On the CD of his live show at the Golden Nugget in Vegas in 1987, Frank Sinatra hard-swings his way through "What Now, My Love?" and then settles back as the strings start up. "Hoagy Carmichael," he says. "It is rumored he wrote this song":

On the CD of his live show at the Golden Nugget in Vegas in 1987, Frank Sinatra hard-swings his way through "What Now, My Love?" and then settles back as the strings start up. "Hoagy Carmichael," he says. "It is rumored he wrote this song":

I Get Along Without You Very Well

Of course I do

Except when soft rains fall

And drip from leaves, then I recall

The thrill of being sheltered in your arms

Of course I do

But I Get Along Without You Very Well...

It's not really a "rumor" that Hoagy Carmichael wrote this song. It's fairly well established that he wrote at least half of it. But rumor has certainly attached itself to the matter of the other half.

Hoagland Carmichael was a composer first and lyricist second. When no one was to hand, he was happy to write his own words for "Rockin' Chair" and "Hong Kong Blues". But, even when he didn't, the lyrics by other men seem to convey something of his persona: "Ole Buttermilk Sky", or "Memphis In June", or "My Resistance Is Low" - words by, respectively, Jack Brooks, Paul Francis Webster and Harold Adamson. His music helped a trio of big lyricists get their careers off the ground - Mitchell Parish with "Stardust", Johnny Mercer with "Lazybones", and Frank Loesser with "Heart And Soul". But Carmichael was just as content to use whoever happened to be around. It was a stone-cutter from New Bedford, Indiana, Fred Callahan, who provided the words to one of his earliest melodies, "Washboard Blues". If Mr Callahan ever felt the urge to take a break from cutting stone and write a second song, posterity does not record it.

A few years later, the saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer said to Hoagy, "Why don't you write a song called 'Georgia'? Nobody lost much writing about the south." Carmichael agreed that that was certainly true, and Trumbauer added some further advice: "It ought to go 'Georgia, Georgia...'" Within a week, Hoagy had the music and was pacing the floor trying to think up a lyric. His college roommate Stu Gorrell volunteered his assistance, and the composer said he'd split the royalties.

"How much in cash, Hoagy?" asked Stu. Just an old sweet song keeps cash-flow on his mind.

But the story of the most unlikeliest of Hoagy Carmichael's one-hit writing partners goes back to 1924, before he'd written even "Washboard Blues", back when he was a jazz-obsessed law student at Indiana University. One day a chum showed him a magazine clipping of a poem he thought Hoagy might like. He did, and it occurred to him it might be something he could set to music. So he scribbled the words out on an envelope and stuck it in his pocket. And, what with jazz and beer and girls and all the other distractions of campus life, he promptly forgot all about it.

Fifteen years later, he was a successful songwriter living the good life in Hollywood. And one day, clearing out some things, he came across that old envelope with the scribbled-out poem. And he remembered how much he liked it - and this time he got around to writing a tune for it - 64 bars, twice as long as a typical song, and with more repeated notes than any other Hoagy Carmichael composition before or after, starting with the front half of a very long title:

I Get Along Without You Very Well

Of course I do

Except perhaps in spring...

Frank's pal Alec Wilder was a big fan of Hoagy Carmichael's jazzy side, but he had mixed feelings about this offering. On the one hand, "it is unlike any other popular song I know". On the other, "I respect it more than I like it". He found it "without an ounce of cleverness" and harmonically stagnant. He considered it "solely as a melodic line", and of that he cared only for the middle section:

What a guy

What a fool am I

To think my breaking heart could kid the moon

What's in store?

Should I phone once more?

No, it's best that I stick to my tune...

And Carmichael does, returning to the main theme that, Wilder sniffed, "borders on the saccharine". It's certainly somewhat unHoagy-like, if your idea of Hoagy Carmichael is "Two Sleepy People" or "Up A Lazy River". I think the difference is that, for the first time, he was setting a text - and not just a pop lyric but a "poem". There is a certain formality to its heartache. The song, pronounced Wilder, falls "very nearly into a class I choose to call Ladies' Luncheon Songs." When I first read that line as a teenager, I had no very clear idea what a Ladies' Luncheon Song was. But, as things turned out, it wasn't so far off the mark.

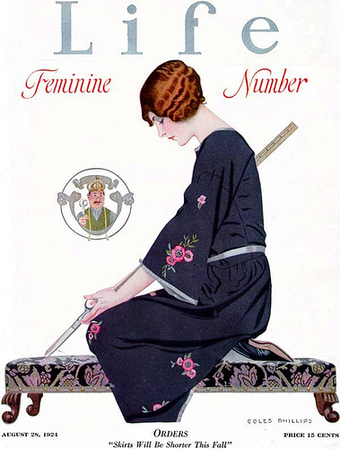

At any rate, Carmichael now had a problem: he had a melody and he had a lyric, but he couldn't get the song published until he found out the identity of his writing partner. The only clue on the envelope was "JB", which he'd copied down from the author credit at the foot of the poem in the magazine. He remembered the magazine was Life - not Henry Luce's photojournalist companion to Time, but an earlier and, to my tastes, somewhat livelier publication of jokes, stories and social observation that had had a good run since 1883. Unfortunately, it had folded in 1936. What about the Indiana U classmate who'd brought the poem to his attention? Carmichael couldn't even remember who it was. Someone suggested Walter Winchell might be able to help. The famous columnist was a friend of Hoagy's who'd been so assiduous in his championing of "Stardust" that for a while it was known as "the Walter Winchell song". So, for three weeks, Winchell talked up the new Hoagy Carmichael song on his radio show, and begged the author to come forward. From Seattle to Miami, hundreds of listeners claimed to have written the poem.

Fortunately, some old hands from Life magazine heard the show, rummaged through their archives, and eventually tracked down the real "JB" to Philadelphia: Jane Brown, now Jane Thompson. In the heyday of Life and similar publications, amateur versifiers such as Mrs Thompson had filled up any spare room at the foot of the page. But she was now a widow in her seventies, and not much of a radio listener or a newspaper reader. Nevertheless, she and the composer struck a deal, and it was announced that Dick Powell would introduce the song on his radio show on January 19th 1939.

The day before, January 18th, Mrs Thompson died. The following night, millions heard Hoagy Carmichael's setting of the poem she'd written 15 years earlier.

I like a good and-then-I-wrote anecdote as much as the next chap, but this one seemed too good, and, back in my teen disc-jockey days, I felt vaguely guilty retailing this one, certain somewhere deep down that it was all a lot of hooey. A few years later, with a bit of time on my hands and a little savvier on the research front, I thought I'd look into it.

For a start, look at our headline: "I Get Along Without You Very Well (Except Sometimes)." What's up with that parenthesis? The phrase "except sometimes" doesn't appear anywhere in the song, although the first half of it shows up twice:

I Get Along Without You Very Well

Of course I do

Except when soft rains fall...

Still "Except Sometimes" seems an odd phrase to tack onto the title but not use in the lyric. It all made sense when I finally saw "JB"'s original poem as published in Life in 1924. The title?

Except Sometimes

I'm not sure I don't prefer that as a song title. A couple of years ago, Molly Ringwald - yes, that Molly Ringwald, Pretty In Pink, Sixteen Candles, Eighties icon - put out a neat little standards album. That's her family background - her dad's Bob Ringwald, a fine pianist. And Miss Ringwald's CD is a pleasant listen, and includes "I Get Along Without You Very Well", but what really tells you she knows her stuff is her choice of album title: Except Sometimes. It's too good to get lost in the parentheses.

There are certain differences between Mrs Thompson's poem and Carmichael's song:

I Get Along Without You Very Well

Of course I do

Except when soft rains fall

And drip from leaves, then I recall

The thrill of being sheltered in your arms

Of course I do...

Here's how the Ladies' Luncheon lady had it originally:

I get along without you very well,

Of course I do.

Except the times a soft rain falls,

And dripping off the trees recalls

How you and I stood deep in mist

One day far in the woods, and kissed.

But now I get along without you — well,

Of course I do.

That "deep in mist" "far in the woods" is awfully good, and it's a shame to lose it. But, even at 64 bars chock-a-block with repeated notes, there's only so much room. Mrs Thompson continues:

I really have forgotten you, I boast,

Of course I have.

Except when someone sings a strain

Of song, then you are here again;

Or laughs a way which is the same

As yours; or when I hear your name.

I really have forgotten you — almost.

Of course I have.

Carmichael junked the "strain of song" couplet, which is no great loss. But he keeps almost everything else:

I've forgotten you just like I should

Of course I have

Except to hear your name

Or someone's laugh that is the same

But I've forgotten you just like I should...

You can see what young Hoagy liked about Mrs Thompson's poem. Ninety years ago, this was a very literate culture, and an editor soliciting contributions could rely on a certain baseline middlebrow proficiency. JB's submission is very adroitly done, with the recurring "Of course I do/have"s, and the "But now I get along without you - well/Of course I do" and "I really have forgotten you - almost."

But that's all there is.

So, as it turns out, the only bit that Alec Wilder liked was the one section where Carmichael wasn't fettered by Mrs Thompson's words and just wrote the whole thing himself:

What a guy

What a fool am I

To think my breaking heart could kid the moon

What's in store?

Should I phone once more?

-which, even if you didn't know which was Mrs T's and which was Hoagy's, has a different sensibility and more conventional imagery. Oh, and Mrs Thompson didn't have a telephone.

How about all that Walter Winchell stuff? Well, in his biography of Carmichael, Richard M Sudhalter uncovers an item in Winchell's Broadway column suggesting that Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians premiered "Hoagy Carmichael's latest love lilt" on December 26th 1938. But presumably this was a stage performance only - and quite possibly instrumental only. The contract with Mrs Thompson was not signed until January 6th 1939.

They were cutting it exceeding fine. Jane Brown Thompson was in poor health. Twelve days later, at home in Philadelphia on Wednesday evening, January 18th, Mrs Thompson died of a thrombosis. Twenty-four hours later, Dick Powell introduced her song to the nation - and she never heard it. A month later, Red Norvo's record, with Terry Allen's vocal, entered the charts.

A few days after that the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra came to Indianapolis to play the Lyric Theatre and asked Hoagy Carmichael to appear as a guest on the show. He agreed, as long as his mother could come along and play something, too. So on March 1st 1939 The Indianapolis Star sent Corbin Patrick round to the Carmichael home at 3120 Graceland Avenue to watch mother and son rehearsing. Mr Patrick reported:

His latest hit, 'I Get Along Without You Very Well,' will be featured Saturday night on the Hit Parade radio broadcast. This song was based on a poem given Hoagy by a friend 10 years ago. When the song was written he conducted a quest for the author of the poem with the aid of Walter Winchell. They finally found her, Mrs. Jane Brown Thompson of Philadelphia, Pa., but she died Jan. 19 without having heard the song.

By all accounts, Mrs Carmichael stole the show at the Lyric Theatre, from her son and from Tommy Dorsey. A year later, Dorsey had a new boy vocalist, and, if he ever thought the song would be just right for Frankie, he doesn't seem to have done anything about it. Sinatra had to wait till 1955, and the first concept album - by Frank or anyone else. It's perfect for In The Wee Small Hours. On ballads, Sinatra the singer liked to have something for Sinatra the actor to play. The most dispiriting moments in his oeuvre are some of the soft-rock ballads from his late years when he's trying to invest some piece of schlock with a meaning that just isn't there. But with Carmichael and Thompson's song something in the situation touched him: I get along without you very well - except....

He sings it beautifully on the album - I always liked the modulation, and I was thrilled, on meeting Sinatra's pianist Bill Miller, to discover that he did, too. Frank kept it in his book, not quite to the end but almost. He delivered a fine performance of it at the Royal Festival Hall in 1970 (part of the new Sinatra London box set), and on other occasions over the next two decades. The first time I heard him do it, you had the sense that "Strangers In The Night" and "For Once In My Life" were for the customers, but this one was just for him - and, if no one wanted to hear it, that was their problem. At 40, 60, pushing 80, he always tapped into the situation: a guy trying to fool himself that he's not still spilling his guts out:

I Get Along Without You Very Well

Of course I do

Except perhaps in spring

But I should never think of spring

For that would surely break my heart in two.

Jane Brown Thompson, born in Bremen, Indiana in 1867, never heard Sinatra or anybody else sing the song. She never heard the name "Sinatra". But he loved her song as much as he loved Cole Porter or Rodgers & Hart.

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has launched her own Frank countdown. She has another In The Wee Small Hours track at Number 65: "Ill Wind." Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints is also counting down his Top 100 Sinatra tracks, and he has a live version of a Small Hours song at Number 42: "When Your Lover Has Gone." And the Evil Blogger Lady is also getting along very well.

~You can find the stories behind many more Sinatra songs in Mark Steyn's American Songbook, while Steyn's original 1998 obituary of Frank, "The Voice", can be found in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

15) NIGHT AND DAY

16) I WON'T DANCE

17) I'VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN

19) EAST OF THE SUN (AND WEST OF THE MOON)

21) A FOGGY DAY (IN LONDON TOWN)

24) OUR LOVE

27) FOOLS RUSH IN

32) I'LL BE AROUND

36) GUESS I'LL HANG MY TEARS OUT TO DRY

37) NANCY (WITH THE LAUGHING FACE)

38) SOMETHIN' STUPID