Frank Sinatra's last studio solo album was recorded in 1984. Thereafter, there would only be live albums and celebrity duets. By comparison with its predecessor, She Shot Me Down, an album of dark, largely unknown saloon songs, LA Is My Lady has a loose, relaxed vibe to it, as if everyone involved went into the studio, had a good time, and let the chips fall where they may. Quincy Jones and Sinatra had been working on a project with Lena Horne, which, as was the way with Q, had expanded and expanded to incorporate more and more of Jones' Rolodex - Lionel Ritchie, Barry Manilow, Michael Jackson. And, when it all collapsed under the weight of its over-expansion, FS and Q figured, hey, let's just go into the studio and make a jazzy little record - in fact, the jazziest Sinatra album since his work with Count Basie in the Sixties. Jones conducted a band of all-star soloists, cutting loose on a few new songs but mostly familiar standards. And the oldest song on the album was almost as old as the singer:

Frank Sinatra's last studio solo album was recorded in 1984. Thereafter, there would only be live albums and celebrity duets. By comparison with its predecessor, She Shot Me Down, an album of dark, largely unknown saloon songs, LA Is My Lady has a loose, relaxed vibe to it, as if everyone involved went into the studio, had a good time, and let the chips fall where they may. Quincy Jones and Sinatra had been working on a project with Lena Horne, which, as was the way with Q, had expanded and expanded to incorporate more and more of Jones' Rolodex - Lionel Ritchie, Barry Manilow, Michael Jackson. And, when it all collapsed under the weight of its over-expansion, FS and Q figured, hey, let's just go into the studio and make a jazzy little record - in fact, the jazziest Sinatra album since his work with Count Basie in the Sixties. Jones conducted a band of all-star soloists, cutting loose on a few new songs but mostly familiar standards. And the oldest song on the album was almost as old as the singer:

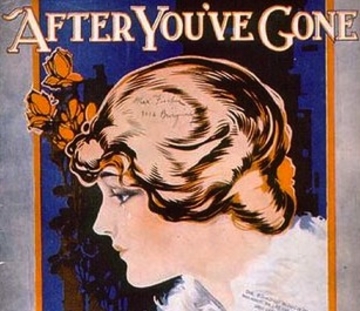

After You've Gone

And left me crying

After You're Gone

There's no denying

You'll feel blue, you'll feel sad

You'll miss the dearest pal you ever had…

"After You've Gone" was born in 1918, just three years after Sinatra. There aren't a lot of pre-1920 songs that are still regularly performed and recorded, and most of those that are live on mainly as instrumentals – "St Louis Blues", for example. But "After You've Gone" is a rare exception. Al Jolson introduced it at the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway, and the world has kept singing it for almost a century: Sophie Tucker, Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Frankie Laine, Bobby Darin, Nina Simone, Loudon Wainwright III, Phil Collins, Suzy Bogguss, Jamie Cullum, Fiona Apple, Hugh Laurie…

But the very first record of "After You've Gone" was made on July 22nd 1918 in Camden (down the other end of New Jersey from Hoboken) by Marion Harris, with Rosario Bourdon's orchestra. Compared with later recordings, Miss Harris took it at crawl tempo - 80 beats per minute - as befits the ostensibly gloomy scenario of the text. And then everyone seemed to agree that there was no point letting the lyric hold the tune back, and the song spent the rest of the century getting faster and faster.

I don't suppose baby Frankie was paying much attention to such things at the age of two-and-a-half, but the song would certainly have been in the air in those early childhood years. Aside from Miss Harris, Henry Burr & Albert Campbell and Billy Murray & Gladys Rice made somewhat stiff records of it, and it was played with rather more abandon from palm courts to speakeasies to burlesque houses. I would imagine that young Frank knew every word by the time he was ten.

It was written by the songwriting team of Turner Layton and Henry Creamer. Layton, the music half, was born in Washington, DC in 1894, the son of a music professor and a teacher. Creamer, the words man, was 15 years older, born in Richmond, Virginia in 1879. Both men were black, and they enjoyed huge success in the American music biz almost a century ago, at a time when the contemporary grievance industry would have us believe such a thing wasn't possible. But they met up sometime in the second decade of the 20th century and by 1917 were writing songs for the Ziegfeld Follies. Creamer was a multi-talent: lyricist, singer, dancer, actor, director, producer, impresario. He was no Ziegfeld, but his Creole Production Company brought Strut, Miss Lizzie to Broadway in 1921, and made Layton and Creamer's title song a hit. That was Layton's principal interest in the partnership: hit songs. The following year the team hit it big with "Way Down Yonder In New Orleans", which the sheet music advertised as "A Southern Song, without a Mammy, a Mule, or a Moon", in mockery of the Tin Pan Alley clichés of the moment. "Way Down Yonder" transcended such passing fancies, and survived long enough to be a rock'n'roll hit for Freddy Cannon and a surf song for Jan & Dean at the dawn of the Sixties, and a showstopper for Harry Connick Jr at the Hurricane Katrina fundraiser in 2005.

Layton & Creamer went their separate ways in 1924. Henry Creamer found a new writing partner in James P Johnson and had a hit with "If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight", and died in 1930. Turner Layton sailed to England, and became a huge success in the British Isles as one half of Layton & Johnstone, a double-act that in the course of a decade sold ten million records. After Tandy Johnstone was named in a divorce action and returned to New York, Layton struck out on his own and was an elegant cabaret fixture at the Café de Paris in London until after the Second World War. When he died in 1978, many Britons never knew that the popular 'tween-wars performer had had an earlier life as a songwriter and written "After You've Gone". Likewise, many African-Americans never knew that a pioneer black songwriter had had a second life on the other side of the Atlantic as a London cabaret darling.

There are no and-then-I-wrote stories about "After You've Gone". It just emerged into the world, fully formed and "as American as a song can get," as musicologist and Sinatra pal Alec Wilder put it. The chorus is only 20 bars, but so what? The 32-bar standard was not yet chiseled in granite in 1918, and the American popular song was in transition, gradually casting off the verse-and-chorus format with the chorus relegated almost to a 16-bar afterthought. Layton and Creamer's chorus may be only 20 bars but it's no afterthought.

It's a nervy, jumpy melody of short ascending phrases with at least one chord change every bar. It starts on the sub-dominant, and seems to come flying out of the gate with a momentum few other songs can match. It says everything it needs to say in a quartet of four-bar sections plus a four-bar tag. Who needs 32 bars? But, if you want anything else, there's nothing but one of those and-that's-why-I-sing explanatory verses set to a rather pedestrian tune:

How could you tell me that you're goin' away?

Which is a bit whiny, and it doesn't get any better from there:

Oh, honey baby, can't you see my tears?

Listen while I say:After You've Gone

And left me crying…

Who needs it? Mildred Bailey liked to sing the verse of "After You've Gone", but most other singers figure they can live without it. Shorn of their verse, those 20 bars became one of the most valuable copyrights in popular music over the next two-thirds of a century.

So, on hearing in 1984 that Sinatra's planning to record "After You've Gone", your initial reaction would be: Surely he must have done the song before, sometime in the last 60 years… If so, no evidence survives. Tommy Dorsey had it in his book, but he doesn't seem to have let his boy vocalist anywhere near the song. On the radio with the Dorsey band on Sunday June 7th 1942, "After You've Gone" was included in a medley with "My Silent Love" and "I'll See You In My Dreams". But Jo Stafford got "After You've Gone", and Dorsey saved "See You In My Dreams" (whose opening bars have a similar chord progression to "After") for his trombone, leaving Sinatra with "My Silent Love".

Forty-two years later, sans GI Jo and "the Old Man" (as they called Dorsey), sans "My Silent Love" and "I'll See You In My Dreams", Sinatra finally had "After You've Gone" all to himself. He was running low on trusted collaborators by 1984 – one long-time arranger, Don Costa, had had a fatal heart attack the year before at the age of 57, and another, Gordon Jenkins, was dying of Lou Gehrig's disease. As for Nelson Riddle, he was off with Linda Ronstadt. And Quincy Jones, who was producing the LA Is My Lady album, had just come off producing the biggest-selling album of all time – Michael Jackson's Thriller – and was far too grand to do any orchestrating. So Sinatra found himself in the studio with a bunch of charts by seasoned arrangers who were nevertheless not his "house arrangers" and wrote from a little ways outside the Sinatra style – Frank Foster, Sam Nestico, Torrie Zito... The result are charts with a jazzy looseness, certainly when compared with the polish of Riddle, but that suit the singer's sexagenarian chops. Saxophonist Frank Foster's arrangement of "Mack The Knife" would stay in Sinatra's act right until the end, but his take on "After You've Gone" is just as impressive. "There were no other charts in the whole production that were quite like that," Foster told the musicologist Will Friedwald. "I was just trying to put a heavy personal Frank Foster touch on it. I try not to borrow from anybody else. I just went down into my own arsenal of licks and said, 'I'm just going to make this a bad mother**ker!' I liked the challenge of writing the uptempo arrangement."

Tempo-wise, it isn't the fastest that "After You've Gone" has gone, but from George Benson's opening guitar licks it's rhythmically busy and, especially in the instrumental passages, appears to propel itself at breakneck speed. The solos are generally longer on this album, and Sinatra's more than happy to let Benson and then Lionel Hampton on vibes take all the bars they want. Hampton's history with "After You've Gone" went back half-a-century to his own 1937 recording. The band is, as Hamp might put it, flying home, but, at that clip, those 20 bars come round again awful quickly, so Foster decided to provide Sinatra with the second chorus that Henry Creamer never got around to writing back in 1918:

After we paid

Our dues together

You should have stayed

Through all that nasty weather…

In a sense, Foster makes explicit what the tune always implied. The guy may be singing about how you've left him cryin' and broken up, but, after you've gone, he's gonna be back out there on the scene, and you'll get yours:

There'll come a time

Now don't forget it

There'll come a time

When you'll regret it...

And so, for the reprise, instead of missing your "dearest pal", Frank brags:

You'll miss the slickest partner you ever had...

I especially like Foster's rewrite of the tag. Instead of…

After You've Gone

After You've Gone away

…Sinatra sings:

After you've split

After you've flown the coop!

Which is very sly on Foster's part – because it's written in perfect Sinatra argot and surely came from nights on the stand listening to Frank's spoken introduction to "One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)": "This simply tells the story of a guy whose chick split. She flew the coop…"

The difference this time is that when Sinatra sings those words they kick into a killer instrumental that really does fly the coop.

Sinatra sang most of the best standards of the 20th century, but we all have a list of songs we wish he'd got to. That's the service LA Is My Lady provides: He got to one last handful of them just in time, and he did them great credit. But Frank, George Benson, Lionel Hampton, Frank Foster and Quincy Jones are on especially good form on "After You've Gone".

Neither Turner Layton nor Henry Creamer heard that record. It came long after Creamer was gone – 54 years. But, in his second life as a West End song stylist, Layton lived until 1978. When his daughter died in London in 2001, she left her dad's copyrights to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, the same hospital to which J M Barrie bequeathed his Peter Pan royalties. Which goes to show that, pace Shakespeare, the good that men do can live on after you've flown the coop.

~Mark's original 1998 obituary of Sinatra, "The Voice", appears in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. You can read about composer Jule Styne and the creation of some classic Sinatra songs in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

SINATRA CENTURY

at SteynOnline

~For an alternative Sinatra Hot 100, the Pundette has launched a dedicated Sinatra Centenary site, counting down from Number 100 to Number One. This week she's got to Number 96 - "I Could Have Told You". You can hear Sinatra singing "I Could Have Told You" on the SteynOnline centenary celebration of songwriter Carl Sigman. Mr Sigman is the lyricist of what we like to think of as Mark's signature song.