Al Pacino turns 75 in a few days' time. He had a great run in the early Seventies - The Godfather, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon - and then made some poor choices. Still, I assumed he'd be one of those Hollywood leading men who aged well and retained their cool. It never occurred to me that he'd decide to spend his late middle-age chewing the furniture and bellowing in ever riper outfits and hairdos. For our Saturday movie date, I was trying to think of the last good Pacino film, and settled on this one - from 1997, Donnie Brasco:

One of the rare endearing qualities about Hollywood execs is their habit, for all their much-vaunted insider cynicism, of reacting to hit films like any old rube at the multiplex. Faced with Four Weddings And A Funeral, instead of saying, "Ah-ha! A skilled director and witty writer have found a way to show off the limited charms of a hitherto undistinguished actor", they decided Hugh Grant was a huge star, showered him with money and his own production company, set up his girlfriend as producer, and then were surprised when he nose-dived into the toilet of history. His Four Weddings director, meanwhile, whom I doubt if one in a hundred of the executive bozos could have named, quietly and unobtrusively come up with a minor gem in Donnie Brasco. It couldn't be more different — one scene alone boasts four killings and a dismemberment — except that, as in Four Weddings, Mike Newell brings a shrewd outsider's eye to bear on a world of elaborate social codes and rituals.

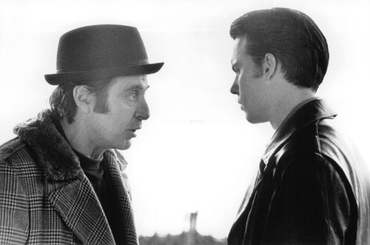

Brasco is a gangster movie, but in a vaguely post-modernish yet just-the-right-side-of-annoying way, both transcends and comments on genre: Al Pacino as Lefty, a sagging minor mafioso, and Johnny Depp as Donnie, the undercover Fed who wins his confidence, are sort of playing at gangsters, trying to be the kind of hoods they've seen in movies. Lefty is punctilious about gangland's courtly etiquette and the proper use of gangster vernacular; Donnie explains in great detail to his FBI colleagues the various meanings with which a hoodlum can imbue the phrase "Fuhgeddaboudit"; on the other hand, Donnie's wife, unaware of what he does for a living, is mystified by the way her college-educated husband is suddenly going around saying "dese" and "doze".

As with the world of Four Weddings, you can't help feeling that the obsession with correct form is merely compensation for the unyielding monotony of their lives. Much of the time, like casual laborers, they're huddling on the sidewalk outside the local underworld hangout, waiting to see if the boss has any work for them. Despite having "clipped" 26 punks in the course of his service to the Family, Pacino's Lefty finds his career stalled at junior-management level and is continually passed over for promotion. His dress sense isn't exactly Reservoir Dogs: his mangy coat and collapsed pork-pie hat accomplish the not inconsiderable feat of giving Al Pacino the forlorn air of Ches in the great British music-hall act Flanagan & Allen (or, worse, Bernie Winters impersonating Ches); told he belonged to a gang, you'd assume it was the Crazy Gang. (Okay, that's enough pop cultural references for centenarian Brits.) Still, there's something rather sweet about the innocent pleasure these New York hoods derive from an assignment to Florida, as they lumber around the hotel tennis-court in outsize floral shirts (this is the 1970s).

On the whole, though, Newell directs against Paul Attanasio's droll script: instead of pointing up the jokes, he down plays them, and the result is a story whose characters derive their pathos from not knowing that how funny they are. The film's stylistic ambiguity complements its moral one: in the inevitable surrogate father/son relationship of Pacino and Depp, the good man has something corrupt and dark in him, the evil man something good. Mafia films are usually stronger on the Family than on the family, but Newell's domestic moments are especially good: the final scene in Lefty's apartment is one of the best things Pacino's ever done. For his part, Donnie, being in deep cover, cannot tell Maggie and the kids what he does or where he is or why he comes home only every few weeks. On one of his surprise visits, the missus drags him off to a counseling session, where his explanation that he's an FBI agent is taken as an especially risible and flippant example of his profound psychological hostility to his marriage.

Maggie, incidentally, is played by Anne Heche, who back then had just acted Demi Moore off the screen (not too difficult, admittedly) in The Juror and was about to be seen as the female lead in Volcano. She was new and spirited, and in this film the camera loves her and her naughty, flashing eyes and wiggly walk. She brings great truth to her role as the put-upon but devoted wife, and I assumed she had a grand career ahead of her. But then she began dating Ellen DeGeneres, and became famous for being a celesbrity instead.

As for Pacino, in the decade that followed he tried to reprise his Hollywood legend-meets-rising youngster shtick to ever more diminishing returns. The absolute nadir was The Recruit (2003), in which the old ham was fully off his meds and roaring to the back of the multiplex as a CIA recruiter mentoring Colin Farrell. The end must rank as one of the worst performances the guy's ever given. Still and all, happy birthday.