Francis Crick, the man who gave us DNA, was born a century ago today - June 8th 1916, in Northamptonshire in the English Midlands. Here's what I had to say about him upon his death 12 years ago. This essay appears in Mark Steyn's Passing Parade:

Francis Crick is dead and gone. He has certainly not "passed on" - and, if he has, he'll be extremely annoyed about it. As a 12-year old English schoolboy, he decided he was an atheist, and for much of the rest of his life worked hard to disprove the existence of the soul.

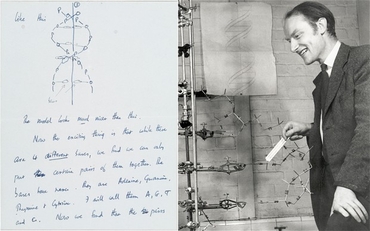

In between, he "discovered the secret of life", as he crowed to the barmaids and regulars at the Eagle, his Cambridge pub, on a triumphant night in 1953. The opening sentence of his paper, written with his colleague Jim Watson, for Nature on April 25th that year put it more modestly:

We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid.

That's DNA to you and me. And it's thanks to Crick and Watson that we know the acronym and that it's passed into the language as the contemporary shorthand for our core identity. Your career choice? "She says being a part of academia seemed to be hard-wired into her DNA because her father was a professor at the University of Virginia." (The Chicago Tribune) Socio-economic inequality? "Income distribution appears to be hard-wired into the DNA of a nation." (The Washington Post) New trends in rock video? "Staying cool is hard-wired into the DNA of MTV." (The Los Angeles Times)

Francis Crick was the most important biologist of the 20th century. Like Darwin, he changed the way we think of ourselves. First, with Watson, he came up with one of the few scientific blueprints known to the general public – the double-helix structure of DNA (though he left it to Mrs Crick, usually a painter of nudes, to create the model). Later, with Sydney Brenner, he unraveled the universal genetic code. Today, Crick's legacy includes all the thorniest questions of our time - genetic fingerprinting, stem-cell research, pre-screening for hereditary diseases, the "gay gene" and all the other "genes of the week"... In Britain, they're arguing about a national DNA database; on the Continent, anti-globalists are protesting genetically modified crops; in America, it was traces of, um, DNA on Monica's blue dress that obliged Bill Clinton to change his story. If you're really determined, you can still just about ignore DNA – the OJ jury did – but, increasingly, it's the currency of the age. Crick called his home in Cambridge the Golden Helix, and it truly was golden – not so much for him personally but for the biotechnology industry, something of a contradiction in terms half-a-century ago but now a 30-bil-a-year bonanza.

"We were lucky with DNA," he said. "Like America, it was just waiting to be discovered." But Crick was an unlikely Columbus. The son of a boot factory owner, he grew up in the English Midlands, dabbling in the usual scientific experiments of small boys – blowing up bottles, etc – but never really progressing beyond. Indeed, as a scientist, he wasn't one for conducting experiments. What he did was think, and even then it took him a while to think out what he ought to be thinking about. His studies were interrupted by the war, which he spent developing mines at the British Admiralty's research laboratory. Afterwards, already 30 and at a loose end, he mulled over what he wanted to do and decided his main interests were the "big picture" questions, the ones arising from his rejection of God, the ones that seemed beyond the power of science. Crick reckoned that the "mystery of life" could be easily understood if you just cleared away all the mysticism we've chosen to surround it with.

That's the difference between Darwin and Crick. Evolution, whatever offence it gives, by definition emphasizes how far man has come from his tree-swinging forebears. DNA, by contrast, seems reductive. Man and chimp share 98.5 per cent of their genetic code, which would be no surprise to Darwin. But we also share 75 per cent of our genetic make-up with the pumpkin. The pumpkin is just a big ridged orange lump lying on the ground all day, like a fat retiree on the beach in Florida. But other than that he has no discernible human characteristics until your kid carves them into him.

Yet the point of DNA is not just to prove that the pumpkin is our kin but to pump him for useful information. According to Monise Durrani, a BBC science correspondent, the genetic blueprint of the humble earthworm is proving useful in the study of Alzheimer's. Do worms get Alzheimer's? And, if they do, what difference does it make? As Ms Durrani says, "Although we like to think we are special, our genes bring us down to Earth... We all evolved from the same soup of chemicals." It turns out there is a fly in my soup, and a chimp and a worm and a pumpkin.

Having found "the secret of life", what do you do for an encore? Crick disliked celebrity, and had a standard reply card printed to fend off his fellow man: "Dr. Crick thanks you for your letter but regrets that he is unable to accept your kind invitation to..." There then followed a checklist of options with a tick by the relevant item: send an autograph, provide a photograph, appear on your radio or TV show, cure your disease, etc. This is a view of man as 75 per cent pumpkin but capable of crude, predictable, repetitive patterns of imposition on more advanced forms of life. Dr Crick also turned down automatically honorary degrees and disdained the feudal honors offered by the British state. Presumably the hyper-rationalist in him consigned monarchical mumbo-jumbo to the same trash can of history as religion, though he eventually relented and accepted an invitation by the Queen to join her most elite Order of Merit. Religion he never let up on. The university at which he practiced his science is filled with ancient college chapels, whose presence so irked Crick that, when the new Churchill College invited him to become a Fellow, he agreed to do so only on condition that no chapel was built on the grounds. In 1963, when a benefactor offered to fund a chapel and Crick's fellow Fellows voted to accept the money, he refused to accept the argument that many at the college would appreciate a place of worship and that those who didn't were not obliged to enter it. He offered to fund a brothel on the same basis, and, when that was rejected, he resigned.

His militant atheism was good-humored but fierce, and it drove him away from molecular biology. As the key to the mystery of life, DNA seems a small answer to the big picture, so Crick pushed on, advancing the theory of "Directed Panspermia", which is not a Clinton DNA joke but his and his colleague Leslie Orgel's explanation for how life began. Concerned by the narrow time frame – to those of a non-creationist bent - between the cooling of the earth and the rapid emergence of the planet's first life forms, Crick determined to provide another explanation for the origin of life. As he put it, bouncing along a tenuous chain of probabilities, "The first self-replicating system is believed to have arisen spontaneously in the 'soup,' the weak solution of organic chemicals formed in the oceans, seas, and lakes by the action of sunlight and electric storms. Exactly how it started we do not know...

The universe began much earlier. Its exact age is uncertain but a figure of 10 to 15 billion years is not too far out...

Although we do not know for certain, we suspect that there are in the galaxy many stars with planets suitable for life...

Could life have first started much earlier on the planet of some distant star, perhaps eight to 10 billion years ago? If so, a higher civilization, similar to ours, might have developed from it at about the time that the Earth was formed... Would they have had the urge and the technology to spread life through the wastes of space and seed these sterile planets, including our own?..

For such a job, bacteria are ideal. Since they are small, many of them can be sent. They can be stored almost indefinitely at very low temperatures, and the chances are they would multiply easily in the 'soup' of the primitive ocean...

"We do not know... uncertain... not too far out... we do not know for certain... we suspect... chances are..." And thus the Nobel prize winner embraces the theory that space aliens sent rocketships to seed the earth. The man of science who confidently dismissed God at Mill Hill School half a century earlier appears not to have noticed that he'd merely substituted for his culturally inherited monotheism a weary variant on Greco-Roman-Norse pantheism – the gods in the skies who fertilize the earth and then retreat to the heavens beyond our reach. To be sure, he leaves them as anonymous aliens showering seed rather than Zeus adopting the form of a swan, but nevertheless Dr Crick's hyper-rationalism took 50 years to lead him round to embracing a belief in a celestial creator of human life, indeed a deus ex machina.

He didn't see it that way, of course. His last major work, The Astonishing Hypothesis, was a full-scale assault on human feeling. "The Astonishing Hypothesis," trumpeted Crick, "is that 'You,' your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. As Lewis Carroll's Alice might have phrased it: 'You're nothing but a pack of neurons.'"

It's not a new idea. Round about the time Dr Crick was working on his double-helix, Cole Porter wrote a song for a surly Soviet lass fending off the attentions of an amorous American:

When the electromagnetic of the he-male

Meets the electromagnetic of the female

If right away she should say this is the male

It's A Chemical Reaction, That's All.

Of course, in the film of Silk Stockings, Cyd Charisse eventually succumbs to Fred Astaire and comes to understand her thesis is not the final word. Even if the Astonishing Hypothesis – that there's no "You", no thoughts, no feelings, no falling in love, no free will - is true, it's so all-encompassing as to be useless except to the most sinister eugenicists. And in the end Francis Crick's own life seems to disprove it: He was never a dry or pompous scientist, he liked jokes and costume parties, he was an undistinguished man pushing 40 with one great obsession. Perhaps the combination of human quirks and sparks that drove him to chase his double-helix are merely a chemical formula no different in principle from that which determines variations in the pumpkin patch. But, even if Francis Crick is 75 per cent the same as a pumpkin, the degree of difference between him and even the savviest Hubbard squash suggests that as a unit of measurement it doesn't quite suffice.

It is too late to retreat now. Francis Crick set us on the path to a biotechnological era that may yet be only an intermediate stage to a post-human future. But, just as a joke that's explained is no longer funny, so in his final astonishing hypothesis Dr Crick eventually arrived at the logical end: you can only unmask the mystery of humanity by denying our humanity.

~The above essay appears in the book Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, which is available in newly expanded eBook and can be yours within minutes from Amazon worldwide and other retailers, or in good old-fashioned personally autographed print version exclusively from the SteynOnline bookstore.