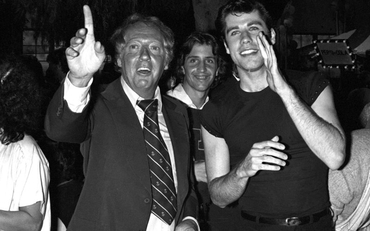

Robert Stigwood died a few days ago at the age of 81 and a long way from the celebrity he enjoyed at the height of his powers. Born in Port Pirie, South Australia, he came to London with three quid in his pocket, set up a talent agency, and a few years later had his first success with John Leyton's gravediggin' smash from an otherwise forgettable telly show, "Johnny, Remember Me". Over the next couple of decades he had a multi-media Midas touch: He put Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker together into a group called Cream. He discovered some Aussie siblings, the brothers Gibb, as in "Bee" "Gees". He founded a writers' agency and sold the formats of Brit TV staples like "Till Death Us Do Part" and "Steptoe & Son" to American networks, where they became, respectively, "All In The Family" and "Sanford & Son". He moved into theatre with Hair and Oh, Calcutta! and then got together with Tim Rice & Andrew Lloyd Webber for Evita. He optioned a magazine piece about disco, asked the Bee Gees to write a few songs, spotted a bloke in a sitcom called "Welcome Back, Kotter" he thought might be good for the lead, and turned it into Saturday Night Fever. Which is how a South Australian came to wind up almost singlehandedly owning what was left of the big screen musical in the late Seventies. The moment passed, as it almost always does, and aside from a hand in ventures such as Madonna's film version of Evita, he faded from the scene. Nevertheless, for our Saturday movie date, here's a Robert Stigwood production from 1978. With the "Kotter" bloke and his compatriot Olivia Newton-John, and a Hollywood chancer called Allan Carr, Stigwood took a so-so Broadway musical and made it iconic:

Grease is the word! What a cool line that was. I've always had a soft spot for the Frankie Valli title song: in my fledgling disc-jockey days, it had one of the best intros for talking over; but, when you stopped talking, the rest of the song was pretty good, too. I also have a wistful recollection from what seems like a thousand summers ago of heading up to Georgian Bay in Ontario one Friday afternoon with a pal in his Mustang with the top down and a couple of gal hitch-hikers in the back, as "Grease" came on the radio and all the weekend's possibilities shimmered invitingly on the hazy asphalt ahead. The possibilities didn't quite pan out, as is the way, but I can't hear Frankie Valli singing that thing without getting the old whiff of anticipation.

Alas, to the siren song of nostalgia, much of the actual movie of Grease is the equivalent of Dr van Helsing showing up with a couple of bushels of garlic and a large stake. The movie in my memory makes more of Frankie Valli than the title sequence here — just a dull set of animated titles which in tempo, rhythm or the crudest sense of pacing relates to the song not one whit. On the other hand, I was pleased to discover that not only is the intro to the record still great for talking all over but so too is most of the movie's dialogue.

Grease, according to the title song, is doubly blessed: "It's got groove, it's got meaning." In fact, it's got neither — the lack of groove being the rather more surprising defect. Instead, it has a kind of hokey charm that's almost impossible to resist. It thinks it's better - or at any rate more knowing - than old-school straight-up sock-hop movies, but its appeal rests almost entirely on a shambolic amateurishness that gives it a strange authenticity. We shouldn't waste much time blaming the director — one Randal Kleisner. Instead, the presiding geniuses were Stigwood and his partner Allan Carr, co-producer and screenplay "adapter". Carr is best known for concocting the most tasteless Oscars ceremony ever — the one where Snow White and Rob Lowe dueted on a special-material rewrite of Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary"— "Rolling, rolling, keep the cameras rolling" — accompanied by dancing nightclub tables and bulky waitresses wearing Carmen Miranda fruit arrangements. If only he'd been similarly inspired here.

Instead, Carr had enough savvy to figure out that the original Broadway show, by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey, was thin stuff: The story attends to no more than whether Danny and Sandy's summer romance can rekindle in the subsequent school year. As for the score, you can gauge its quality by the fact that the songs people remember from Grease — "You're The One That I Want", "Hopelessly Devoted To You" - are not by Jacobs and Casey but instead by other writers Stigwood and Carr called in for the movie version. Although they evidently knew a good tune when they heard one, Stigwood permitted Carr to stick to the overly literal staging that finally came such a cropper on that Oscar night. You'll grasp their appreciation of a song's potential to advance plot and illuminate character by one masterly deployment: they uses Rodgers & Hart's ""Blue Moon" to accompany a display of mooning. As I've renewed my acquaintance with this scene over the years, I've come to admire considerably the paradoxically inspired lack of inspiration.

Similarly, the film rounds up all kinds of beloved figures from the period and, indeed, from much earlier — Eve Arden, Frankie Avalon, even Joan Blondell — and then does nothing with them. Stigwood and Carr's approach to film-making is that of a trainspotter: They've checked Sid Caesar off the list, so why worry that the guy has no funny lines? Again, this kind of works. Joan Blondell is just right as the waitress, Eve Arden as the principal, and they get by on likeability. Even unfunny Sid does and, if Carr can do that to as famously unlikeable a guy as Caesar, he must have something going for him.

Of course, the picture does have the undoubted chemistry of its two star performers, John Travolta and his dancing bottom. Travolta's butt needs no big numbers: even walking through the cafeteria, it wiggles across the screen far more fetchingly than those of the girls of Rydell High. It's just a shame that this love affair between young John and his posterior has to be conducted in the superfluous presence of gooseberry Olivia Newton-John. When the "National Bandstand" television show comes to Rydell, Olivia says, "I hope I don't get camera fright." Bit late to worry about that.

Four decades on, at a time when it would come as no surprise to see Justin Beiber playing a US Treasury Secretary with Miley Cyrus as a feisty head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the most striking thing about Grease is how old everyone looks. No wonder they had to get Eve Arden and Sid Caesar to play the Rydell High faculty: the schoolkids all look about 35. If you were a high schooler yourself the first time you saw it and thought, "Wow! I wish I looked liked those guys", don't worry: chances are by now you do. Stockard Channing as the tough gal Rizzo is the nearest thing to a great performance, but Jeff Conaway, as the head of the T-Birds, has a plausibly small-town cool. The only exception to the general thirtysomething casting is a woman in late-middle age who cuts in on the dancing Travolta at the hop. "Ah-ha!" you say. "Here's his mother, come to take him home." But no; apparently, this is the local nympho from St Bernadette's.

The romance operates on a karaoke level: You're aware that there's really no "Danny" or "Sandy", but it's fun to watch John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John pretending to be them. Travolta looks incredibly camp during basketball practice and pulls off a superbly metrosexual vowel sound at the end of his duet with Livvy — "But eaueaeau those Summer Nights." Eaueaau indeed. But Livvy's leather turn in "You're The One That I Want" remains one of the great musical moments from post-Golden Age Hollywood. Grease will always be watchable: It's less a musical about high school than the acme of high-school musicals - like going to see a bunch of familiar faces goof around and sing and pledge undying love for a couple of hours. That's the groove it's got going for it, and probably always will have. It is a very particular skill to be able to see the potential in an unpromising piece of source material - in this case, a mediocre stage musical - and to transform it into a worldwide transgenerational hit. Robert Stigwood had that skill, and for a few amazing years lightning struck. Rest in peace.