March saw, in rapid succession, Dame Vera Lynn's 100th birthday, a terrorist attack on Westminster Bridge and the Houses of Parliament, and Theresa May formally beginning the process of British withdrawal from the European Union. The combination of events put me in mind of this song. The essay below contains passages from my book A Song For The Season:

St George's Day, and Shakespeare's birthday, and England's national day falls later this month, April 23rd. The observances will be somewhat muted. Abroad, "England" is used somewhat carelessly by foreigners as a synonym for "Britain", "the United Kingdom" or "the British Isles", much to the irritation of the Scots, Irish and Welsh. But in Britain itself the word is curiously controversial, representing as it does a land all but banished from the official cartography of the state: The BBC has a "Radio Scotland", "Radio Ulster" and "Radio Wales", but no Radio England. Tony Blair endowed Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast with miniature parliaments but refused any such body for England, offering only vague proposals for regional assemblies in ersatz regions that live only in the bureaucratic imagination. The metropolitan powers are said to live in dread at loosing some unlovely form of English nationalism whose followers will quickly conclude that if anybody needs to secede from the United Kingdom it's not the Celts living it up on parliamentary overrepresentation and welfare benefits but the beleaguered English themselves.

Ah, well. Enough of that. This is our musical department, and I'm very fond of those English pop songs cranked out by music publishers in Denmark Street, London's Tin Pan Alley, between the wars. (After this weekend's Ottawa show, Tal Bachman and I repaired to a local hostelry, where at one point in the evening he reminisced about his own pilgrimage to Denmark Street a few years ago.) A surprising number made the big time in America: Ray Noble's "The Very Thought Of You", Campbell & Connelly's "Try A Little Tenderness", and "These Foolish Things" by Jack Strachey, Harry Link and a moonlighting BBC producer, Eric Maschwitz. Compared to their New York contemporaries, a lot of the Denmark Street chappies can sound a little archaic. But over the years I've come to love fellows like Carroll Coates, whose "Garden In The Rain" actually begins with "'Twas just a garden in the rain..." It's a quintessentially English romance, right down to the line "a touch of color 'neath skies of grey": The Sinatra recording has an especially fine Robert Farnon arrangement with a beautiful guitar coda.

But numbers that celebrate England more explicitly? They're harder to come by. Like many foreigners, I learned the American landscape through songs – "Moonlight In Vermont", "Old Kentucky Home", "Yellow Rose Of Texas", "Alabammy Bound"... English songwriters are more sheepish about place, and certainly more sheepish about home as an idea and an inspiration.

But there is a striking exception:

I give you a toast, ladies and gentlemen

I give you a toast, ladies and gentlemen

May this fair dear land we love so well

In dignity and freedom dwell...

Don't recognize it? Well, the verse is largely forgotten - although it's one of two big English hits to use the word "awry", the other being Noel Coward's "I'll See You Again" : "Though my world may go awry". It's a lovely word, especially set to Coward's notes. This second deployment of the thought is more pedestrian but it gets us nicely into the chorus:

Though worlds may change and go awry

While there is still one voice to cryThere'll Always Be An England...

Ah, yes: a song that's such a full-throated expression of love for England that it seems in some sense paradoxically unEnglish. And, in a way, that's not surprising. It was April 1939, a very dark spring in Europe, and one concentrating the minds of the London lyricist Ross Parker and his publisher. "He said, 'Ross, there's a song doing very well in the States called "God Bless America". Think you can do one like it?' So I sat down and wrote, 'There'll Always Be An England'."

In 1939, England didn't seem so quite so obviously blessed by the Almighty as America, but Parker and his composing partner Hughie Charles set to it. It's a stirring declarative martial song but with, at least initially, oddly delicate imagery:

There'll Always Be An England

While there's a country lane

Wherever there's a cottage small

Beside a field of grain...

Six years later, at the end of the war, Ivor Novello was writing:

We'll Gather Lilacs in the spring again

And walk together down an English lane...

Even in a small and highly urbanized state, the idea of a rural England is very potent. I once had a long and rather moving conversation with Mrs Thatcher, as we stood side by side looking through the mullioned windows of an ancient manor house at the lawns and fields beyond, about how England had more or less invented the idea of the "countryside". Not the semi-wilderness of the Great North Woods in Maine and New Hampshire, but a very ordered, very English kind of country - a patchwork of lanes and hedgerows and stiles centered around a church and a pub and a manor house. Even in the cities, the myth of a bucolic rural England is a potent one. So, having doffed his Denmark Street cap to it, Ross Parker moves on to the great industrial cities:

There'll Always Be An England

While there's a busy street

Wherever there's a turning wheel

A million marching feet...

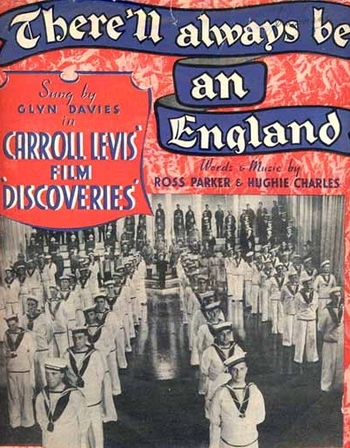

That's more like it. Billy Cotton and his band introduced the song at the Elephant and Castle, and it went down so well it was decided it was just the ticket for a film called Discoveries, starring Doris Hare and Issy Bonn and a bunch of variety acts, and loosely inspired by a BBC talent-spotting show. It was August, the eve of war, and the picture had already been previewed, but the producers figured the public was hungering for a big patriotic finale. So they got in a ten-year old boy, Glynn Davies, to sing "There'll Always be an England" accompanied by full chorus, military band, thousands (well, dozens) of extras on a set festooned in Union Flags, and grafted it on to the end of the movie. It was the first war song of the new struggle, not just for England, but for His Majesty's realms beyond these islands:

Red, white and blue

What does it mean to you?

Surely you're proud

Shout it aloud

'Britons, awake!'The Empire too

We can depend on you.

Freedom remains

These are the chains

Nothing can break....

And so it seemed, as an unprepared British Empire found itself dragged into yet another European conflict. When the moment came for London and the Dominions to declare war on Germany, "There'll Always Be An England" was the Number One song in Canada and many other parts of the Empire. Dennis Noble and Vincent Tildsley's Mastersingers and a few other acts of the day had the first records on the song but it was a young female singer, soon to become Britain's Forces' Sweetheart, who embedded it in the heart of a nation. And when she got to the final eight bars, a contrived local knock-off of "God Bless America" was suddenly the real thing, genuine lump-in-the-throat stuff:

There'll Always Be An England

And England shall be free

If England means as much to you

As England means to me!

Hughie Charles was a genial old fellow in a battered trilby enjoying his retirement by the time I met him. But I asked him whether Ross Parker had written the words "And England shall be free" as a conscious evocation of "Britons never never never shall be slaves" from "Rule, Britannia", and he said he thought it was probably unconscious. If so, it was extremely fortuitous: A very foursquare song, it was nevertheless the one that summed up what was at stake in that testing time between the fall of France and Pearl Harbor when Britannia and her lion cubs stood alone. Its sentiment matched the challenge posed by Churchill: Does England mean as much to you as England means to me? If it does, we can press on, and win.

1939 set Hughie Charles and Ross Parker up very nicely for the next six years. They'd written their first hit the previous year, "I Won't Tell A Soul (That I Love You)", recorded by a handful of the top British dance bands - Roy Fox, Victor Sylvester, Lew Stone. Twelve months later, the blithe innocence of that song seemed to belong to a lost world. After "There'll Always Be An England", they decided to address the impending global apocalypse rather more obliquely:

We'll Meet Again

Don't know where, don't know when

But I know We'll Meet Again

Some sunny day...

Its slightly stodgy optimism is quintessentially British:

Keep smiling through

Just like you always do

Till the blue skies

Drive the dark clouds far away...

In that summer of '39, they passed it to the bandleader Ambrose, who'd taken on a young singer called Vera Lynn. She'd sung with the Charlie Kunz orchestra and had made a solo record of a leaden novelty called "Up The Wooden Hill To Bedfordshire". But Hughie Charles considered Vera "a very nice kid" and thought "We'll Meet Again" would be right for her. So Ambrose worked up an arrangement and, as Dame Vera told me a few years back, audiences responded to it immediately, and it quickly became her sign-off song - especially when she landed her own BBC radio show a few months into the war. "We'll Meet Again" made Vera Lynn a star. She's certainly known in America - in the Fifties, before the Beatles or the Rolling Stones or anybody else, "Auf Wiedersehen, Sweetheart" made her the first British pop star ever to have a Number One hit on the Billboard charts. But the scale of her wartime celebrity in Britain and much of the Commonwealth is of an entirely different order. She was born in East Ham, and began singing at the age of seven in the local working men's club. In Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, I recall a rather depressing lunch presided over by Princess Margaret, at which I sat next to Dame Vera and her husband (and former clarinetist) Harry. But I was rather touched to find that, despite her advance from Forces' Sweetheart to national icon, she still had a pronounced Cockney in her speaking voice.

Not when she sang, though. It's not a creamy voice, like GI Jo Stafford's. There's something rawer in there, and in those early records a very real emotional clutch. The sound of Britain at war is Vera Lynn singing, whether "There'll Always Be And England" or "We'll Meet Again". And, with either number, despite the notorious British antipathy to audience participation, she never had to cajole the Tommies or anybody else into joining in.

On that rather strained luncheon with Princess Margaret, Dame Vera seemed a delightfully near parodic embodiment of Englishness. (She sent back the avocado with the words, "This foreign food disagrees with me.") Afterwards, we had a little chat about her songs. "They still like 'We'll Meet Again'," she said (I seem to recall a couple of laddish telly pop stars had just had a Number One cover version with it). "But 'There'll Always Be An England' is what they call 'controversial'," she added, lowering her voice, lest someone might overhear.

By "controversial", she meant that the very concept of "England" was now officially discouraged. "There'll Always Be An England" is conspicuous by its absence on her 100th birthday album and her other hit CDs of this century. With one of her two signature songs all but banned from the airwaves, the survivor was imbued with a kind of pathos it had never had during the lowest moments of the Second World War. It came to symbolize simultaneously both Britain's wartime defiance and a resigned acceptance of remorseless decline. To me, Dame Vera's original near-eight-decade-old recording sounds sadder with every passing year:

We'll Meet Again

Don't know where, don't know when

But I know We'll Meet Again

Some sunny day.

Will we? You can see what Dame Vera means about the "controversial" nature of "There'll Always Be An England" at the Blairite website set up after the 2005 Tube bombings. Its object was to try to identify British "icons" around which a roiled nation could unite. In the comments responding to "There'll Always Be...", a reader who identifies himself as Alex rages that the song is "an appallingly syrupy anthem to petty nationalism and 'little Englanders'. Haven't two world wars shown us that nationalism is a scourge, a hangover from the tribal groupings of the Dark Ages? I'm a citizen of a united Europe, and proud to be so." On the other hand, Margaret Stringfellow says, "The EU is hell bent on destroying England as a country, by replacing England by the Regions. There will not always be an England unless the English people wake up."

Incidentally, that line of Alex is a classic example of how even Britons learn the wrong lessons from history - in this case that "two world wars" had exposed nationalism as "a scourge". As for "appallingly syrupy", evidently the country lane and field of grain no longer resonate, at least with him. In the early Nineties, to blunt the arguments advanced by the likes of Margaret Stringfellow, the Prime Minister John Major declared:

Fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and, as George Orwell said, 'Old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist' and, if we get our way, Shakespeare will still be read even in school.

I doubt it. Old maids bicycling between the Euro-juggernauts on the bypass were a rare sight even 15 years ago, and will be rarer still circa the early 2040s. And I wonder if we'll still be aware of "There'll Always Be An England". It's a curious entry in the song catalogue. The phrase is known and, credited to Parker and Charles, turns up in Bartlett's and any number of other collections of quotations. But it's not sung very often and when it is - at least since Tiny Tim did it at the Isle of Wight pop festival in 1970 – it's usually performed with heavy-handed irony.

Truly it belongs to a pre-ironic England. On November 25th 1941, off the coast of Alexandria, HMS Barham was torpedoed by a German U-boat during a visit to the battleship by Vice-Admiral Henry Pridham-Wippell. The ship lurched to its port side, the commanding officer was killed, and the vice-admiral found himself treading oil-perfumed water surrounded by the ship's men and far from rafts. To keep their morale up, he led them in a rendition of "There'll Always Be An England". The 31,000-ton Barham sank in less than four minutes, the largest British warship destroyed by a U-boat in the course of the war. But 449 of its crew of 1,311 survived.

"There'll Always Be An England" was written for that England.

It's different now. It's still a popular headline, but today there's a question mark at the end, either explicit or implied. And, if Dame Vera were to sing it now, that "if" in the penultimate line is more conditional than it's ever been:

There'll Always Be An England

And England shall be free

If England means as much to you

As England means to me.

~adapted from Mark's book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

~For a live musical performance of a wartime song written the same year as "There'll Always Be An England" - but from a different part of the Empire - see Tal Bachman's lovely version of "I'll Never Smile Again" on this weekend's edition of The Mark Steyn Show.