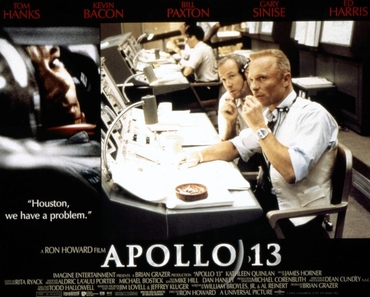

For whatever reason, it feels a fairly muted Independence Day this Fourth of July. So I thought for our Saturday movie date a tale of American daring and ingenuity triumphing against the odds. This was the big holiday movie a score of Fourths ago, a Ron Howard blockbuster that's essentially an adaptation of a famous line: "Houston, we have a problem" - from 1995, Apollo 13:

Millions of people across the planet can dimly recall watching the progress of NASA's ill-fated 1970 moonshot on TV — or, at least, dimly recall the happy ending. And what's the point of a picture where you walk in knowing the ending? But figure it the other way: how often have you walked into a Hollywood movie and didn't know the ending? Okay, Casablanca maybe, but since then? Don't tell me you were surprised that Harry wound up with Sally or that Schwarzenegger terminated the bad guys? Apollo 13 reminds us that, with films, it's the journey, not the destination.

That said, I don't remember looking forward to it back in 1995. In the 25 years between Apollo 13 the moon shot and Apollo 13 the movie, the space program and anything connected with it became one of the most surefire yawneroos around. The last thing I remember is - what? that soi-disant amazing Hubble telescope with its never-before-seen pictures of assorted shades of dark grey? By now, according to what they told us back in 1970, we were supposed to have timeshares on Mars and be up there flying in jetpacks round to the neighbors for a slap-up dinner of colored pellets. But the futuristic future never happened and we have to make do with a cordless phone that plays Miley Cyrus. And, in retrospect, Apollo 13 can be seen as NASA's last shooting star—a lesson, in a technological age, that the triumph of the human spirit is still the most thrilling story of all.

Howard's film skewers the moment. Seen from today, 1970 is like landing on another planet: the NASA wives favor hairstyles that look more like intergalactic police helmets or the bird's-wing doors on a DeLorean automobile. Otherwise, Howard downplays the period's quaintly lurid quality: the photography is flat and prosaic, as if aspiring to the condition of a documentary - although the score by James Horner (who died in a plane crash just a few days ago) seems to be shooting for epic adventure: In an odd directorial decision, Howard lets Horner drown the roar of take-off in soaring strings. But, poised somewhere between these two extremes, Howard hits the right tone: nothing dates quicker than a vision of the future, and the buoyant reach-for-the-moon optimism at NASA seems less like a world trembling on the brink of a space-age future and more like a coda to an age of buoyant optimism back on earth. Even then, public interest in the final frontier had already peaked: when the astronauts beam their stiltedly larky live TV broadcast back to earth, the networks dump 'em "'cause they make going to the moon real boring". Even back at HQ in Houston, the technicians would rather watch the football game.

For Howard, television is part of the story. The film flips to "The Dick Cavett Show": Cavett is in the middle of his monologue, doing astronaut jokes, when suddenly he's interrupted by an "ABC Special Report". From hereon, the film's structure is simple. divided between archive news footage, mainly from Walter Cronkite on CBS, and the astronauts up in space frantically trying to figure out what's gone wrong; between the tentative, speculatory story as it unfolded at the time, and the way it was for those involved.

It's sobering to reflect that, for this kind of modern-age cine-history, celebrity is a minimum entry requirement. You can't have actors playing Cronkite and Cavett, because, to Americans of 1995, these guys are too real for any substitutes to pass muster. But the astronauts? Lovell, Swigert, and Haise? Who now remembers them? They didn't just read teleprompter for a living; they did what very few humans have ever done: they broke the bounds of earth; they embarked on a spectacular mission, and then, when that went wrong, they saved the day even more spectacularly. But, while every tic of Cronkite and Cavett is preserved on film, the astronauts are invisible in their own movie. As Jim Lovell, Tom Hanks is Tom Hanks; as Jack Swigert, Kevin Bacon is Kevin Bacon; and Fred Haise is the one who's played by wossname, Bill Pullman. No, wait, Bill Paxton. Jim Lovell appears in the film as the commander of the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima, and Mrs Lovell is in the crowd scene at the launch.

Unsurprisingly, the picture's third element — the men's families — makes for the weakest scenes: the most important relationship in the film is not between the crew and their wives, but between the crew and that capricious mistress technology. The scenes in space are great, simultaneously claustrophobic and panoramic: a pokey module (the weightlessness is especially well done) with a vast, silent blackness pressing against the windscreen. Better still are the earthbound moments in Houston*, with Ed Harris in superb form hustling the boffins to improvise DIY oxygen kits for the astronauts, made from the polythene wrappers of their spaceship manuals. Gary Sinise is also on hand, having been invited by Howard to read for any character in the dramatis personae, and opting for command module pilot Ken Mattingly.

Is Tom Hanks really Lovell? Is Kevin Bacon a plausible Swigert? Who cares? The film works as a tense techno-thriller pitting a crew of arbitrary everymen against the whims of their ship. And, when it's over, you realisze that, yes, you knew the ending but it wasn't the one you'd remembered: sure, the boys got back safely, but you leave regretting that NASA was never able to use that success to capture the popular imagination again. Apollo 13 is an exhilarating evocation of a rare moment when science was in tune with man's dreams.

*CORRECTED: I'd originally said Cape Kennedy.

~Mark writes on the space program and why we haven't been to the moon in over four decades in his bestselling book After America, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.