"Fools Rush In" isn't thought of as a Frank Sinatra song. If you were anywhere near a jukebox or a transistor radio in the early Sixties, you'll think of it in Ricky Nelson's bouncy-bouncy teenypop arrangement. And, as I pointed out our two-part Johnny Mercer podcast, many pop acts since have tended to cover not so much the song, but that Ricky Nelson version of it: in the Seventies Elvis did, and in the Eighties Bow Wow Wow, and only a couple of years back She and Him.

"Fools Rush In" isn't thought of as a Frank Sinatra song. If you were anywhere near a jukebox or a transistor radio in the early Sixties, you'll think of it in Ricky Nelson's bouncy-bouncy teenypop arrangement. And, as I pointed out our two-part Johnny Mercer podcast, many pop acts since have tended to cover not so much the song, but that Ricky Nelson version of it: in the Seventies Elvis did, and in the Eighties Bow Wow Wow, and only a couple of years back She and Him.

But once upon a time the song was new, and Frank Sinatra was the guy singing it, up on stage with Tommy Dorsey and the orchestra:

Fools Rush In

Where angels fear to tread

And so I come to you, my love

My heart above my head...

Sinatra joined the Dorsey band in January 1940, and he was in the studio recording "Fools Rush In" two months later. The Frankie of the Tommy Dorsey era is what Will Friedwald calls "a virginal Sinatra, if such a thing is imaginable". Well, it's imaginable on "Fools Rush In": He's young and he doesn't know how deep the folly of love can hollow you out - as he did by the time of "I'm A Fool To Want You". Don't you know, little fool, you never can win? No, he doesn't know, not in March of 1940.

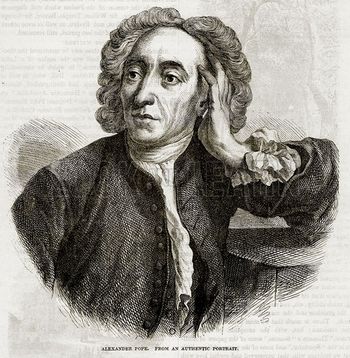

Did he get the literary reference? It's from Pope. That's Alexander Pope, poet, 1688-1744. I did a lot of Pope when I was at school - Rape Of The Lock, The Dunciad - but I don't know how large he loomed at Demarest High in Hoboken, and in any case Frank's attendance record was fitful. But, if you get out Pope's poem An Essay On Criticism (1711), you'll find way down toward the end:

Nay, fly to Altars; there they'll talk you dead;

For Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread.

It's had a lot of mileage over the years - Edmund Burke used it in Reflections On The Revolution In France, and Lincoln in his Peoria speech, attributing it to "some poet". I mentioned a week or so back that there's a CD to be made called Classical Frank. Well, you could get at least an EP out of Frank Sinatra Sings Alexander Pope's Greatest Hits. was. In 1955, for In The Wee Small Hours, he sang a Rodgers & Hart song whose chorus begins:

Fools rush in

So here I am

Very Glad To Be Unhappy...

Six years earlier, in a rather labored duet with Pearl Bailey, he'd recorded a novelty song called "A Little Learnin' Is A Dangerous Thing". That's Pope, too. Same poem, An Essay On Criticism:

A little Learning is a dang'rous Thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring:

An Essay On Criticism also includes "To err is human, to forgive divine", which has turned up in various songs over the years, but none recorded by Sinatra.

Rube Bloom wasn't thinking of Alexander Pope when he wrote the tune, but rather of Frank Capra's Lost Horizon, the Ronald Colman movie adapted from James Hilton's blockbuster novel set in the utopian lamasery of Shangri-La. So that's what he called his melody. Bloom was self-taught musically and didn't always think in terms of songs. He'd noodle his compositions on the piano and, because he was unable to write them down, had a musical secretary on hand to get it all on paper. He foresaw "Shangri-La" as an instrumental, but Johnny Mercer had returned from Hollywood to work with Bloom on a Broadway revue, Lew Leslie's Blackbirds of 1939, and, when the show folded in a week, the composer chanced to play his lyricist a couple of other tunes he had lying around. "If you play them for anyone else," warned Mercer, "I'll never talk to you again."

One of the tunes became "Day In, Day Out", recorded thrice by Sinatra in the Fifties in three spectacular and entirely different arrangements by Axel Stordahl, Nelson Riddle and Billy May. The other was "Shangri-La". Oddly, both melodies, although entirely different in character, start on the sixth. No disrespect to any Buddhist monks reading this atop the Himalayas, but an hommage to James Hilton is a complete waste of this music. That opening phrase is so universally touching it has to be a love song.

Mercer gave it a great deal of consideration before he settled on extending Mr Pope's thought:

Fools Rush In

Where angels fear to tread

And so I come to you, my love

My heart above my head...

Many years ago, I saw the great Kenny Everett sing this on his telly sketch show - in close-up, and then on the last line the camera pulled back to show a lifelike human heart bouncing up and down on his hair. It took me awhile to get that image out of my head. But notice how Mercer keeps it so simple, all (save "angels") monosyllables, as if he's afraid of burdening the delicate beauty of the notes. Same in the next section, with only another solitary bisyllable:

Though I see

The danger there

If there's a chance for me

Then I don't care...

This is just such a well-written song. Sinatra's pal Alec Wilder liked to point out the way the melody descends from the G in bar 3 ("tread") to F in bar 5 ("you, my love") to E in bar 7 ("head") to D in bar 9 ("see") to C in bar 11 ("there"). The fool is advancing, step by step, deeper and deeper in until he's face-to-face with the danger there. Except, of course, that Rube Bloom wasn't think of fools rushing in at all, but of Ronald Colman on a mountain-top. So Johnny Mercer somehow managed to fit his scenario to that pre-existing tune absolutely perfectly. And then, as the fool finally throws all caution to the (Himalayan?) wind, the tune likewise rushes up over an octave to top D: "I don't care!"

Just brilliant - and so brilliant that, when it's being sung to you, you don't even notice it.

Mercer finished the lyric, and he and Bloom got the tune to Glenn Miller [and Bob Crosby - SEE BELOW] and Tommy Dorsey - and to Ray Sinatra, Frank's bandleader cousin, whose orchestra recorded it with Tony Martin. They were all eager to get it on wax: Frank was in the studio with Dorsey on March 29th 1940. Ray Eberle and the Miller band followed a day later, on March 30th. And then Tony Martin with Ray Sinatra on March 31st. The Glenn Miller record was released first and was Number One for just one week in July 1940, before being swept aside for a three-month run in the top spot by Sinatra, Dorsey and "I'll Never Smile Again". As for Tony Martin's "Fools Rush In", it entered the Billboard chart for just one week in early August 1940. Two weeks later, Frank's version made its debut. It wasn't as big a hit as "I'll Never Smile Again", mainly because "Smile Again" was still Number One and holding everyone else back. But, if they'd waited for "Smile" to start dropping down the chart, the Dorsey band wouldn't have released anything till the end of the year, and they had so many good records just waiting to be heard.

Whether or not Sinatra remembered his Pope from Demarest High, in early 1940 he was keen to learn. A little Learning is a dang'rous Thing, but Frank was drinking deep. Years later, in an interview with his friend Arlene Francis (of "What's My Line"), he explained:

It's important to know the proper manner in which to breathe at given points in a song, because otherwise what you're saying becomes choppy. For instance, there's a phrase in the song 'Fools Rush In' that says 'Fools rush in where wise men never go but wise men never fall in love so how are they to know?' Now that should be one phrase because it tells the story right there.

But you'll hear somebody say, 'Fools rush in' and breathe, 'where wise men never go' - breath - 'but wise men never fall in love...' But if you do it [in one breath], that's the point - you told the whole story.

It's a shame Sinatra was such a reluctant interviewee because, when you did get him on tape, he was very illuminating. But what a strange choice of song to illustrate his approach to vocal technique. It was four decades after he'd first sung "Fools Rush In" with Dorsey, two decades since he'd last recorded it. Yet it made his point. When you get too "choppy", it's easy to lose "the whole story": The tale is reduced to words set to notes that make a pretty sound. An hour or so before writing this I chanced to hear Susan Boyle sing "Over The Rainbow", and she chops up the phrases entirely randomly, with pauses you could drive a truck through. I don't think she's giving a thought to "the whole story", or even any of it; I'm not sure she's even aware there is one. Yeah, yeah, she's sold a gazillion records, so what do I know? But I doubt she could sell you that song, if you didn't already know it, and didn't already know you liked it.

But that's what Frank had to do on March 29th 1940 with "Fools Rush In": Sell you a song no one had ever heard before - that no one had ever sung before. He couldn't model his vocal on Ray Eberle or Tony Martin because they wouldn't be at the microphone for another 24 and 48 hours respectively. [CORRECTION: Dan Hollombe emails from Los Angeles to point out that Bob Crosby's orchestra did it first - which sent me scurrying to check with the late, great Brian Rust's indispensable reference work, and Mr Hollombe is on the money: Bob Crosby recorded it 11 days before Sinatra, March 18th 1940, with a vocal by Marion Mann (no relation to Michael E of that ilk, I sincerely hope). Which would make Frank the second person and the first male vocalist to record the song. My apologies.]

Only a year separates "Fools" from his first, private, "amateur" recording, "Our Love". But in just a few weeks with Dorsey the new kid had learned a lot:

The thing that influenced me most was the way Tommy played his trombone. He would take a musical phrase and play it all the way through, seemingly without breathing, for eight, ten, maybe 16 bars. How the hell did he do it? I used to sit behind him on the bandstand and watch, trying to see him sneak a breath. But I never saw the bellows move in his back. His jacket didn't even move. I used to edge my chair to the side a little, and peek around to watch him. Finally, after a while, I discovered that he had a 'sneak' pinhole in the corner of his mouth - not an actual pinhole, but a tiny place where he was breathing. In the middle of a phrase, while a tone was still being carried through the trombone, he'd go shhhhh and take a quick breath and play another four bars with that breath. Why couldn't a singer do that, too?

The intimate microphone technique he learned from Crosby, the emotional expressiveness from Billie Holiday, the consonants - those "k"s on "I get a kickkkk out of you" - he picked up from the doyenne of New York cabaret Mabel Mercer ...but Tommy Dorsey was the guy standing in front of him and giving out lessons night after night. That's what he was doing during that recording of "Fools Rush In" - listening to and watching Tommy. Axel Stordahl's arrangement takes it at mid-tempo that gets quite swingy by the end, but it begins with Dorsey on his trombone doing everything Frank described. And, when it comes to the vocal chorus, the boy singer can't match his boss: He still has to take breaths, he can't connect up the lines. But it's close in to the mike, and it has a sweet romantic intensity.

It was all in place by the time he made his second recording (and my personal favorite) of "Fools Rush In" - in 1947, a genuine ballad treatment with Axel Stordahl, and Mitch Miller on oboe, reminding us that, before the idiot novelty songs and Singalongamitchasnoozeroos, there was a sensitive and exceptional musician. For the only time, Sinatra sings the not entirely necessary:

Romance is a game for fools

I used to say

A game I thought I'd never play

Romance is a game for fools

I said and grinned

Then you passed by

And here am I

Throwing caution to the windFools Rush In

Where angels fear to tread...

Tommy Dorsey is five years and a contractual dispute in his past. And yet on this recording Dorsey is present, the smooth seamless legato of his trombone now transferred to his pupil's voice. The end is beautiful, and Sinatra's philosophy on breathing is perfectly suited to what Mercer intended to be a pair of barely perceptible, understated rhymes:

When we met

I felt my life begin

So open up your heart and let

This fool rush in.

The "t" he puts on "heart" is straight out of Mabel Mercer, and would become a Sinatra trademark.

He would record the song once more - in 1960, for the album Nice'n'Easy. The title is a bit of a misnomer: Aside from the eponymous track, the set is poised midway between nice'n'easy and bleak'n'wrist-slashy, as in its predecessor, No One Cares. The eleven ballads are reflective and intimate - many of them written around the same time as "Fools Rush In" and benefiting from a Sinatra mature enough to have lived their lyrics. There are some genuine stand-outs on the album, including "You Go To My Head" and "Try A Little Tenderness". Interestingly, for "Fools Rush In", he declines to follow his own advice and takes a discreet breath in this passage:

Fools Rush In

Where wise men never go

But wise men never fall in love

So how are they to know?

Notwithstanding that breath, Sinatra does all kinds of other things in that passage - dynamics, coloring, emphasis, portamento. In his book Sinatra! The Song Is You, Will Friedwald provides an exhaustive analysis:

He holds the first 'fools' and stretches the 'ooo' sound in the middle, then catches up by fittingly rushing through the word 'rush.' Then he makes it sound as if he's going down a tone on the word 'in' even though both 'rush' and 'in' are actually sung on the same note. The next two lines contain an imitative textual-musical device in which the words 'wise men never' are heard in each, and Sinatra phrases each occurrence of the three words so differently that they might as well be completely different. The first time, he puts a slight syncopation on the word 'never' by accentuating the first syllable ('NE-ver'). The second time, he emphasizes 'WISE men' and then he pauses for roughly half a beat between those two words and the next ('never') so that, rather than stressing the parallel construction of a master lyricist, in this case Johnny Mercer, he makes the lyric seem more immediate, as if it were occurring to him as he's singing it.

That 1960 "Fools" demonstrates another trick he'd learned from Tommy Dorsey 20 years earlier - eliminating the break between the release and the main theme and taking it in one breath:

...then I don't caaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarrrrrrrFools Rush In...

It's a fine arrangement by Nelson Riddle, and the very prominent flautist Harry Klee is one of the best musicians Frank ever worked with. Yet to my ear Mitch Miller's oboe from 13 years earlier is closer to what the song and the singer are trying to say. But the end is beautiful, and Sinatra's philosophy on breathing is perfectly suited to what Mercer intended to be a pair of barely perceptible, understated rhymes:

When we met

I felt my life begin

So open up your heart and let

This fool...

Rush in.

The big voice on "my life begin" and "open up your heart" and then coming back down for a soft, tender, intimate landing on "rush in" is very much a Sinatra specialty: If you're telling "the whole story", a big finish is often less suited than a big pre-finish.

Rube Bloom and Johnny Mercer died within three months of each other in 1976. Sinatra was shocked by Mercer's death and turned his next concert, a few days later in (if memory serves) Palm Springs, into a tribute to his huckleberry friend. Mercer provided Sinatra with a lot of songs that stayed with him all the way to the mid-Nineties: "Summer Wind", "Come Rain Or Come Shine", "One For My Baby"... Rube Bloom, by contrast, wrote a very small number of songs, but, of the few he did, Sinatra made a total of 11 recordings of six of them - not only "Fools Rush In" and "Day In, Day Out", but also "Take Me" (with Dorsey), "Don't Worry 'Bout Me", "Maybe You'll Be There" (in a haunting Gordon Jenkins arrangement) and "Truckin'" (a hit for Fats Waller in the Thirties that Neal Hefti transformed into a killer single "Ev'rybody's Twistin'" thirty years later).

Johnny Mercer liked to say that writing music takes more talent but writing lyrics takes more courage. Which I think is true. "Fools Rush In" is a beautiful but abstract tune, and, when you put words on it, you could easily bury all its tenderness, its romantic generality, in crass specificity - in clodhoppingly awful, mere words. It does take a certain courage, even a mad folly, to do that. But like Alexander Pope and Johnny Mercer said:

Fools Rush In

Where wise men never go

But wise men never fall in love

So how are they to know?

~Mark's acclaimed essay on Johnny Mercer, "Moon River And Me", can be read in his most recent book, The [Un]documented Mark Steyn.

Steyn's original 1998 obituary of Sinatra, "The Voice", appears in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. There's more Sinatra songs in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of all three books are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has launched her own Frank countdown. She has a great Johnny Mercer train song at Number 75, "I Thought About You". Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints is also counting down his Top 100 Sinatra tracks, and he's rocketed up to Number 59, "The Song Is You". And, just in time for Israel's Independence Day later this week, the Evil Blogger Lady has Frank serenading the IDF.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

15) NIGHT AND DAY

16) I WON'T DANCE

17) I'VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN

19) EAST OF THE SUN (AND WEST OF THE MOON)

21) A FOGGY DAY (IN LONDON TOWN)

24) OUR LOVE