For over half a century songwriters tried to get their best work to the best singer of the best songs. The sitcom "Frasier" devoted an entire episode to the proposition, after Dad revealed that he'd written a song for Frank, "You're Such A Groovy Lady". But he fared no better than U2's Bono and the Edge who as late as the mid-Nineties were still trying to get Sinatra to do their rather too head-on approximation of a saloon song, "One Shot of Happy, Two Shots of Sad". (Nancy eventually recorded it.)

For over half a century songwriters tried to get their best work to the best singer of the best songs. The sitcom "Frasier" devoted an entire episode to the proposition, after Dad revealed that he'd written a song for Frank, "You're Such A Groovy Lady". But he fared no better than U2's Bono and the Edge who as late as the mid-Nineties were still trying to get Sinatra to do their rather too head-on approximation of a saloon song, "One Shot of Happy, Two Shots of Sad". (Nancy eventually recorded it.)

But in the entire history of Getting Songs to Frank there are no luckier guys than Dave Mann and Bob Hilliard. One morning in late 1954 they happened to be walking up Broadway round about 55th Street when Hilliard spotted a couple of familiar figures up ahead. "Hey," he said, "there's Sinatra and Nelson Riddle." They were en route to Capitol Records' New York office for a meeting on their forthcoming album.

Both men knew Frank. Hilliard had written one of his Columbia hits, "The Coffee Song", and Mann had played piano on "I Fall In Love Too Easily" and many other early Sinatra records a decade earlier, including the beautiful solo on "I Begged Her". He and Frank had also shared a few tipples at Toots Shor's restaurant over the years. And Mann had worked with Nelson Riddle in the Charlie Spivak band. Thus they wouldn't exactly be accosting them in the street cold. So they called out, "Hey, Frank, Nelson!" And, after the usual pleasantries, Mann and Hilliard said they'd just written a song.

"Oh, yeah?" said Frank.

Dave Mann pulled a piece of paper from his pocket, and Sinatra gave it the once-over as they continued their stroll up to Capitol. Then he asked them to come in and demo the number. And at the end he re-folded the paper and handed it back to Mann. "Fellas," he said. "This is my kind of song."

And that's how easy it was.

That's how Dave Mann told it to me a couple of decades ago. And I noticed, on hearing versions of the story he told to others, that they departed from mine in a few details, but the essentials never changed. Even better, Dave Cavanaugh called from Capitol a few days later to tell Mann that Sinatra didn't just put it on the album, he made it the title track:

In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning

While the whole wide world is fast asleep

You lie awake and think about the girl

And never ever think of counting sheep...

Who else had Mann and Hilliard tried to pitch it to? Crosby? Nat Cole? Perry Como? No, they'd written it the night before. That's how even easier it was. They'd written it in the wee small hours of the morning while the whole wide world was fast asleep and a few hours later, when the whole wide world was wide awake, they sold it to Frank Sinatra. No sleepless nights, lying awake and thinking about the song, and counting all the singers who'd turned it down.

They'd been at Bob Hilliard's pad in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from New York City. It wasn't a work session: They'd spent the evening playing cards. But it was getting late, after midnight, and Dave Mann was itching to get back to town. And Hilliard said, "Nah, don't leave yet. C'mon, let's write a song." So Mann agreed to stay - reluctantly. Which is why it's such a short song. Just 16 bars of music by Mann. And two quatrains of lyric by Hilliard - the first four lines above, and the last four lines below:

When your lonely heart has learned its lesson

You'd be hers if only she would call

In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning

That's the time you miss her most of all.

Yet what else is there to say? You could try adding another 16 bars, but really, why bother? That's the whole story, right there. And that's why Frank Sinatra was able to glance at it on a New York street and figure he liked it. Harder to do that with "Lush Life" or the Soliloquy from Carousel.

The phrase "wee small hours" might strike one as at least partially tautological in that "wee" means "small", but the formulation goes back over a couple of centuries at least, to Robbie Burns, who, much like Sinatra, did his best work in "the wee sma' hours ayont the twal'" - ie, past midnight. By the 20th century the expression had spread far beyond Scotland. In 1913 the American journalist Joseph W Bryce used the phrase to open a bit of pastiche Burns:

In wee sma' hours ayont the twal

When eyelids droop at nature's call

And honest neebors gang to sleep

And gahists and warlocks o'er earth creep

I wandered thro' a lanely street

And there the ghaist of Burns did meet...

Mann and Hilliard used the phrase for a less specialized scenario - and Sinatra's album cover universalized it: In the wee sma' hours a man wanders thro' a lanely street, pursued by the ghaist of a lost love. It's such a good title - and such a good example of how a commonplace vernacular expression can be transformed by music - that you wonder why no songwriters had seized on it before. It's not clear that Mann and Hilliard fully realized what they had. Dave Mann scribbled the words and music on that piece of paper, tucked it in his pocket, and then headed back across the George Washington Bridge to his home in the city.

Later, for the published sheet music, they wrote an introductory verse, with a clock-chime tick-tock:

When the sun is high

In the afternoon sky

You can always find something to do

But from dusk till dawn

As the clock ticks on

Something happens to you...

Which is a by-the-book intro of the "and that's why I say..." school:

In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning...

Johnny Mathis, who recorded the song a couple of years after Sinatra, used the verse - mainly you feel to distinguish himself from Frank. A third of a century on, Carly Simon sang it on her famous record, memorably featured in Sleepless In Seattle. But it doesn't really add anything, does it? Sinatra always knew when not to record a verse - even when, as in this case, the verse had yet to be written.

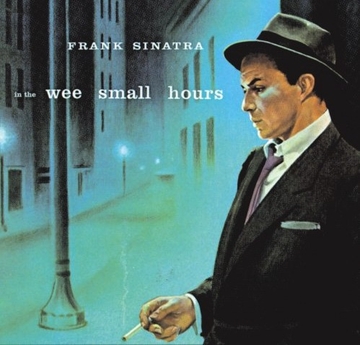

But he knew the eight lines and 16 bars of the chorus were just what he needed to tie his new album together. In The Wee Small Hours marked an important evolution in Sinatra's relationship with Capitol Records and Nelson Riddle, and in the evolution of his art. His previous Capitol LPs - Songs For Young Lovers and Swing Easy - were no more or less than what they say: songs that swing, songs of love. But with Wee Small Hours he was attempting to nudge the nascent LP form a bit further. The cover art revives the street lamp from Songs For Young Lovers, but now it's pure film noir: a lamp post on a deserted street after midnight, a pensive guy leaning against a wall, hat pushed back, cigarette in hand. What is this? The new Mickey Spillane? The poster for this week's Robert Mitchum movie? No, it's an album of pop songs, but with a difference: a prototype concept album, in which the songs didn't exactly tell a story - in the plotted sense of Jack meeting Jill, and then asking her to go up the hill, etc - but they did chart a mood and therefore had a dramatic arc. Later Frank would describe how he would write the song titles on bits of paper, lay them out on the table, and then shuffle them around until they settled into an order that felt right. The order on Wee Small is especially fine: "In The Wee Small Hours", "Mood Indigo", "Glad To Be Unhappy", "I Get Along Without You Very Well", "I See Your Face Before Me", "Can't We Be Friends?" ...get the picture?

But the ambitious form was only possible because of the content - because both Sinatra's vocal tone and his interpretative powers had matured. And, according to some, because Ava Gardner had just dumped him and he was spilling his guts out. In our piece on "What Is This Thing Called Love?", the song that opens Side Two of Wee Small Hours, I quote the composer Jule Styne, with whom Frank, post-Ava, had moved in:

I come home at night and the apartment is all dark. I yell, 'Frank!' and he doesn't answer. I walk into the living room and it's like a funeral parlor. There are three pictures of Ava in the room and the only lights are three dim ones on the pictures. Sitting in front of them is Frank with a bottle of brandy. I say to him, 'Frank, pull yourself together.' And he says, 'Go 'way. Leave me alone.' Then all night he paces up and down and says, 'I can't sleep, I can't sleep.' At four o'clock in the morning I hear him calling someone on the telephone. It's his first wife, Nancy. His voice is soft and quiet and I hear him say, 'You're the only one who understands me.' Then he paces up and down some more and maybe he reads, and he doesn't fall asleep until the sun's up.

In 1955 Sinatra was trapped in the wee small hours. What else was he going to sing about? Yet, while they're mopey loser downer ballads, this is a jazz album in which Sinatra, while straying true to the storytelling, bends and stretches and phrases more freely than ever before. And the heart of Riddle's sound for these torch songs of lost love is not the violins but, as Frankologist Will Friedwald points out, "a five-piece rhythm section, with bass, drums, rhythm guitar, and two keyboards - Bill Miller in his regular spot at the piano and guest Paul Smith on the celesta". And the strings, when he does use them, are not the sugarcoating of romance that even Riddle's Nat Cole charts fall prey to, but subtly shaded intersections of violins and 'celli blending with the winds.

Band and singer are as one, from the brief celeste-and-strings intro that sets the stage for Frank's first bite at the title line. Most singers, sometimes even very good ones, don't do anything but sing big on the ends of lines. Here Sinatra does the opposite, easing off on the word "morning" and somehow touching loneliness with tenderness. He knows exactly how much dramatic weight to give each word: Listen to the aching "only" in "You'd be hers if only she would call", and then compare his reading of this line in the first chorus and its reprise in the out-chorus. It's not really a "reprise" at all: the clock has ticked on, to the next stage of despair. Sinatra's interpretation here is as great as anything he's ever done.

Frank returned to the song one-and-a-half times. In 1963, he re-recorded "Wee Small" for the LP Sinatra's Sinatra, "a collection of Frank's favorites", and an album that seems to have no other purpose than to grab a bunch of his Capitol and Columbia hits and appropriate them for his new Reprise label. For most of the tracks he sticks close to the originals, but "In The Wee Small Hours", again with Riddle, is lighter and brighter, an older, worldlier Sinatra's reflection on how bad things can get - whereas on the original he's singing about how bad things are, he's living it.

Another three decades later and Sinatra was making his celebrity duets CD, in which he went into the studio and sang his hits in his arrangements and then Phil Ramone found some contemporary star whom Frank had never met and in many cases had never heard of (Luther Vandross, Anita Baker) to edit into the track. Among the songs selected was "Guess I'll Hang My Tears Out To Dry", but for this track Ramone and conductor/arranger Pat Williams decided to do something a little different and make it a medley with "In The Wee Small Hours", which Carly Simon (of the aforementioned Sleepless In Seattle version) would sing contrapuntally. If you don't quite see the need for this, be grateful for small mercies: The original plan was for Miss Simon to insert herself into the aged Sinatra's last magnificent recording of "One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)". But fortunately Miss Simon chanced to be on the board of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and felt that recommending one more for the road might cause her a few problems. So instead they shoehorned her "Wee Small" into Frank's "Tears Out To Dry". As with Samuel Johnson on female preachers, you're impressed not that it's done well but that it's done at all: Carly Simon had to sing her part down the phone to Capitol in Los Angeles on an ISDN line on which there was a slight delay, which meant she had to anticipate and come in slightly early every time, even as Frank was backphrasing like crazy. As I said, whether it was needed is another matter, but I can't think of many singers who'd want to lay down a vocal track like that.

Dave Mann's other hit is "There! I've Said It Again", which was a big hit for Vaughn Monroe in 1945 and a generation later for Bobby Vinton, the last American Number One record before the Beatles' "I Want To Hold Your Hand" heralded the British Invasion of the Billboard charts. Bob Hilliard had had his last Number One hit just a few months earlier, "Our Day Will Come" by Ruby and the Romantics. But "In The Wee Small Hours" is the song that became not a hit but a standard. There are now well over 500 recordings of it - because, walking down the street one morning, Mann and Hilliard ran into Frank Sinatra; and, because he was first to record it, everybody else followed.

But the song benefited too not just from Sinatra's performance but from the long-form masterpiece to which it lent its name. If you want the essence of what the singer accomplished on the Small Hours album distilled into one sentence, consider the view of one of his professional colleagues. "Last Night When We Were Young" was written in 1935 by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg - and Arlen to the end of his life considered it the greatest of all his songs. Nevertheless, it was slung out of three movies because it was "too sad". The first person to record it was Lawrence Tibbett, a baritone with the Metropolitan Opera who in the Thirties enjoyed a brief film career. Tibbett's performance of "Last Night When We Were Young" was supposed to be part of the film Metropolitan, but in the end they junked it and used a bit of instrumental on the closing titles. Tibbett delivered the song much as you'd expect an operatic baritone to do.

"Last Night When We Were Young" didn't do much in the ensuing years, but then, 20 years later, someone brought Tibbett a copy of In The Wee Small Hours and he saw on the track list that old song he did in 1935 that went nowhere. And he put it on the record player and listened to it - Sinatra's voice and Riddle's arrangement combining to create one of the great morning-after ballads.

And at the end of it Lawrence Tibbett said, "Oh. I see." Meaning "Now I get it": Tibbett had sung the notes. Sinatra had lived the drama.

There must have been other singers in 1955 listening through to that LP and saying, "Oh. I see." This was the album, more than any other, that separated Sinatra from other popular singers, and made him the gold standard. He was in a certain sense pioneering, in both form and content, and his approach opened up new possibilities for songwriters inclined to mood and character and drama. Hitherto, Broadway shows had title songs, and Hollywood musicals had title songs, but "In The Wee Small Hours Of The Morning" has the distinction of being the first title song for a Sinatra concept album: Written in the wee small hours, pitched to Frank the following day, and a signature song ever after.

In The Wee Small Hours was recorded over five nights at KHJ in Hollywood in February and April 1955. On one of those five nights, Sinatra wanted to hear back a couple of the takes. The band cleared out, and so did Riddle. And Frank listened back to what he wanted to hear, and then the engineers left. And then he poured himself a cup of bottom-of-the-pot stewed coffee and, amid the chairs and music stands, slumped down, crossed his legs and pushed his hat back on his head. He hummed a few bars of something as the night janitor came in and started cleaning up the place.

"Jeez," said Frank. "What crazy hours we got. We should've been plumbers, huh?"

Sinatra at home, in the wee small hours.

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has also launched a Frank countdown. She's up to Number 41 - another classic from the Wee Small Hours set, "I'll Be Around". The Evil Blogger Lady is also brooding in The Wee Small Hours with "I Get Along Without You Very Well (Except Sometimes)". Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints is likewise counting down his own Sinatrapalooza, and at Number 42 he's in a Wee Small mood, too, but with a live version of one of the album's mini-masterpieces, "When Your Lover Has Gone".

~Steyn's original 1998 obituary of Frank, "The Voice", can be found in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe, while you can read the stories behind many other Sinatra songs in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

15) NIGHT AND DAY

16) I WON'T DANCE

17) I'VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN

19) EAST OF THE SUN (AND WEST OF THE MOON)

21) A FOGGY DAY (IN LONDON TOWN)

24) OUR LOVE

27) FOOLS RUSH IN

32) I'LL BE AROUND

36) GUESS I'LL HANG MY TEARS OUT TO DRY

37) NANCY (WITH THE LAUGHING FACE)

38) SOMETHIN' STUPID

40) I GET ALONG WITHOUT YOU VERY WELL (EXCEPT SOMETIMES)

41) SOLILOQUY

42) THE COFFEE SONG

44) HOW ABOUT YOU?

46) LUCK BE A LADY

48) (AH, THE APPLE TREES) WHEN THE WORLD WAS YOUNG

49) I HAVE DREAMED

51) I'VE GOT THE WORLD ON A STRING

52) YOUNG AT HEART