It is a matter of regret that, among the many celebrations for this year's Sinatra centennial, nobody decided to release a compilation CD called Frank Sinatra Sings The Sacroiliac Songbook. It's more extensive than you might think. Here's Sinatra in 1949, doing the entirely fictional dance craze, "The Hucklebuck":

It is a matter of regret that, among the many celebrations for this year's Sinatra centennial, nobody decided to release a compilation CD called Frank Sinatra Sings The Sacroiliac Songbook. It's more extensive than you might think. Here's Sinatra in 1949, doing the entirely fictional dance craze, "The Hucklebuck":

Push your partner out

Then you hunch your back

Start a little movement

In your sacroiliac...

Here he is again in 1962, doing a rather less fictional dance craze in "Everybody's Twistin'":

There's a-hoppin'

And a-boppin'

Sacroiliacs a-poppin'...

And Sinatra, not dancing at all, in 1965:

Man in the looking glass, smiling away

How's your sacroiliac today?

For those under a certain age, the sacroiliac is the ligament that connects the sacrum to the ilium and whose smooth operation is necessary to a life free of lower back pain. If you're over a certain age, chances are you know that already. That last sacroiliac serenade is "The Man In The Looking Glass" by Bart ("Fly Me To The Moon") Howard. In 1965, Sinatra was approaching his 50th birthday. On the one hand, life was a blast: He was the swingin' bachelor, high-rollin' with his pallies in Vegas. On the other hand, he was feeling, if not in his actual sacroiliac then at least in his metaphorical one, the march of time.

So he decided to make an autobiographical album about entering autumn - September Of My Years. These days, 50 isn't the September of your years, more like early May, because 50 is the new 30, or the new fourteen-and-a-half, in our infantilized culture. But even then making an album about how old you are (actual song title: "How Old Am I?") was unusual. One recalls the sensitivity of even as timeless an icon as Cary Grant when a newspaper fact-checker wired his press agent: "How old Cary Grant?" Grant's reply: "Old Cary Grant fine. How you?"

But how old Frank Sinatra? He figured there was a whole album in that. As I wrote back in the very first entry of this series:

I used to think the idea was nothing more than Sinatra contrarianism: At a time when most celebs cling ever more fiercely to lost youth, he embraced premature old age. But Sinatra scholar Will Friedwald makes the point that "many of Sinatra's closest associates bought the farm while they were in their fifties". In the preceding decade, he'd lost his old boss, Tommy Dorsey; his first great arranger, Axel Stordahl; his record producer at Columbia, Manie Sachs; his longtime first violinist, Felix Slatkin - and many of the jazzers he most admired, such as Billie Holiday, died even younger. So it's entirely possible he and his arranger Gordon Jenkins were completely sincere in their intimations of mortality. It's a beautiful album: a couple of remakes - "September Song" (of course) and "Last Night When We Were Young" - and a lot of new material by fellows on the fringes of the Sinatra circle - "The Man In The Looking Glass", "I See It Now", "When The Wind Was Green", "It Gets Lonely Early"... You get the gist early - the falling leaves, the graying hair, the days dwindle down to a precious few. Yet it never wears.

"Last Night When We Were Young" he'd originally done with Nelson Riddle a decade earlier. It was a Harold Arlen/Yip Harburg song they'd written for the opera singer Lawrence Tibbett to sing in a 1935 film called Metropolitan. He delivered it much as you'd expect an operatic baritone to do, and it was cut from the picture. Twenty years later, someone played him the Sinatra resuscitation of the song. At the end, Tibbett said: "Oh. I see." Meaning: Now I get it.

Many Frankologists think Sinatra should have got it, and left the Nelson Riddle chart as the last word instead of remaking it with another arranger. Gordon Jenkins is an oddly controversial figure in Sinatra circles. I noticed years ago that Frank's musicians tended to fall silent or grow evasive or, a drink or two on, downright hostile toward Jenkins. His orchestrations didn't have the harmonic richness of Riddle or Axel Stordahl or Don Costa, and he returned again and again to certain tricks - two-note string seesaws, one-fingered piano - but he was, as Sinatra understood, a master storyteller, which is a vital quality in arranging a song.

As for his fellow arrangers, they tended to speak warmly of him. Nelson Riddle said he "admired Gordon so much for having written" ...the arrangement of "Lonely Town"? No. He admired Gordon for having written the song "Goodbye", which Riddle professed to be "crazy about". Billy May said he'd "been a fan of Gordon's for a long time". For his exquisite ballad orchestrations for Nat Cole and Sinatra? Er, no. As May put it, "He was a good songwriter and wrote some beautiful songs, especially 'This Is All I Ask'."

In other words, Riddle and May are enthusing not about Jenkins the arranger but about Jenkins the songwriter. He was the only one of Sinatra's key arrangers to have a serious sustained songwriting career - "San Fernando Valley" was a monster hit for Bing, "When A Woman Loves A Man" was beloved by Billie, and Ella, and Peggy, and every other discriminating female vocalist. Sinatra sang Gordon Jenkins songs long before he asked Gordy to score a single LP track for him: He took a crack at "San Fernando" on the radio in the Forties, and had Axel Stordahl arrange "Homesick, That's All" for him, and Nelson Riddle arrange "PS I Love You" and the aforementioned masterpiece "Goodbye". When Jenkins came on board as a Sinatra arranger, Frank continued to sing his songs, culminating in the critically panned futuristic concept song-cycle The Future in 1979 and the very affecting ballad of attracted opposites, "I Loved Her", in 1981. He wrote both music and lyrics: "Words, music and orchestration by Gordon Jenkins - the triple threat," as Frank liked to say when performing a Jenkins song live.

In this case, Frank could hardly not ask Gordy to score September Of My Years, because the entire project began when Sinatra, in melancholy autumnal mood, chanced to hear a Jenkins song:

Beautiful girls

Walk a little slower

When you walk by me...

There's a lot of truth in that sentiment. As a man grows old, he learns that young love is one of the things you leave behind, that are lost to you. Other kinds of love take its place - warmer love, deeper love. But there will be moments when a head turns and her hair sways and you'll be momentarily reminded of when such fancies made a heart of leap. But it's not about romantic appetite anymore, just a wistful, warm nostalgia for something that can never come again. Sinatra was moved by the tenderness and sensitivity of that fragment from a Gordon Jenkins lyric, and with it was born the idea for an entire album of songs in an autumnal hue.

A lot of us have been touched by that line as the years roll by. Ages back, I was at a dinner party with Lionel Bart, composer of Oliver!, and Denis Norden, a mainstay of British telly and radio these last seven decades and the screenwriter of Buona Sera, Mrs Campbell, starring Gina Lollobrigida, Phil Silvers, Peter Lawford and Telly Savalas, whose plot is not dissimilar both to the boffo hit Mamma Mia and a much less successful Broadway musical called Carmelina with a pre-Sopranos Paul Sorvino.

Where was I? Oh, yes. Anyway, Denis Norden, Lionel Bart and I and a couple of others were having dinner and the conversation turned to songs you'd like sung at your funeral. And Denis said he wanted that one that went:

Beautiful girls

Walk a little slower

When you walk by me...

And we all loved the lines and we all knew the song, but none of us could remember the title. "Sinatra sings it," I said, "and Nat 'King' Cole."

"But what's it called?" asked Denis.

"'Walk A Little Slower'," said Lionel.

"'Beautiful Girls'?" I suggested.

There's a reason why none of us knew the title, as we'll come to in a moment.

The song was born in a postprandial stroll in 1956. One day Gordon Jenkins was in New York lunching with a couple of music publishing pals, and pickings were thin, and somewhere between the soup and cognac one of the guys jokingly suggests: "Gordon, we're not doing anything today. Why don't you go home and write us a hit?"

And Gordon says sure, why not? "Meet me around five o'clock, we'll have a drink, and I'll have a hit for you." And they all had a big laugh and parted company on the sidewalk, and Jenkins headed uptown. And round about 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue a building had been torn down and wooden fencing thrown up and, if you looked in through the little grilles that occasionally punctuated the wooden fence, you could see that a new skyscraper was under construction. And somewhere on the fencing one of the crew had scrawled:

Pretty girls, slow down when you walk by here.

That's it? That wistful, tender, melancholic sentiment that Frank Sinatra and Denis Norden and I had been so moved by was the work of some hardhat ogling stacked chicks as they wiggled through midtown Manhattan?

Oh, well. Gordon Jenkins was bowled over by the graffito. "That was like a cartoon when the light goes on in someone's head. I thought to myself, 'Oh, my God - where's the piano?'" He headed straight to the office of the publishers he'd been lunching with, found a piano, and got to work. First he explains the situation:

As I approach the prime of my life

I find I have the time of my life

Learning to enjoy at my leisure

All the simple pleasures...

Ira Gershwin and Larry Hart wouldn't have rhymed "leisure" (in the British pronunciation) with "pleasures". Would it have made so much difference, in lieu of "all the simple pleasures", to write "ev'ry simple pleasure" or some such? Tim Rice once described this to me as "Lewis Carroll rhyming", where you carry over the extraneous consonant to the vowel at the beginning of the next line. And so:

...all the simple pleasures

And so I happily concede

This is all I ask

This is all I need...

Gordon Jenkins wrote songs his entire life, but he wasn't your typical Tin Pan Alley formula guy. And so he wrote a 15-bar verse, with a pair of two-bar phrases with a quadruple rhyme ("prime of my life"/"time of my life"), a three-bar phrase with a feminine rhyme ("leisure"/"pleasure") and then a trio of two-bar phrases with a masculine rhyme ("con-cede"/"need"). Who writes like this? And how?

I've never been able to work out how Jenkins wrote his songs. In some of his later work, there seem to be far more chord changes than the ho-hum melody can support, almost as if he's orchestrating a tune that hasn't quite been written. On the other hand, there are some wonderfully freewheeling tunes on which a lyric is trying without much success to establish a structure. How did this one happen? The melodic stresses of "prime of my life"/"time of my life" and "leisure"/"pleasures" seem obviously to be there to accommodate a pre-written lyric. Yet who would write a pop lyric in such an unstructured way?

Did I mention we're still in the introductory verse? Only after "This is all I need" do we slide into the chorus:

Beautiful girls

Walk a little slower

When you walk by me

Lingering sunsets

Stay a little longer

With the lonely sea...

For years I thought the first line was actually "Beautiful girl, walk a little slower", which I wonder sometimes wouldn't have been better: a singular individual rather than merely womanhood in general. But maybe not. The second image is perhaps a bit over-familiar in pop songs, but the third is genius:

Children ev'rywhere

When you shoot at bad men

Shoot at me

Take me to that strange, enchanted land

Grown-ups seldom understand...

What a great scene: an old man passing a bunch of young tykes playing in a park. The rest of the song returns to more familiar generalities, very skilfully, but it's the vivid specificity of the walking girls and the boys going bang-bang that makes the song memorable:

Wandering rainbows

Leave a bit of color

For my heart to own

Stars in the sky

Make my wish come true

Before the night has flown

And let the music play as long

As there's a song to sing

And I will stay younger than spring.

Jenkins wrote most of the song at that office piano, then went back to his apartment and finished up. And at five o'clock he called his publisher pals and said: "I've got that song we talked about." And after he played it to them their reaction was: "Great! What's the title?"

And at that point the composer realized that a song that had everything was nevertheless lacking one vital ingredient: A title. What about that final line - "Younger than spring"? Um, no. Rodgers & Hammerstein got to that one in South Pacific. Nothing else in the chorus seemed to work. "Beautiful girls" and "Wandering rainbows" sound like song titles, but here they're only one in a series of injunctions. The middle section? That "strange enchanted land" is striking, but it refers only to the kids' games.

Eventually, a year and a half later, Jenkins settled on the penultimate line of the introductory verse: "This Is All I Ask." Which is certainly what the number is about, but it's a phrase from the verse. Half the singers of pop standards don't even sing the verse - and now here's a song whose title makes no sense without it - and, even with that solitary mention in the verse, doesn't exactly plant the name of it in your head. As witness me, Lionel Bart and Denis Norden straining to recall it all those years later.

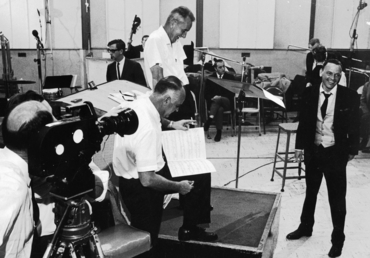

Still and all, it is a great song, as Sinatra recognized. And he and Jenkins made a great record of it, one in which Jenkins the orchestrator did full justice to Jenkins the songwriter. Stan Cornyn, the liner king, set the scene:

'You ready, Gordy?' Sinatra asked.

'I'm ready. I was always ready. I was ready in 1939.'

'I was ready when I was nine.'

Indeed.

Jenkins starts a song, conducting with his arms waist high, sweeping them from side to side. Not leading the orchestra, being the orchestra...

As Stan Cornyn explains:

Tonight will not swing. Tonight is for serious.

Vincent Falcone, Sinatra's musical director in the late Seventies and Eighties, put it this way:

When you hear a Gordon Jenkins arrangement, you know it immediately. Not that other arrangers weren't in his league, but when you have something that's so quickly recognizable, it sets you apart from other people. And you can't imitate Gordon Jenkins. You either were him or you weren't. That's why you don't hear anything like him, then or now, and that's what separates the men from the boys... If you took 'This Is All I Ask' and did it any differently, it wouldn't be right.

"The songs all had a thing about age, and growing older," Jenkins told Wink Martindale. "I was exactly the right age to do it, as he was. And we were talking about that on the date - that neither one of us could have made that album at any other time in our lives, except at that time."

Then again, if you don't care for Sinatra and Jenkins' version of "This Is All I Ask", there's always Fantasy Island's Herve Villechaize. When you're on a trivia quiz and someone asks what's the connection between Frank Sinatra and Herve Villechaize, the easy answer is James Bond. (Nancy Sinatra sang the theme song in You Only Live Twice; Herve is Christopher Lee's diminutive minion in The Man With The Golden Gun), but the cooler answer is "This Is All I Ask".

Sinatra kept "This Is All" in his stage act far longer than "Very Good Year", singing it regularly until well into the Eighties, his performance growing more heartfelt and elegaic over the years. The song seemed to humble him, as if he understood a little more with each tour date that time was the one thing all the swagger and style could not defeat. By then, Gordon Jenkins, like Stordahl and Riddle, was gone. Afflicted by Lou Gehrig's disease, injured by a car accident, Jenkins rallied to make one last great album of Sinatra saloon songs, She Shot Me Down, in 1981. Two-and-a-half years later, he was dead.

They were never buddies. That was, to one degree or another, a conscious decision. If you have a great professional partnership, you risk a lot taking it into after-hours. Bob Hope and Bing Crosby rarely saw each other outside the soundstage or broadcast studio; likewise Rodgers & Hammerstein away from Broadway theatres. At the studio door, as Gordy put it, "if Frank made a left turn after the gig, I made a right." Nevertheless, Sinatra treated Jenkins with a respect he'd didn't accord other arrangers. And at certain points in their relationship it extended into private matters, too. Half a decade after Jenkins' death, Sinatra told his son Bruce about sharing with Gordy "a lot of late-night, soul-searching talks over cocktails".

"They went to some quiet place and drank," said Bruce Jenkins, "and Frank would talk about Ava, and he'd talk about the chick from 'Goodbye' or whatever. They both had a lot of stuff like that. And it wore on 'em. And they didn't talk about it much, but to each other they could."

Which is one reason they worked together so well: Each knew what the other meant. So, like the song says:

...let the music play as long

As there's a song to sing

And I will stay younger than spring.

Frank and Gordy were always more suited to autumn, but they let the music play, and made a great record of one of the very best songs by one of Sinatra's closest collaborators. You can't hold the feeling: no matter how slow the beautiful girls walk, they walk and they're gone... But this song comes as near as any to capturing it for the ages.

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette is also counting down her Frank hit parade, and has a bouncier anthem of youthful regeneration at Number 29, "You Make Me Feel So Young". Meanwhile, Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints is counting down Sinatra's Top Ten Albums and at Number Seven has a classic Frank & Gordy collaboration, Where Are You? The Evil Blogger Lady has a different kind of mid-life crisis in a song from Sinatra's least successful concept album that never made much of a splash but was subsequently recorded by Nina Simone.

~Steyn's original 1998 obituary of Frank, "The Voice", can be found in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe, while you can read the stories behind many other Sinatra songs in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

15) NIGHT AND DAY

16) I WON'T DANCE

17) I'VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN

19) EAST OF THE SUN (AND WEST OF THE MOON)

21) A FOGGY DAY (IN LONDON TOWN)

24) OUR LOVE

27) FOOLS RUSH IN

32) I'LL BE AROUND

36) GUESS I'LL HANG MY TEARS OUT TO DRY

37) NANCY (WITH THE LAUGHING FACE)

38) SOMETHIN' STUPID

40) I GET ALONG WITHOUT YOU VERY WELL (EXCEPT SOMETIMES)

41) SOLILOQUY

42) THE COFFEE SONG

44) HOW ABOUT YOU?

46) LUCK BE A LADY

48) (AH, THE APPLE TREES) WHEN THE WORLD WAS YOUNG

49) I HAVE DREAMED

51) I'VE GOT THE WORLD ON A STRING

52) YOUNG AT HEART

54) BAUBLES, BANGLES AND BEADS

55) IN THE WEE SMALL HOURS OF THE MORNING

57) THE TENDER TRAP

59) WITCHCRAFT

60) EBB TIDE

61) COME FLY WITH ME

62) ANGEL EYES

63) JUST IN TIME

65) NICE 'N' EASY

66) OL' MACDONALD

68) AUTUMN LEAVES