you not love a boy who's so polite he calls his mistress by her married name? Why, it's what Andy Hardy would do if he were bonking Polly Benedict's mom.

Their cleverest scene together is the one in which Benjamin asks Mrs Robinson if they can't, for once, talk about something. Conventionally, that would make him the "sensitive" one - the one who wants a meaningful relationship, rather than just uncomplicated rutting. But it comes across as cruel and heartless: He's too insensitive to sense her vulnerability, and too uncaring to try to figure it out. So, even in the New Hollywood, Benjamin is a traditionalist - opting for romance and conversation over sex and compartmentalization. Mike Nichols' genius was in finding the sweet spot where edgy sells, providing you smooth out all the rough stuff.

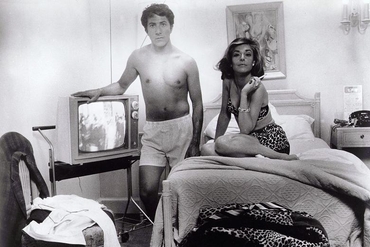

Young people were older back then: Benjamin, after all, has managed to graduate before his 21st birthday. Still, if you linger on him long enough, Dustin Hoffman looks closer to his age (30) than to his character's. Anne Bancroft's older woman was, in fact, less than six years older than Hoffman. Katharine Ross, playing her daughter, was a mere eight years younger than Miss Bancroft. You don't really notice any of this, because the performances are so perfectly poised. Hoffman was a self-conscious actor even then, and you wonder what a looser guy might have made of the part. But the deadpan expression that sees him through much of the film was a very shrewd call. He's good at conveying the lethargy of youth - all that lounging by the pool - which is not a quality inter-generational drama is much interested in. Likewise, Bancroft and Ross are differentiated not by the years but by their toll. Miss Ross is soft and unformed; Miss Bancroft has been hardened and hollowed by the stuff that formed her.

Nichols' directing style here is vaguely nouvelle with hints of Swingin' London: roaring turns in sporty motors, sodden visages pleading through rain-lashed windshields - and every so often Simon & Garfunkel with "The Sound of Silence" or "Scarborough Fair", an early example of the use of known pop records as dramatic underscore. But Nichols never forgets these things are there to accessorize the story, not distract from it - at least until the frenzied acceleration of his ever more neurotic characters into the final act.

Anne Bancroft was 73 when she died in 2005, far too young and still effortlessly sexy. You didn't see a lot of that in the old-lady cameos (GI Jane, Home for the Holidays) she settled into very prematurely, though perhaps understandably, having settled even more prematurely into predatory middle-age for The Graduate. There are strong opinions from all sides on her most famous performance, but I think it's very cannily judged: it's a beautiful trick to be able to be quite so wearily seductive, so erotically miserable, feline and peremptory, bored and desirable. I didn't fully appreciate it until the stage version of Webb's story fetched up in the West End with various women of a certain age stepping into Miss Bancroft's famous hosiery (Linda Gray from Dallas was the best). They could handle the sex but never grasped the bleak ennui. The Bancroft performance balances the cartoon characterizations surrounding her. It's a wonderful lesson in how to communicate through faraway looks and lethally timed delivery, how to conjure a whole life through the smallest of gestures, like the sour snap of a cigarette lighter.

Perhaps it's not surprising that nothing afterwards quite matched The Graduate, save for short turns as one half of an unlikely double-act with her husband Mel Brooks: they tango together deliciously in Silent Movie, and his Lubitsch remake To Be Or Not To Be gives us a Brooks & Bancroft duet so daffily irresistible the rest of the picture can't live up to it. They make an odd couple — a beautiful, somewhat regal woman with an insane imp prancing around her - but who else could pull off "Sweet Georgia Brown" sung in hot-jazz Polish? If Benjamin had asked Mrs Robinson for 16 bars of that in their hotel bedroom, it might all have turned out differently...