The self-glorying fantasies of NBC News "managing editor" Brian Williams multiply with every passing day, most recently and risibly his boast that he looked down the very tube of the RPG launcher that shot down the chopper in front - which is quite an accomplishment at that altitude - and the evolving numbers of three-week-old puppies he's rescued from blazing buildings. So I thought it would be appropriate for our Saturday movie date to pick another tale of journalistic fabulism - Billy Ray's 2003 biopic of a New Republic fantasist, Shattered Glass:

I can remember the exact moment when I stopped reading Stephen Glass and, for the most part, The New Republic. It was June 1997 and he'd been given the cover story — "Peddling Poppy", about the ongoing attempt to rehabilitate the first President Bush. About half-a- dozen paragraphs in, Glass wrote:

Another good place at which to contemplate what is going on with Bush is the First Church of George Herbert Walker Christ, which is a circuit church run by a handful of evangelicals who hold that Bush is the reincarnation of Christ... Members wander from city to city holding services in public parks and civic halls and handing out leaflets on street corners. Inside the leaflets is a complicated genealogical web that purports to show that Bush is descended directly from the Messiah. The web is written in minuscule print with dozens of winding lines extending like varicose veins from circles within circles. The circles represent secret love children...

Yes, well. It could be, I suppose. But then Glass went on:

Like many fringe religions, the First Church of George Herbert Walker Christ is extremely regimented. Members adhere to strict dietary laws similar to Jewish kosher rules, hut include other Bush-specific prohibitions, including one against broccoli.

At that point, I threw the magazine across the room and never read another Stephen Glass article. Bush, you'll recall, had sparked controversy — at least among those in the broccoli business — when he said he couldn't stand the vegetable. But making it a dietary stricture for a Bush church was too neat a jest. If there was a real Bush church, it would take itself too seriously to riff off his broccoli gag. So that meant, I figured, that this First Church of George Herbert Walker Christ must be some self-consciously wacky group of tedious self-promoting jokers like Britain's Monster Raving Loony Party, and Glass and his editors were trying to pass it off as a genuine phenomenon.

Instead, as was eventually revealed, Glass had made the whole thing up, and his editors had swallowed it, broccoli and all. A year later, halfway down the all-time great corrections column, wherein The New Republic announced the preliminary results of its exhaustive investigation into nearly 30 bogus stories Glass had written for them, there appeared this note:

In 'Peddling Poppy', Glass's account of a Hofstra University conference on the Bush presidency, 'The First Church of George Herbert Walker Christ', 'Mary Ung' of the 'Committee for the Former President's Integrity', and 'a small skydiving industry newsletter' called Jump Now are invented.

You don't say. American magazines are notorious for their fact-checkers, but Glass's stories are fake at a more basic level than dates, names, places: they don't pass the smell test. Within his two-year meteoric rise and fall, certain themes recur: a church for George Bush, a shrine to Alan Greenspan, a woman who worships former presidential candidate Paul Tsongas... All false.

And yet The New Republic got suckered by them every time. You can see why in Billy Ray's Shattered Glass. The high point of Glass's life is not the published story but the editorial meeting at which he pitches his latest ideas. "Where does he find these people?" marvels one adoring colleague. "Unbelievable!" says another. They're stories about young conservative activists, Christian talk radio, areas of life that are as remote and exotic to his fellow journalists as any tribe in New Guinea. But, happily, Glass's too-good-to-be-true anecdotes confirm their general worldview — young Republicans are drunken bullies, evangelicals are dopes and pushovers, etc. "You have to know who you're writing for," says Glass, and he does. Or as John Pilger remarked a few years later, apropos the London Daily Mirror's fake army torture pics from Iraq, "They may not be true. But what they represent is true." In other words, it's true because it fits my prejudices. Glass fit the prejudices of The New Republic, Harper's, George, Rolling Stone, and played smoothly on the reflexive condescension so much of the media have for so many of the American people.

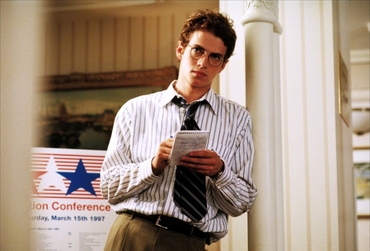

But, of course, you can't make a film like that about American journalism. In most movies about a cocky young faker on the make — Catch Me If You Can, The Talented Mr Ripley — it's the phony gets glamorized. Not here. Instead, it's the profession he has the impertinence to sully that gets imbued with a reverence that would strike any Fleet Street hack as hilarious. Hayden Christensen plays Glass as a puppyish nerd in over-large specs. He appears about 25 when the picture starts and seems to lose a couple of years every ten minutes. By the end, he looks like Harry Potter all out of tricks.

But, when you're up against a sociopathic schoolboy like Glass, you need a hero. And slowly a film about Glass turns into a film about his editor, Charles Lane (Peter Sarsgaard), and his dogged determination to crack the case piece by painstaking piece. Imagine All The President's Men with Woodward investigating Bernstein and you'll get the general idea. Towards the end, there's a moment when Lane gets a vital piece of info and the final piece of the puzzle clicks into place, and you'd think you were watching Miss Marple.

The overwrought pun in the title, Shattered Glass, captures the tone of the picture. Glass has never seemed in the least bit shattered, but America's media ethics bores reckon they ought to feel shattered on his behalf. So Billy Ray frames the picture with a trip by Glass back to his old school to visit a class full of adoring journalism students — although this too proves to be another Glassy-eyed fantasy. And whole media self-affirmation exercise comes together in a maudlin climax in which we see the class applauding Glass for his statement of journalistic principles while simultaneously the staff of the New Republic applaud Lane for his robust defence of those principles, the two scenes being accompanied by Mychael Danna with the kind of weepy musical wallpaper that would seem excessive in a chick-flick deathbed-reunion scene. Somewhere in heaven, Hecht and MacArthur, authors of The Front Page, must be laughing their heads off. Stephen Glass and Jayson Blair didn't kill American journalism. But the absurd self-aggrandizement of journalism represented by the Charles Lane figure is a big part of the narcissistic culture that lures a competent well-coiffed teleprompter reader down the path to fake war stories.