This week Bob Dylan became the first songwriter to win the Nobel Prize for Literature - to general acclamation. But not from me, and I'd feel the same way if they'd given it to Cole Porter or Oscar Hammerstein or W S Gilbert. Ira Gershwin liked to cite the old Encyclopedia Britannica definition:

SONG is the joint art of words and music, two arts under emotional pressure coalescing into a third.

Bob Dylan is a practitioner of that third art: not words, not music, but the transformation that occurs when the former sit upon the latter.

At any rate, here's what I had to say about the great man upon the occasion of his 60th birthday way back in May 2001. Re the Dean Martin reference below, note that Dylan's big new releases in recent years have been two albums of Sinatra songs - the very cleverly named Shadows In The Night and its successor Fallen Angels, both of which remind us that in late life Dylan seems to get more satisfaction out of being an interpretative artist. The piece below is anthologized in my book The [Un]documented Mark Steyn, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore - oh, and don't forget the audio version:

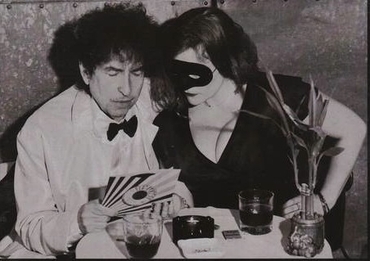

I first noticed a sudden uptick in Bob Dylan articles maybe a couple of months ago, when instead of Pamela Anderson's breasts or J-Lo's bottom bursting through the National Post masthead there appeared to be a shriveled penis that had spent way too long in the bath. On closer inspection, this turned out to be Bob Dylan's head. He was, it seems, getting ready to celebrate his birthday. For today he turns 60.

Sixty? I think the last time I saw him on TV was the 80th birthday tribute to Sinatra six years ago, and, to judge from their respective states, if Frank was 80, Bob had to be at least 130. He mumbled his way through "Restless Farewell", though neither words nor tune were discernible, and then shyly offered, "Happy Birthday, Mister Frank." Frank sat through the number with a stunned look, no doubt thinking, "Geez, that's what I could look like in another 20, 25 years if I don't ease up on the late nights."

Still, Bob's made it to 60, and for that we should be grateful. After all, for the grizzled old hippies, folkies and peaceniks who spent the Sixties bellowing along with "How does it feeeeeel?" these have been worrying times. A couple of years ago, Bob's management were canceling his tours and the only people demanding to know "How does it feeeeeel?" were Dylan's doctors, treating him in New York for histoplasmosis, a fungal infection that in rare cases can lead to potentially fatal swelling in the pericardial sac. If the first question on your lips is "How is histoplasmosis spread?" well, it's caused by fungal spores which invade the lungs through airborne bat droppings. In other words, the answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind.

He has, of course, looked famously unhealthy for years, even by the impressive standards of Sixties survivors. He was at the Vatican not so long ago and, although we do not know for certain what the Pope said as the leathery, wizened, stooped figure with gnarled hands and worn garb was ushered into the holy presence, it was probably something along the lines of, "Mother Teresa! But they told me you were dead!" "No, no, your Holiness," an aide would have hastily explained. "This is Bob Dylan, the voice of a disaffected generation."

It is not for me to join the vast army of Dylanologists who've been poring over his songs for 30 years. As Bob himself once said, "They are whatever they are to whoever's listening to them." End of story. But it does seem to me that, while most rock stars pursue eternal youth, Dylan has always sought premature geezerdom. The traditional elderly rocker look is best exemplified by Gram'pa Rod Stewart: peroxide hair with that toss-a-space-heater-in-the-bathtub look, tight gold lamé pants with extravagant codpiece, pneumatic supermodel on your arm. By contrast, Bob, barely out of his teens, consciously adopted an aged singing voice and the experience it implied, a quintessentially Dylanesque jest on pop's Peter Pan ethos.

When he emerged in the early Sixties, he was supposedly a drifter who had spent years on the backroads of America picking up folk songs from wrinkly old-timers, and who provoked Robert Shelton of The New York Times to rhapsodize about "the rude beauty of a Southern field hand musing in melody on his porch." Actually, he'd toiled instead at the University of Minnesota - a Jewish college boy, son of an appliance store manager. The folk songs he knew had been picked up not from any real live folk, but from the records of Ramblin' Jack Elliott. Ramblin' Jack had rambled over from Brooklyn, dropping his own Jewish name - Elliott Adnopoz - en route. "There was not another sonofabitch in the country that could sing until Bob Dylan came along," pronounced Ramblin' Jack, with a pithiness that belies his sobriquet. "Everybody else was singing like a damned faggot." It's one of the more modest claims made on Dylan's behalf.

His first album was composed almost entirely of traditional material. But by the second he was singing his own compositions, pioneering the musical oxymoron of the era, the "original folk song": No longer did a folk song have to be something of indeterminate origin sung by generations of inbred mountain men after a couple of jiggers of moonshine and a bunk-up with their sisters. Now a "folk song" could be "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" or "The Times They Are A- Changin'". I'm reminded of that episode of, appropriately enough, "The Golden Girls", when Estelle Getty comes rushing in shouting, "The hurricane's a-comin'! The hurricane's a-comin'!"

"Ma!" Bea Arthur scolds her. "A-comin'?"

With Dylan, the songwriting styles they were a-regressin', the slyly seductive archaisms and harmonica obbligato designed to evoke the integrity of American popular music before the Tin Pan Alley hucksters took over.

"Without Bob the Beatles wouldn't have made Sergeant Pepper, the Beach Boys wouldn't have made Pet Sounds," said Bruce Springsteen. "U2 wouldn't have done 'Pride in the Name of Love'," he continued, warming to his theme. "The Count Five would not have done 'Psychotic Reaction'. There never would have been a group named the Electric Prunes."

But why hold all that against him? If rock lyrics wound up as clogged and bloated as Dylan's pericardial sac, that's hardly his fault. Bob, for his part, has doggedly pursued his quest to turn back the clock. He's on the new Sopranos soundtrack CD, singing Dean Martin's "Return To Me", complete with chorus in Italian. Just the latest reinvention: Bob Dino, suburban crooner.

Visiting America a few years ago, Dave Stewart, of the Eurythmics, said to Dylan that the next time he was in England he should drop by his recording studio in Crouch End, an undistinguished north London suburb. Dylan, at a loose end one afternoon, decided to take him up on it and asked a taxi-driver to take him to Crouch End Hill. Cruising the bewildering array of near-namesake streets - Crouch End Hill, Crouch End Road, Crouch Hill End, Crouch Hill Road and various other permutations of "Crouch," "End" and "Hill" - the cabbie accidentally dropped him off at the right number but in an adjoining street of small row houses. Dylan knocked at the front door and asked the woman who answered if Dave was in.

"No," she said, assuming he was referring to her husband, Dave, who was out on a plumbing job. "But he should be back soon." Bob asked if she would mind if he waited. Twenty minutes later, Dave - the plumber, not the rock star - returned and asked the missus whether there were any messages. "No," she said, "but Bob Dylan's in the front room having a cup of tea."

It's a sweet image, compounded by the subsequent rumour that Dylan had been seen with local realtors looking for a house in the area. Perhaps deep inside his southern field-hand persona is a suburban sexagenarian pining for a quiet life in a residential cul de sac, dispensing advice over the fence to the next-door neighbour on how to keep your lawn free of grass clippings: "The answer, my friend, is mowin' in the wind."

Happy birthday, Mister Bob.

~The above is anthologized in Mark's recent book The [Un]documented Mark Steyn, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore - or pristinely unautographed in the audio edition, read by Mark.