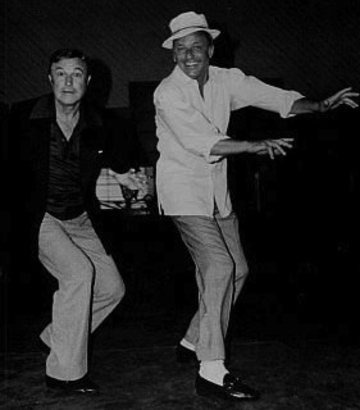

The 1930s were the golden decade of American popular song. The great Broadway blue chips - Cole Porter, Rodgers & Hart - were hitting their stride, and, as we've explored in recent weeks, a whole generation of far lesser known names were providing great individual numbers that, thanks to Sinatra, have lasted across the decades. I mentioned way back at the start of the series that, when Frank was 17, and 18 and 19, it was a very good year, and the songs of his late adolescence and early adulthood would stay with him until the end of his life. This number is typical of many that transcended its era - written for an obscure London show, retooled for Hollywood, and today one of the highest earning songs in Jerome Kern's catalogue, thanks in part to two great Sinatra recordings that introduced the number to Jane Monheit, Michael Bublé, Stacey Kent and many more of today's pop and jazz vocalists. On stage, Frank would occasionally essay a dainty ballerina twirl to start the instrumental break - in defiance of the lyric:

The 1930s were the golden decade of American popular song. The great Broadway blue chips - Cole Porter, Rodgers & Hart - were hitting their stride, and, as we've explored in recent weeks, a whole generation of far lesser known names were providing great individual numbers that, thanks to Sinatra, have lasted across the decades. I mentioned way back at the start of the series that, when Frank was 17, and 18 and 19, it was a very good year, and the songs of his late adolescence and early adulthood would stay with him until the end of his life. This number is typical of many that transcended its era - written for an obscure London show, retooled for Hollywood, and today one of the highest earning songs in Jerome Kern's catalogue, thanks in part to two great Sinatra recordings that introduced the number to Jane Monheit, Michael Bublé, Stacey Kent and many more of today's pop and jazz vocalists. On stage, Frank would occasionally essay a dainty ballerina twirl to start the instrumental break - in defiance of the lyric:

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Madame, with you...

The authors of "I Won't Dance", as sung by Sinatra and everybody else these last 80 years, are Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields. But you'll notice there are various other names attached to it, and therein lies a tale.

In the spring of 1934, Jerome Kern was in London working with Oscar Hammerstein II on a new show called Three Sisters. Nothing to do with Chekhov, except that, like his, the plot concerned a trio of female siblings. In this case, the nub of the story had come to Kern & Hammerstein when they were at Ascot watching the Derby. The three sisters are the daughters of an itinerant photographer who sets up his cart near the races at Epsom Downs: The one daughter dreams of dashing young aristocrats and is determined to marry a peer of the realm; another is smitten by a fairground busker; the third does the sensible thing and settles down with a policeman. You can see where things are headed. Nevertheless, it was Kern & Hammerstein's first truly epic work, sprawling across the decades, since Show Boat seven years earlier, and in telling their tale of "gambling, pre-marital sex, wedding day desertion, concert-party minstrelsy in and out of khaki and the leisure pursuits of the English masses" (as Kern scholar Stephen Banfield synopsizes it) Hammerstein experimented with several devices he would explore more thoroughly a decade later with Richard Rodgers, including a dream ballet. Three Sisters opened at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in April to very mixed reviews. The American authors, sniffed The Daily Herald, "have tried to be terribly English", but unfortunately, according to The Morning Post, "everything rings false." Six weeks later, the show closed, and Jerry Kern, pushing fifty, decided he'd had enough of the uncertainties of the theatrical life. When Hammerstein asked him what his plans were, Kern's reply was terse. "Hollywood," he said. "For good."

Among those who'd seen the show during its brief run was Fred Astaire. He'd been very struck by one song in particular, sung by the great West End star Adele Dixon, as Dorrie (one of the eponymous sisters) to her would-be suitor "Sir John Marsden":

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me to

I'm fond of dancing but I won't dance with you...

In Astaire's line of work, it made sense to be on the look-out for new songs about dancing. When you'd been in the game as long as Fred, you learned to spot an original angle on the subject - and what could be more original than a dance number about refusing to dance? According to Richard Rodgers, Kern had one foot in the old world and one in the new. That's to say, he wrote gorgeous ballads and in his days with P G Wodehouse fun comedy numbers, but he had no great interest in swing, and his occasional forays into more vernacular forms can sound faintly condescending ("Can't Help Lovin' That Man Of Mine" bears the marking "Tempo di blues"). Yet, for a tune by the composer of "Ol' Man River" and "Make Believe", "I Won't Dance" really swings. The form is unusual - perhaps because, as originally conceived for Three Sisters, it was punctuated by ardent musical pleas from Dorrie's putative swain, Sir John. But, for whatever reason, the first section is 12 bars, and the three that follow are 16 apiece. The composer and musicologist Alec Wilder considered the middle section, in contrast to the main theme, "perhaps the most difficult release Kern ever wrote", jumping from C to A flat, D flat and B natural before cleverly working its way back to C. If it weren't for all those key changes, Hammerstein's rhyme scheme would sing very repetitively:

Dancing as an exercise may do good

I've no doubt it's doing quite a few good

Though I know your partners all call you good

For me you're too good

Too good to do good...

Astaire liked it, even in a flop show. In 1934, he and Ginger Rogers were still at the beginning of their screen partnership at RKO. And, as chance would have it, the studio's talented young producer, Pandro Berman, had just bought the film rights to Kern's previous show, Roberta, for Irene Dunne, but with Astaire & Rogers in support. If Three Sisters was a bona fide West End flop, Roberta was a Broadway near-miss. But it had a remarkable score by Kern and Otto Harbach, including "The Touch Of Your Hand", "Yesterdays" (recorded by Sinatra in the Sixties) and "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes". Still, Berman felt the score could use a little punching up, and he looked around for someone to help out. With the exception of Otto Harbach, most of Kern's collaborators in later life tended to be younger men who were a little in awe of the founding father of the American musical. He was so admired by his lyricists that, in a sense, they wrote to him – to his preferred style. Even Johnny Mercer, a master of hipster slang and jive talk and southern charm, chose a more restrained formal voice when he wrote with Kern: "I'm Old Fashioned, "Dearly Beloved", "You Were Never Lovelier".

The exception was Dorothy Fields, who drew out of Kern a quality you don't find in his other collaborations. The daughter of the great vaudevillian Lew Fields (as you can read in Mark Steyn's American Songbook), she was already a potent hitmaker in Tin Pan Alley - the lyricist of "Sunny Side Of The Street", "I Can't Give You Anything But Love, Baby" and many more. "She was a hot property at the time she met Kern," her son David Lahm told me. "Kern was, of course, revered by all of the songwriters, but if we were sitting here in 1934 and we read in Variety that Dorothy Fields was going to work with Jerome Kern, I wonder would we say, 'Boy, what a break for Dorothy Fields' or would we say, 'Boy, what a break for Jerome Kern'."

As it turned out, both. But at first it looked like Miss Fields would be just another scalp for his collection of lyricists. In Hollywood, he refused to ride to the studio in her bright blue car because he thought the color "repulsive". So she had it painted black. On the color of the songs, though, she won out. The Kern tunes most popular today, the ones most performed and recorded, are the songs he wrote with Fields – among them "The Way You Look Tonight", "Pick Yourself Up" and "A Fine Romance", all from their 1936 score for Astaire and Rogers, Swing Time - and all memorably recorded by Sinatra a quarter-century later.

But the partnership began with a couple of interpolations for the film version of Roberta. The original show had been based on a novel called Gowns By Roberta, and Pandro Berman brought Miss Fields on board to come up with a lyric that could function both for a fashion parade and as a genuine love song. She took a 16-bar fragment of music and wrote:

Lovely To Look At

Delightful to know

And heaven to kiss...

Kern didn't hear the finished song until the scene had been shot and he was shown a preview of the picture. But it didn't matter. He liked it, and he liked Dorothy. He was a shortish man, and she was a striking, sharp-witted girl 20 years younger and a good head taller. She called him "Junior", and he didn't seem to mind. And, whether for that or some other reason, the songs with Fields are unlike anything else in the Kern catalogue. "Dorothy dealt well with him," Oscar Hammerstein's son James once said to me. "You had to stand up to him. I don't think you could be a patsy, or Jerry would walk all over you. But if you could make him laugh, you were his friend for life. Dorothy was an extremely outspoken woman. You had to love Dorothy. She said what was on her mind, straight from the shoulder and there was no doubt about it, and she had a pretty wicked wit."

Berman felt the film score could use another number. At that point, Astaire remembered that song he'd liked over in London when he'd swung by Drury Lane and caught Three Sisters. He loved the tune, liked the idea, but thought it could use a more "modern" lyric. Dorothy Fields kept Hammerstein's title and most of the first section:

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me to...

And at that point she junked "Don't ask me to" for "Madame, with you", and thereafter went her own way. Oscar Hammerstein was a sensitive poet and a skilled dramatist, but, when he was called on to kick loose, it could often sound a little stiff. Consider the second section of the original "I Won't Dance":

When your arms

Enfold me

With your arms

You hold me

You hold me

So close and tight

I sort of like it but it gives me a fright

It's never harmed me but who knows when it might?

It's okay, but it doesn't really say anything and it seems - what's the word? - twee-er than the tune is. Miss Fields opted for:

You know what?

You're lovely

And so what?

You're lovely

But oh what

You do to me!

I'm like an ocean wave that's bumped on the shore

I feel so absolutely stumped on the floor...

Those slangy, sassy, teasingly sexual "so whats?" seem to have the measure of the tune in a way that Hammerstein's enfolding arms don't. She does even better on the key-jumping middle section, junking Hammerstein's static "do good"/"few good"/"you good"/"too good"/"do good" rhyme scheme in favor of:

When you dance you're charming and you're gentle

'Specially when you do the Continental

But this feeling isn't purely mental

For Heaven rest us

I'm not asbestos...

"The Continental" is a reference to our Sinatra Century Song #12, but how about the last two lines? "Heaven rest us/I'm not asbestos" is a classic Fields rhyme, and makes "I Won't Dance" the only standard to use the word: In songs of frustrated love, the fire retardants are usually less literal. That's typical of her style – colloquial but literate, unusual but utterly natural. But where did such a startling image come from? Well, as I mentioned above, Roberta is set in the world of haute couture, and one version of the script called for the fashion designer Stephanie (Irene Dunne) to model an incendiary gown called "Armful of Flame". So Miss Fields' first draft of the lyric was addressed as much to the perils of the dress as of dancing:

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Don't ask me

I Won't Dance

Thanks just the same

But I'm not gonna hold an armful of flame...

That's Stephanie modeling her frock, an Armful of Flame.

You got charms

You show them

And what charms!

I know them

I got eyes

But I have learned

What moths that dance with dancing flames all have learned

It's when you dance with dancing flames you get burned...

And that would be Astaire, for who else dances with a flame but a moth?

Dancing as an exercise may do good

And I know your partners all call you good

But for me you're altogether too good

For Heaven rest us

I'm not asbestos

- and you really need to be when you're dancing with an armful of flame:

I want you

To be game

I'll be the same and I'll promise to be tame

But I'm not gonna hold an armful of flame.

Jerome Kern liked that lyric, except in one respect. In the Kern collection in the Library of Congress, you'll find scrawled on the draft in the composer's hand:

If 'Armful of Flame' is the title of one of Stephanie's dress creations, it should also be the title of this number.

The threads on which a hit hangs are very slender. Had "I Won't Dance" been called "Armful Of Flame", it would never have become a standard. It would have been, at best, a cute plot number in the context of the film. You can see, in that draft of the lyric, that Miss Fields is getting there. There's still a bit of Hammerstein, especially in the middle, but there's a lot more brio and vernacular. When the "Armful of Flame" peg went up in flames, she rewrote the lyric unencumbered by plot point - but she kept the asbestos, and it's all the better for just being tossed in, as opposed to being part of some elaborate moth/flame metaphor. Instead, it became a key plank of the real change Dorothy Fields made: Hammerstein's lyric is for someone who won't dance because she's not a very good dancer; Miss Fields' lyric is for someone who won't dance because of what's likely to follow:

I know that music leads the way to romance...

Dorothy Fields took Hammerstein's concept and made it sexy - which is what Sinatra heard in it.

Roberta isn't prime Astaire and Rogers, but the number, simply staged, is pretty good, and Fred's dance to a tune about not dancing is irresistible. And, if it's any consolation to Oscar Hammerstein (who was too professional a writer and too good a friend to Dorothy Fields to nurse any grudges over his discarded lyric), his opening phrase has passed into the language. Oscar the Grouch used it on "Sesame Street" when Prairie Dawn asked everyone to dance: "I won't dance. Don't ask me." The British sitcom "Man About The House" (the forerunner of the American adaptation "Three's Company") used it for an episode in which Robin is obliged to take dancing lessons from Mrs Roper. Newspaper sub-editors find it a useful standby when the feature writer is sent out to trip the light fantastic.

But it works better with the music. And so a song about declining a dance partner became a classic duet, from Fred and Ginger in 1934 to Ella and Louis in the Fifties (a recording that's the very definition of joyousness) and the aforementioned Monheit and Bublé another half-century on. It works as a solo, too - from Peggy Lee to a groovily vocal Woody Herman to Blossom Dearie en français ("Je n'danse pas"). But if I had to single out a couple of sizzling solo version that, in different ways, ring all the juice out the song they'd be Frank Sinatra's two solo recordings.

The first was cut at the end of 1956 to close out A Swingin' Affair - which was basically Son of Songs For Swingin' Lovers. Nelson Riddle's chart is a hard swinger that builds and builds and builds - until Frank is so enthralled he interjects:

You know what?

You're lovely

Ring-a-ding-ding!

You're lovely

And, oh, what you do to me...

There would be a trio of further "Ring-a-ding-ding!" interpolations on record over the years, and eventually an entire Sammy Cahn/Jimmy Van Heusen song dedicated to Frank's catchphrase. But in 1956 it was new, and the interjection was more or less spontaneous, arising from Riddle's wild ride of an arrangement.

Nevertheless, if I had to choose, I'd pick the second of Sinatra's two studio recordings - the one he did six years after Riddle's Swingin' Affair. In 1962, Frank and Count Basie made their first album together, and "I Won't Dance" re-emerged in a terrific slo-cookin' Neil Hefti arrangement Frank kept in his live act almost to the end.

Neal Hefti was never exactly a household name, but he's insinuated his way into the brain of just about everybody on the planet who switched on a TV in the Sixties and Seventies. That's to say, he wrote the supergroovy theme for the film and sitcom spin-off The Odd Couple, and he wrote the ingenious theme for the Batman TV show - the one that spawned a thousand jokes: "How does Alfred call Batman in for dinner?" "Dinner dinner dinner dinner dinner dinner dinner dinner Batman!"

That would be more than enough glory for one lifetime, but Hefti was a multi-talent who did a bunch of other stuff brilliantly, too. He was a marvelous film composer and a terrific arranger who played a critical role in the sound of the Basie band in the Fifties and Sixties. As for singers, he scored just two vocal albums, but they're two of the best in the history of recorded sound: Sinatra/Basie and Sinatra And Swingin' Brass, both from 1962.

"I Won't Dance" is from the Basie set. It wasn't easy to top Nelson Riddle, but I think Hefti did. His arrangement builds beautifully into a sultry groove that climaxes in the instrumental. Basie's band and Sinatra's voice are two very different talents, but on this chart they seem to merge into one, underlined by the way Sinatra lets Basie have the first line of the release before he returns for the closing vocal:

I mean, I like the way you do that Continental...

If I had to sum up the difference between the two arrangements, I'd have to say that Nelson Riddle's sounds like no-way no-how does Frank want to dance, whereas Neal Hefti's makes like he's willing to have you talk him into it.

After two great albums with Sinatra, Hefti evidently figured he could only go downhill, so he quit vocal arranging and, despite innumerable offers from all the best singers right up to his death six years ago, he never returned to it.

At any rate, that's the way he told it. According to others, he quit because Sinatra wouldn't give him equal billing on the Swingin' Brass album. Apparently, the arranger wanted to call it Hefti Meets The Thin One - a rather lame pun on his name, and the fact that young Frankie, way back when in the bobbysoxer days, had been famously emaciated. There was a whole school of singer/arranger albums like that back in the Fifties - Rosemary Clooney records with Nelson Riddle? Hey, why not Rosie Solves The Swingin' Riddle? Still, I can't believe as level-headed a guy as Neal Hefti got so over-invested in a labored contrivance like Hefti Meets The Thin One that he walked out over it. I prefer his reasoning: How could you top those two albums? Best to quit while you're ahead.

Still, while we're quibbling over billing, let's return to that question I posed up top: Why so many names on a song essentially written by one composer and one lyricist? Well, it takes two to tango, but it takes five to say "I won't dance." Jerome Kern is on there because he wrote the music; Dorothy Fields because she wrote the words; Oscar Hammerstein because he came up with the title and the idea; Otto Harbach because he wrote the other lyrics in Roberta; and, finally, Jimmy McHugh because, up to that point, he'd been Miss Fields' exclusive songwriting partner and he felt he was entitled to a piece of the action. Which was a shrewd move. He was a terrific pop composer, but Dorothy Fields was outgrowing him and getting ready to move on. And isn't that what most young ladies mean when they decline a whirl around the floor? Not "I Won't Dance", period, so much as "I'm just waiting for the right partner". Likewise, having spent much of the decade trying to breathe new life into wooden operetta plots, Jerome Kern seemed to be telling the world, "I won't swing, don't ask me." With a zippy new lyricist to twirl him round the floor, this song heralded a reinvigorated Kern adored by Sinatra and Basie and every other swinger:

I Won't Dance!

Why should I?

I Won't Dance!

How could I?

I Won't Dance!

Merci beaucoup

I know that music leads the way to romance

So if I hold you in my arms

I Won't Dance!

Merci beaucoup!

~Mark's original 1998 obituary of Sinatra, "The Voice", appears in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. And Steyn writes more about Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields in his classic book Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, and about "I Won't Dance" and other Fields songs recorded by Sinatra in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

15) NIGHT AND DAY

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has launched her own Sinatra Hot 100, as has Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints. The Pundette is up to Number 82, a great song by a delightful lady Mark knew who led a helluva life, Kay Swift's "Can't We Be Friends?". Bob Belvedere is at hit sound 77, another great song and by one of Mark's compatriots, Ruth Lowe, "I'll Never Smile Again". Sinatra's recording with Tommy Dorsey gave him an early smash in 1940 - and thus the first ever Number One record on America's Billboard pop chart was a Canadian song.