Question: What's the connection between the Muslim call to prayer and Frank Sinatra?

Question: What's the connection between the Muslim call to prayer and Frank Sinatra?

Answer:

Night And Day

You are the one

Only you beneath the moon and under the sun...

Well, that's the way Cole Porter told it, some of the time: His biggest hit was supposedly inspired by hearing the muezzin summon the faithful in Morocco during one of Cole's Mediterranean wanderings. If so, it must rank as Islam's greatest contribution to American popular music (along with "What Is This Thing Called Love?"). Morocco-wise, it seems more attuned to the country's nocturnal near namesake in Manhattan: "The crowds at El Morocco punish the parquet," as Porter wrote on another occasion. Not the Middle East, not the middle west, not the middle anything, but the heights - the height of a particular kind of New York sophistication and elegance: parquet, cocktails, the rustle of gowns... History does not record whether any Moroccan imams were present eighty-two-and-a-third years back to return the favor and hear Broadway summon the faithful to Fred Astaire. But it was on November 29th 1932 at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre that "Night And Day" was formally unveiled to the world.

Wow! Imagine being present that evening and getting in on the ground floor not just of any old hit song but of one of the ten most popular songs of the 20th century! So what did the crowd make of it that first night? As Astaire recalled it, they were a little distracted:

The swells were really out that night, very elegant, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, nothing but white ties, chinchillas, jewels... They were very obnoxious!.. They ran up and down the aisles (talking to each other) - that upset the critics and us on the stage - and it was a little tough to get the plot of the show across.

Oh, well. The plot of The Gay Divorce was about the guy (Fred) loving the gal (Claire Luce), but she thinks he's the professional co-respondent in her divorce case. And, if you're wondering what a "professional co-respondent" is, that just proves that not everything about The Gay Divorce holds up as well as "Night And Day". But when Astaire started to sing, even the chinchillas ceased their infernal din:

Like the beat beat beat of the tom-tom

When the jungle shadows fall

Like the tick tick tock of the stately clock

As it stands against the wall...

And when Fred and Claire Luce finished dancing dreamily over the furniture, the first-nighters erupted. Leo Reisman, Eddie Duchin and Astaire himself had hit records of "Night And Day" within a few weeks; it was a top sheet-music seller by January of 1933 ...and it never stopped, through Billie Holiday, Django Reinhardt and Stan Getz to the Temptations, Chicago, Everything But The Girl, U2 and Rod Stewart. It's a song that seemed tailored for the performer and the moment - a distillation of a particular kind of uptown elegance and sophistication - although, judging from U2's fabulously bombastic take, that's not what Bono heard in it 60 years later. Sinatra alone recorded the song a gazillion different ways: As a dreamy ballad in the bobbysoxer Forties. As a ring-a-ding-dinger in the swingin' Fifties. He did it big and stately and formal with an army of strings. He did it with Latin bongos. He did it as a kick-around jump tune with trios and quartets. He sang it variously with the intro verse at the intro, and with the intro verse in the middle, and with the intro verse booted outro entirely. And, having exhausted all other options, in 1977 he did it as a disco number. The song stayed with him every which way for over half a century, and he never tired of it in all those years.

Which is very different from the autumn of 1932, when a lot of key Cole Porter associates tired of "Night And Day" within 16 bars. His publisher Max Dreyfus heard the bass notes under the first line of the verse and decided the song would never catch on. His buddy Monty Woolley stuck with it to the chorus and then told Cole, "'I don't know what you're trying to do, but whatever it is, throw it away. It's terrible." The show's co-producer, Tom Weatherly, didn't care for it. And neither did Fred Astaire, who'd signed on to The Gay Divorce after Porter played him the show's "other" ballad, "After You, Who?", but objected to "Night And Day" and demanded it be dropped.

Cole, normally so accommodating of star whims, put his foot down: Aside from being inspired by the Muslim call to prayer, the song had also been crafted for Astaire's voice, and range. Actually, "range" may be overstating things. The beginning of the song ranges from G to G. G after G after G, for 35 notes in a row:

Like the beat beat beat of the tom-tom

When the jungle shadows fall

Like the tick tick tock of the stately clock

As it stands against the wall...

Obviously, the tune is taking its cue from the lyric, and very effectively. After the beat-beat-beat and the tick-tick-tock, Porter takes it up just half a tone for the drip-drip-drip:

Like the drip drip drip of the raindrops

When the summer show'r is through...

That bit's nothing to do with the muezzin calling the faithful but rather with Mrs Vincent Astor complaining about a post-rainstorm aural distraction at a luncheon party at Newport, Rhode Island: "That drip-drip-drip is driving me mad," she snapped. Porter was struck by the thought, and extended it: The drip-drip-drip and the beat-beat-beat and the tick-tick-tock are driving me mad. Why?

So a voice within me

Keeps repeating

You - you - you...Night And Day

You are the one...

The verse is unrelenting because, as Porter (played by Kevin Kline) says in the 2004 biopic De-Lovely!, it's about obsession. Porter thought the audience would hear that, even if Max Dreyfus and Monty Woolley and Fred Astaire couldn't. Having moved off G, the chorus doesn't go too far, moving up a minor third rather than a fourth for the release, and staying in mid-range in order not to discombobulate a star who had to save his energies for leaping and twirling around the stage. Still, Astaire was troubled by the title phrase:

Whether near to me or far

It's no matter, darling, where you are

I think of yoooooo

Night And Daaaay…

Earlier Astaire songs such as "Fascinating Rhythm" had never required Fred to hold notes. He was worried that his voice might crack. And, while he appreciated the comfortable range of most of the song, he didn't care for the big finish and its octave rise:

And its torment won't be through

Till you let me spend my life making love to you

Day and night

Night And Daaay!

Astaire thought the end would be torment, and he'd be the one who was through. He was wrong.

With his sister Adele, Fred had been one of the top Broadway acts of the Twenties and had introduced a lot of big numbers by the Gershwins and others without ever acquiring any reputation as a singer. Porter gave him a song that would change that, and establish Astaire's solo persona: not just the greatest dancer of stage and screen but a vocalist, too. If Sinatra is the singer who planted more songs in the standard repertoire than anyone else, then Astaire can claim to be the singer who introduced more of those songs than anybody else. Romantic ballads, love songs, charm songs - "Cheek To Cheek", "Dancing In The Dark", "The Way You Look Tonight"...

It wasn't Astaire or Sinatra or any other singer who got me thinking about "Night And Day", but Ring Lardner, the great sports writer and satirist. As a teenager, I loved reading Lardner because of his ear for American English. I subsequently discovered he was a frustrated songwriter, in which field he never quite understood the relationship between music and vernacular speech. Years ago I adapted some of Lardner's short stories and other writings about Broadway and Tin Pan Alley for a BBC production with Stubby Kaye, and while working on it I found myself sifting through Lardner's short-lived column for The New Yorker on "radio music". One week, he wrote as follows:

With 'Night And Day' Mr Porter makes a monkey out of his contemporaries and he does it with one couplet -

'Night And Day under the hide of me

There's an oh, such a hungry yearning burning inside of me…'

Lardner was mocking Porter for the inverted word order of "the hide of me". "Perhaps it's carping," writes the musicologist Stephen Citron, "but the phrase... inserted obviously to rhyme with 'inside of me' strikes me as unworthy of the man who could write such an insouciant inner rhyme as 'there's an, oh, such a hungry yearning burning...' in the very next line." As it happens, Lardner didn't care for the "oh, such a" business either, and merrily offered his own variations on the theme:

Night And Day under the bark of me

There's an oh, such a mob of microbes making a park of me…

And:

Night And Day under the fleece of me

There's an oh, such a flaming furneth burneth the grease of me...

You can see his point. Nobody says "the hide of me", not even as an "obvious" rhyme for "inside of me", which itself is barely any closer to real English: Why not "inside me"? But that's why Lardner wrote short stories and Porter wrote songs. A lyric is not merely a matter of the right words, but the right words for those notes, and, when the music demanded it, Cole was unashamed to be ardent. I had a few conversations with Alan Jay Lerner, author of Camelot and My Fair Lady, about Porter, and the word Lerner always used was "passion". Nobody would ever describe Ira Gershwin or Irving Berlin as a "passionate" writer, but Porter was, and when he had the melodic and harmonic end working overtime he let the lyric verbalize them. The romantic obsession of "Night And Day" exists in a heightened reality. To get hung up on an inverted word order that would sound silly in a Ring Lardner baseball story is to miss the point.

Porter was also sufficiently deferential to his passion to let it dictate the form of the song. As Stephen Citron notes, most composers and lyricists use the middle section - the bridge, the release - as an exercise in contrast: The main theme of, say, "The Tender Trap" is very rhythmic - "You see a pair of laughing eyes..." - so the middle section is broad and legato - "Some starry night..." The main theme of "The Lady Is A Tramp" is about stuff she doesn't dig - "She gets too hungry for dinner at eight..." - so the release is about what she likes - "She loves the free fresh wind in her hair..." Yet Porter is an exception to the rule. His releases aren't contrasts, but intensifications. "Night And Day" isn't a conventional 32-bar song. It's 48 measures divided into two long opening sections followed by a short bridge and a truncated reprise of the main material, but it works because it builds and builds:

Day and night

Why is it so?

That this longing for you follows wherever I go

In the roaring traffic's boom

In the silence of my lonely room

I think of you

Night And Day ...

Isn't that "roaring traffic"/"lonely room" couplet marvelous? One of the best in the catalogue. But then he ratchets it up a notch. The release is almost a literal release, one great howl of passion:

Night And Day

Under the hide of me

There's an oh, such a hungry yearning burning inside of me...

Honestly, what words would you rather have there? The hunger and the yearning and the burning is palpable. And then Porter wraps it up with:

And its torment won't be through...

Till when exactly?

Till you let me spend my life making love to you...

Which sounds like a whole bunch of other torment for whoever's on the receiving end. I think the trick is not to make too much of a meal of all the passion. It's there, written into the music and the lyric; there's no need to labor it. The first time I heard Steve Lawrence's Latin-lounge arrangement of the verse, I thought it was the cheesiest thing you could do to the song. But after years of hearing tremulous overwrought chantoosies banging away at it, I kinda feel Steve's on to something: There's more than one way to obsess. Likewise, at the other end of the song, I always liked catching Sinatra in concert just to hear him freewheel through the second chorus: "And this torment won't be through/Till you let me spend my life jumping on you/Day and night, Night And Day..." Which, to be honest, sounds less burdensome to the other party than the original lyric.

By that stage, he preferred to do it just with his rhythm section and kick loose a little. "Night And Day" is one of those tunes that's melodically simple (all those repeated notes) but harmonically complex, and Sinatra had a jazz improvisor's appreciation of harmony. He called the song one of the greatest of the last hundred years, and his relationship with it went back to the very beginnings of his career, a year or two after Astaire introduced it in The Gay Divorce. "It's one of the first songs I sang when I was a young, rising singer," he told Sidney Zion. "I was using 'Night And Day' a lot wherever I worked."

In 1937-38, he was working at the Rustic Cabin, a roadhouse near Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, where on Sunday evenings Manhattanites heading back from the country would, as Frank put it, "stop and have a little nip before they went over the bridge to go back to New York". One night, when "there were about seven people in the audience and we had a six-piece orchestra", the trumpeter Johnny Bucini nudged Sinatra and said, "Do you see who's sitting out there?"

It was Cole Porter, en route back to the city. Frank whispered to the bandleader, "Let's do 'Night And Day' for him." So he stepped forward and said:

Ladies and gentlemen, I'd like to sing this song and dedicate it to the greatly talented man who composed it and who may be one of the best contributors to American music..

He invited Mr Porter to stand up and take a bow. Then the band struck up, and Frank sang:

Night And Day

You are the one...

At which point he forgot all the words - and spent the rest of the song singing "Night And Day/Day and night" over and over and over.

Years later, as a bestselling singer and big movie star, he was re-introduced to Cole Porter, who immediately said, "I don't know if you remember an evening with me at some nightclub where you worked..." In fact, they became fast friends, and in his final years, as the pain-wracked Porter retreated further into social isolation, Sinatra was one of the last dinner companions whose company he still enjoyed. (It was Cole who suggested to Frank he sing "It's All Right With Me" as a ballad in the 1960 film of Can-Can.)

Whatever the defects of that first performance for Mr Porter, Frank made up for it in the ensuing half-century. In 1942, it was one of the songs he sang on his first ever session as a solo singer (along with "The Song Is You"). He recorded it again eight months later for the film Reveille With Beverly. Certain Sinatra amendments were already in place - extending the lyric to "way down inside of me" and stepping up the scale on the extra words - and those Frankisms would stay with him into the disco era. For much of the 1940s it was the intro theme on his radio show, Old Gold Presents Songs By Sinatra. Throughout this period he used essentially the original 1942 arrangement by Axel Stordahl, although the sweetly innocent legato vocal evolved. Most people think of the Stordahl arrangement as a "ballad" and the 1956 Nelson Riddle version as a "swinger", but in terms of overall speed there's less difference than you might think. The real ballad treatment, with the verse at crawl tempo, had to wait till Don Costa's chart for the 1961 Sinatra & Strings - but I think I prefer the stripped-down version, with just Frank and guitarist Al Viola, from his 1962 world tour.

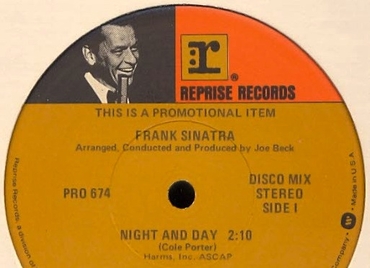

As for the 1977 disco version ...oh, dear. Having made a Seventies disco megamix of my own, ahem, signature song, I'm hardly in a position to object in principle. There's certainly a great disco mix to be wrung out of "Night And Day", but Joe Beck's arrangement is so third-rate and half-hearted. Frank's drummer, Irv Cotler, hated it; and so did his conductor, Vinnie Falcone. One day, at the tail-end of the disco era, they were rehearsing at Caesar's Palace. "We were doing the thing," Falcone told Will Friedwald, "and I made some kind of face, and he stopped the band. He said 'Throw it on the floor!' And we never did those disco things again. We got the old 'Night And Day' back out!"

Frank kept his word: He spent his life jumpin' on "Night And Day", day and night.

But, ballad or disco, loungey or folky, jazz or rock, singers and instrumentalists agree this is one of those songs whose torment won't ever be through. It's a basic text of the American canon, whose power even Hollywood understood. When they filmed The Gay Divorce two years later in 1934, they changed the title at the censor's behest to The Gay Divorcée (on the grounds that, while no divorce could ever be gay and bright and delightful, one of the partners to it could conceivably be), but they also junked the entire Porter score as "too New York". Except, that is, for "Night And Day".

Porter may have been "too New York", but "Night And Day" played from coast to coast and made its author America's second highest earning songwriter. For the rest of his life, it was the song the band played when Porter walked into a nightclub or a restaurant, anywhere in the world. When he visited Zanzibar, the Sultan played it for him. "Too New York", but just Zanzibar enough. Maybe it was the Muslim thing. Or maybe it was Mrs Astor. Or maybe, when it comes to that "sly biological urge", as Noel Coward wrote in another context, "it really was Cole who contrived to make the whole thing merge". He had a set of cufflinks made: The moon on one wrist, the sun on the other. Night and day, get it?

Night and day, 24/7, on and on, for eight-and-a-third decades and on to the centennial, in the roaring traffic's boom under the disco glitterball and the silence of my lonely room with just acoustic guitar accompaniment:

I think of you

Night And Day.

~Mark's original 1998 obituary of Sinatra, "The Voice", appears in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. And Steyn writes about Cole Porter in his classic book Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, and about Sinatra's famous record of Porter's song "I've Got You Under My Skin" in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

6) THE ONE I LOVE (BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE)

8) STARDUST

10) WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE?

11) CHICAGO

12) THE CONTINENTAL

13) ALL OF ME

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has launched her own Sinatra Hot 100, as has Bob Belvedere over at The Camp Of The Saints. The Pundette is up to Number 83, a song co-written by Harold Arlen's close friend and occasional lyricist Ira Gershwin, "Embraceable You". She includes versions by young Frank and middle-aged Frank, but not the lovely take he did in the Nineties with Lena Horne, full of autumnal tenderness, and one of the better things to come out of the Duets project.

Aside from his official countdown, Bob Belvedere has now started a rundown of "honorable mentions", songs bubbling under his Hot 100 - and three of the four on this list are absolutely top-notch.